The popular fruit and vegetable stand at LJB Farms was once just

a youthful pastime for Russ and Brent Bonino. Instead of lemonade,

the preschool-aged brothers hawked pears off their parents’ farm

from an impromptu table of plywood and sawhorses.

The popular fruit and vegetable stand at LJB Farms was once just a youthful pastime for Russ and Brent Bonino. Instead of lemonade, the preschool-aged brothers hawked pears off their parents’ farm from an impromptu table of plywood and sawhorses.

Today, that once-humble operation has evolved into a cornerstone of the Bonino family’s 85-year-old agriculture business – and also the focus of Russ and Brent’s individual careers. Both work side-by-side with their parents Louis and Judy Bonino on the family’s Gilroy and San Martin ranches.

Meanwhile, a few miles north in Morgan Hill, the Chiala brothers also work hand-in-hand with their mom and dad to tend the family’s 350 acres of farmland and food processing business.

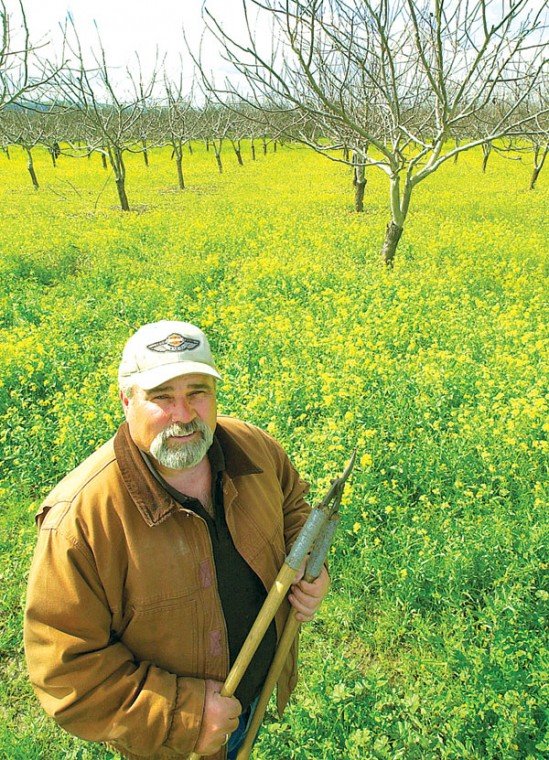

And in the picturesque San Juan Valley, Anthony Freitas is carrying on a family tradition as well. Fulfilling a promise he made to his dying father, he tends a stand of apple and walnut trees that are some of the few remaining from the days when the orchards of his brethren and neighbors spread across the area.

Although the acres of nature’s bounty once so prevalent here have been largely replaced by acres of cubicles, the family farming tradition is still alive south of San Jose.

The Bonino, Chiala and Freitas operations are some of several farms where two or more generations work or have worked side-by-side and proudly carried on family traditions – although the nature of those traditions are changing and maintaining them isn’t necessarily getting any easier.

Thirty-two-year-old Russ Bonino knew agriculture was on his horizon ever since those childhood days selling pears and accompanying his father around the family ranches.

“I liked it,” he said. “I like being outside – I’m an outside person.”

For 30-year-old brother Brent, things were less definite.

“I just kind of fell into it,” he said. “I was always looking for something else to do, but I just got drawn back into helping out.”

Both of the Bonino brothers studied agriculture at Cal Poly – Russ ag engineering, and Brent ag business. Today, Russ works mainly on the farming operations side, while Brent concentrates on the fruit stand.

“What keeps me here is being around my family, and I get to work with some really great people,” Brent said. “And I get to work outside. I don’t have to be cooped up in an office.”

The personal connection with customers has become an essential part of the Boninos’ business. The children of their parents’ long-time customers now come to buy produce with their own offspring.

“The way life is so fast-paced now, it’s getting tougher for families to sit down and have cooked meals …” Russ Bonino said. “(Our business) has a majority of the older generation that still does cook, and we have the ones like our generation where they’re trying to get back into the roots of their grandparents …

“It makes it kind of neat.”

The personal connection is a major appeal. Customers have become more like friends, providing a rapport that you don’t find in a corporate setting, Brent Bonino said.

“I like more one-on-one relationships, and I get that here,” he said.

The Boninos also enjoy educating their customers about where their food comes from.

“A lot of people think this stuff grows in the back of grocery stores,” Brent Bonino said.

But it’s definitely not all fun and games. Besides obstacles such as pests and the weather that farmers have battled for generations, farmers also face other challenges such as rising costs and city-slicker neighbors that don’t understand the noise and dust that come with tending a field.

“With the cost of everything going up, the challenge is going to be trying to survive,” said Louis Bonino.

But change and diversity have also helped keep the family’s farm alive. By doing trials for seed companies, the Boninos began growing several different crops at once. The variety has become popular with customers, and now they try to plant something new every year as a special attraction.

And with several crops going, there’s a back-up if one fails.

“We evolved into concentrating more on the fruit stand – it’s something we can offer people locally that is really appreciated,” Judy Bonino said. “They know we grow everything here and pick it everyday and it’s fresh, not something they can find at the grocery store.”

Like the Boninos, George Chiala Jr. enjoys the interpersonal aspect of working at his family business, Morgan Hill’s George Chiala Farms.

Although Chiala Jr., 28, has been involved mostly on the business and processing side – brother Tim, 25, is involved more in the produce stands – he still finds a unique kind of relationship among those who work in agriculture.

“I really enjoy the people in this industry and the people I meet with,” Chiala Jr. said. “Everyone is for the most part very humble, very willing to help.”

The two men began pitching a hand when they were young children. As a teen, George Jr. progressed from driving a forklift to helping with quality control in the processing plant.

Even while attending college, he helped out on nights and weekends. After earning a master’s of business administration degree with a concentration on food and ag business from Santa Clara University, he got involved in sales and marketing for the company’s processing operation. His brother earned a crop science and ag business degree from Cal Poly and works handles sales for fresh produce and fruit stand.

“I always liked being out there and being outside,” said Tim Chiala. “When it come down to it, my dad’s business was going strong and there was room for me. It seemed like a good thing to do.”

Together with parents George Sr. and Alice, the family are all involved in the Hill Road business and its 350 acres of fields, which produce mostly garlic, peppers, corn and berries, both fresh for area residents and processed for major food companies and their pasta sauces and soups. Adult sisters Christi and Nicole also lend a hand.

“It’s really nice,” George Jr. said. “I’ll have lunch almost every day with my dad, my mom or my brother – and sometimes everybody.”

Meanwhile in the San Juan Valley, the 60 acres of walnuts and apples tended by 56-year-old Antony Freitas and 100 acres by his 73-year-old cousin Bernie carry on the agricultural tradition of a large extended family.

“The vine is shriveling up, and we’re the last two on it,” said Anthony Freitas.

The Freitas family’s presence in San Benito County began as a classic immigrant tale that began in the late 1800s, when Anthony Freitas’ grandfather M.D.A. Freitas – then just a boy – immigrated from his native Portugal to Hollister and evolved into a self-made man.

“He didn’t know English and he didn’t know anybody,” Anthony Freitas said of his grandfather. “He was just 15 years old and alone. He had a dollar in his pocket.”

Taken under wing by another Portuguese man, he was soon helping to dry-farm 1,000 acres. He was successful enough to buy his own ranch, marry and build a house and support a family.

Anthony Freitas’ father Manuel Jr. was driving a team of horses on that ranch by age 10. When he was grown, he bought property and eventually made the transition to orchards, growing strawberries and potatoes between the rows to hold them over the years it took for the trees to mature. The farm’s fancy pears were shipped as far away as Liverpool, England.

“The whole San Juan Valley used to be nothing but orchards,” Anthony Freitas said.

Anthony’s involvement was natural. He saw his father and uncles farming and admired them, eventually joining Future Farmers of America along with his brother in high school and – of course – learning many lessons on the family land.

“My dad gave us the apricots – we had a small piece and it was ours,” he said. “We were responsible for pruning it, getting up and lighting the smudge pots so those things didn’t get killed by the frost. When we’d come home from school we’d come home and do stuff for our dad on the ranch.

“My dad was good to the two of us, so we just stayed and got the ranches.”

Freitas made a promise to continue farming out of respect for his father, whose life and teachings he praises repeatedly. Manuel Freitas Jr. passed away in 2001 at the age of 97.

“When my dad passed away, I made a promise to him: ‘Dad, as long as I can hang on and take care of your places just like you were here, I’m gonna do it.’

“I’ve just been trying to keep it going for him, you know, keep his legacy going.”

It helps that he also loves the job. To Freitas, there’s nothing better than being a farmer.

“It’s a great life, he said. “You’re your own boss and everything.”

But yet, it’s getting harder and harder to stay in agriculture, between the rising expenses and increasing foreign competition.

“I’m getting the prices I got years ago – they’re not going any higher – but my expenses are getting higher,” he said. “Fuel is higher, electric is higher, everything is higher. It’s hard to make a living on the ranch.”

Over the years, the prunes, apricots and pears have gone away. Freitas ploughed up the last of the pear trees a few years ago in frustration, after the fruit fetched no value.

Freitas would love to work with his two grown sons, but doesn’t see a solid future for them in farming. Both are pursuing careers in other areas – one is assistant superintendent at San Juan Oaks, and another will probably enter the business world after San Jose State.

“I’d love to have them on the ranch like my dad did, but it’s getting impossible,” Anthony Freitas said. “I don’t want them to be struggling. It’s getting to the point where farming just goes out the window.”

“They know how much I struggle to keep this thing going and keep it together,” he said. “It’d love to have them get into it, but it’s not really feasible.”

In the meanwhile, Freitas said he will hold on as long as he can.

“Maybe I’ll be fortunate enough to live to be 97 too – you never know,” he said. “As long as I’m able to work and keep going … ”