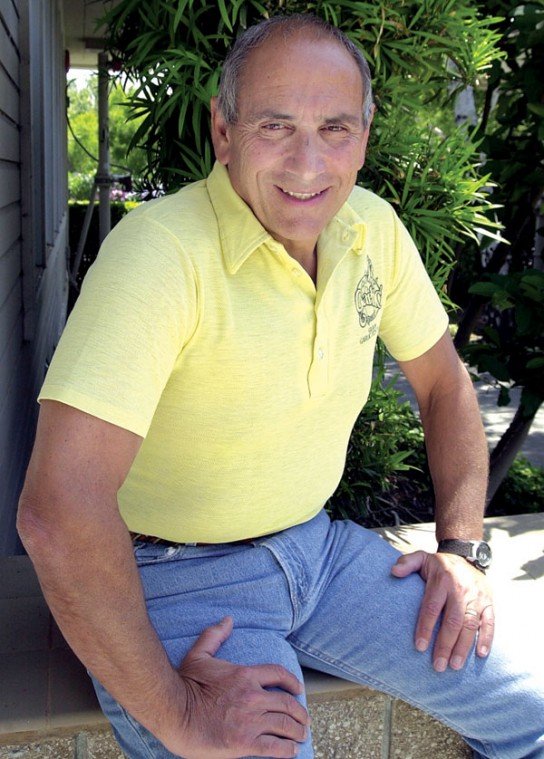

A frantic search for butter. That’s one thing Tim Filice,

president of the Garlic Festival in 1982, remembers from that

year.

A frantic search for butter. That’s one thing Tim Filice, president of the Garlic Festival in 1982, remembers from that year.

“I guess the single most significant impression I have is, in the early years we were really flying by the seat of our pants,” he said. “We were constantly underestimating the response. We were amazed at the increasing number of people coming in.”

Filice is a partner at the Glen Loma Group, a local real estate and development firm. He was the first chair of Gourmet Alley which was conceived for the second festival in 1980, and he recalls the frantic pace the festival had in those early years when it was still evolving as the nation’s premier cuisine gathering.

“We were always scrambling around,” he said. “Seems like 2 o’clock on Saturday we would be scouring every grocery store and supermarket in the county and also San Benito County for butter and other ingredients.”

The butter was an absolute must for various dishes including, of course, the popular garlic bread. And on the festival’s Saturday afternoon in 1982, Filice received a call that there wasn’t a pound of butter to be found anywhere south of San Jose.

“Those were exciting years because you didn’t know what to expect,” he said. “We were always in reactive mode, being amazed by the number of people showing up. It was great fun in those early years.”

In 1982, about 110,000 guests showed for the fest, he recalls, and that was an amazing number in those years. Now, the festival can expect around 125,000, so the organizers are better prepared to handle the crowds.

“There’s comfort there,” he said, in knowing how many guests to expect for dinner. “But it kind of lacks the excitement of the early years.”

The festival has given Gilroy a lot more than just financial stability for nonprofits and a sense of pride in the local garlic heritage. It has been a “learning seminar” in management and organization for many of the local citizens who have participated, Filice said.

“Those organizational skills, the (volunteers) take with them back to their own organizations, be it Gilroy Gators (Swim Team) or the Elks or whatever,” he said. “It’s taught people how to put on events small and large. It’s an organizational skill that has been developed here. There’s a whole lot of people here who know how to get things done in terms of organization.”

It has also provided local organizations with a dynamic networking resource.

“This community has a way of getting things done,” he said. “And you just know if you have a challenge, you want to put on an event here or raise money, immediately a short list of people comes to mind. You know who to call.”

As a pioneer of the festival, Filice played an important role in expanding it to include the Ranch Side part of Christmas Hill Park. At that time, it was an agricultural field, dusty and flying with insects.

Today, it is developed with lawns thanks to money brought in from the festival.

Another part of the evolution of the festival during the 1982 year came in the approach of divvying up the profits from Gourmet Alley.

“The challenge was we’ve got to keep it fair and equitable for all volunteers,” Filice said. “We’ve got to keep them coming back because they are the life blood of the festival.”

That year, a committee came up with an “all-for-one and one-for-all” plan where the volunteers in the massive food tent would split the total profits for their nonprofit organizations based on man-hour time. The idea would later spread to incorporate all of the festival volunteers, he said.

Volunteers are necessary for the festival’s future, Filice said, and it’s vitally important for the event’s success to make sure they’re happy contributing, or they won’t come back the following year.

“You could never afford to put on this event and actually pay people to do it,” he said.