Coyote Valley

– Richard DeSmet has a passion that is as frustrating as it is

fulfilling. Once every few weeks, DeSmet stands before San Jose

planners, council members or developers and spends two minutes

exhorting them to change the way they think about the Coyote Valley

greenbelt. Then he sits down, convinced

that his two minutes were in vain.

Coyote Valley – Richard DeSmet has a passion that is as frustrating as it is fulfilling. Once every few weeks, DeSmet stands before San Jose planners, council members or developers and spends two minutes exhorting them to change the way they think about the Coyote Valley greenbelt. Then he sits down, convinced that his two minutes were in vain.

“We’re learning how this process works. If we don’t speak, the assumption is that we’re in agreement,” DeSmet said recently. “But they don’t listen to what we have to say. They put up with our comments because they have to; they don’t do anything with our suggestions.”

DeSmet owns 51 acres in the greenbelt. In the last year he has become in many ways the public face of the Greenbelt Property Owners Association, and one of the most vocal critics of San Jose’s plan for turning north and mid-Coyote Valley into a live-work community of 80,000 people, at, he says, the expense of those in the greenbelt to the south.

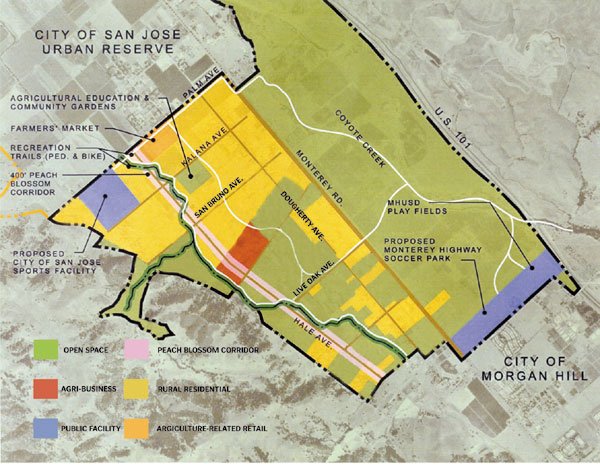

The Coyote Valley Specific Plan calls for the 3,600 acres of Coyote Valley immediately to the north of Morgan Hill to be preserved in perpetuity as agricultural and open space. It’s a concept that the plan itself acknowledges as “part dream, part reality.”

“That’s the key phrase,” DeSmet said. “There’s nothing to save, environmentally, west of Monterey, because it’s a semi-urban area. Just because they draw a line on a piece of paper, that doesn’t make the dream a reality.”

DeSmet said that he and his fellow property owners want to be “good stewards of the land,” and preserve its heritage.

“We all have that as our common goal. We want to see the best use of the property. We’re all for Coyote Valley. We’re all for the greenbelt. But if they want to make it an open space, we want to have some input.”

The property owners

San Jose has had various schemes to develop Coyote Valley for more than two decades, but the process began in earnest about five years ago, when Cisco Systems Inc. agreed to construct a major corporate campus in northern Coyote. That project is waiting for another economic boom, but the city has moved forward with its plan, assuming the economy will catch up by the time its ready to break ground.

In October 2001, San Jose announced its intention to change the zoning of south Coyote from rural residential to agriculture greenbelt. The first incarnation of the owners association formed to fight that proposal and lost, but it has grown steadily since, through the first two and half years of the planning process. Meetings draw an average of 50 people, occasionally more than 100.

There are many vocal members who take their turn at the podium right behind DeSmet, but it’s DeSmet’s name on letters of opposition, it’s DeSmet who makes local TV appearances, and it’s DeSmet who members give the most credit for keeping the group moving forward.

“He’s the fellow who’s been spearheading the movement,” said member Dan Carroll. “He’s recruited a lot of people and has a lot of followers. They’re the ones keeping our movement alive.”

DeSmet, 56, grew up in the greenbelt, on a prune farm worked by his father and grandfather. As the prune industry left the Santa Clara Valley for the Central Valley, the economic viability of the DeSmet family’s 51 acres went with it. The cooperative dryer in Morgan Hill closed down, leaving Yuba City as the only processing option for local prune growers.

Prune farmers couldn’t compete on their own. The DeSmets also tried growing garlic, bell peppers and tomatoes. About 20 years ago, DeSmet leased the land to turf farmers.

“As far as we’ve been able to find, it’s the only agricultural enterprise (in the greenbelt) that’s economically viable,” he said.

DeSmet has led an eclectic life. He graduated from Willow Glen High School and the University of the Pacific, and then enrolled in the Navy. After his military stint, he took a sales and marketing job with Caterpillar Inc. The company sent him first to Peoria, Ill., and then to Geneva and Munich, Ger.

When he married his wife, Gail ,they moved to Spokane, Wash., where DeSmet opened his own business, Leland Trailer and Equipment Co. Inc., which he still owns. He brought his family back to California in that late ’80s. Since then, he’s been involved in a few business ventures. He lives in Almaden. Five years ago, he joined South Valley Church.

“I was transformed,” DeSmet said. “I learned the power of love turning into action. I’ve put in so much time with Coyote Valley, it’s got to be out of love. The community inspires me.”

The association carries no formal dues, but members whom DeSmet describes at the “most interested” have contributed a considerable amount of money to pay for attorneys and the group’s own efforts at conceptual land use design.

Eric Flippo, a member who farms 20 acres in the greenbelt, said that DeSmet has been “incredible” in leading the group.

“He’s very good at what he’s doing,” Flippo said. “He’s being very unselfish. He spends countless hours working for free, helping all of us.”

The future of the greenbelt

Greenbelt owners talk often of their love for the land and their desire to see its heritage protected, but they rarely express an interest in holding on to the land. Like DeSmet, many of them lease their land and live somewhere else. For the right price, they’re eager to sell.

“Because of the situation, because of the limitations, we would like to sell,” DeSmet said. “If they will allow us to have some clustered housing, we’re willing to donate some percentage of the land for open space.”

Property owners have given the city three draft proposals of land use designs for the greenbelt, each of which calls for a mix of agri-business, open space and clustered residential housing. Presumably, allowing developers to subdivide and build housing will raise land values.

DeSmet’s parcels are among those that the greenbelt owners have designated for development, but he says that “this is not about money. What we want is true economic value for our land. We don’t know what that is, it depends on demand.”

And the only way to gauge demand accurately, he said, is for the city to remove its development restrictions.

“The city is looking at this as a buy-sell agreement, but as buyers they want to dictate all the terms of the deal,” DeSmet said. “They try to minimize the value of the property because the specific plan won’t go through unless they can come up with a plan for the greenbelt.”

DeSmet’s plan includes a greenbelt that he says is actually green. A few houses surrounded by protected open space. An end to the patchwork of failing and disused agricultural operations. He doesn’t want to literally hand down his land to this three children, but he hopes they’ll be able to visit it one day.

“It would be fantastic for generations of our families to be able to take a walk around there,” DeSmet said. “In the end, we’re only here for a short time, and if this does or doesn’t get settled in my lifetime, I can pass this on to my children.”