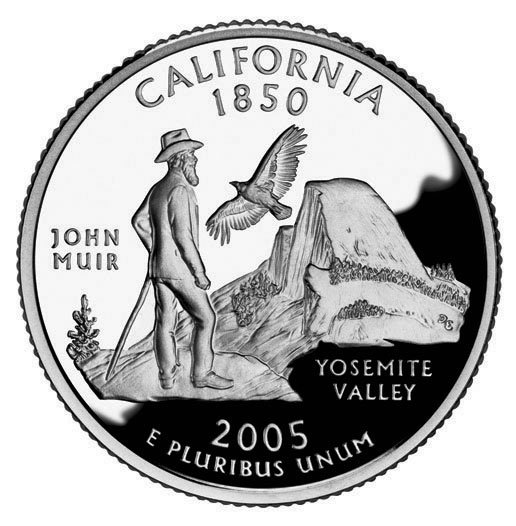

A couple of years ago, America honored John Muir by putting his

image on the U.S. quarter. The special state coin commemorates the

famous Victorian naturalist by showing him gazing at Yosemite’s

Half Dome.

A couple of years ago, America honored John Muir by putting his image on the U.S. quarter. The special state coin commemorates the famous Victorian naturalist by showing him gazing at Yosemite’s Half Dome.

John Muir is the greatest Californian. I have no hesitation making that bold statement about our nation’s most important environmentalist, a man who ignited a movement to save America’s wilderness from exploitation. Interestingly, the South Valley played a pivotal role in Muir’s achieving his ambition of preserving much of the landscape of the American west. His life work began with a long walk he took in 1868 that passed through our region.

In late March that year, the Scottish-born Muir reached San Francisco by steamship via Panama. Upon arrival, he asked a carpenter, “What’s the quickest way out of the city?” The workman replied. “Where do you want to go?” Muir responded “Anywhere that is wild.”

Those words set him off on a jaunt to witness for himself California’s Sierra Nevada mountains. The journey was relived last April by Peter and Donna Thomas, a Santa Cruz couple now working on a book (scheduled to be published next year by Wilderness Press) that will recount their modern re-enactment of Muir’s wilderness walk.

Recently, I called up Peter Thomas to find out how Muir might have seen our own region when he first passed through here. I learned that after Muir began his tour by taking a ferryboat ride from San Francisco to Oakland, he headed south on his walk and a few days later arrived in San Jose. The quiet farm village still had vestiges of its Spanish- and Mexican-era pueblo days.

Muir continued on his long amble by following Monterey Road south, Thomas told me. The naturalist certainly must have felt enthralled by the grandeur of the green hills, cattle-dotted oak plain and running creeks when he passed through the ranch of South Valley pioneer Daniel Murphy. The land would someday be the town of Morgan Hill.

The young Muir had studied botany at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, so he was particularly keen on the floral displays he saw in our region that spring day 139 years ago. “He wrote with the same sort of fervor and reverence for the Santa Clara Valley, in the same tone that he wrote about the Sierras.” Thomas said. “He spoke about the flowers as sheets on the hillside. He wrote about hills blooming all around him with color.”

Knowing Muir’s adventurous inclination, I imagine he quickly trooped up the volcano-like Murphy’s Peak (now known as “El Toro” on Morgan Hill’s western boundary). From that lofty vantage point, he must have long gazed out at the South Valley terrain.

He’d later write of this valley vista: “The last of the Coast Range foothills were in near view all the way to Gilroy. Their union with the valley is by curves and slopes of inimitable beauty. They were robed with the greenest grass and richest light I ever beheld, and were colored and shaded with myriads of flowers of every hue, chiefly of purple and gold yellow. Hundreds of crystal rills joined song with the larks, filling all the valley with music like a sea, making it Eden from end to end.”

According to Thomas, Muir reached the village of Gilroy between the 15th and 20th day of April 1868. The great naturalist had a pocket map, but it contained little detail about how to head toward the Sierras. “When he got to Gilroy, he asked the way and they said, ‘You cross over the Pacheco Pass, and good luck after that,'” Thomas told me.

Muir continued his wilderness wandering by heading east and trekking through the pass route so many modern commuters now daily follow through the Diablo mountain range. The springtime scenery certainly was awe-inspiring for him then as it is for us now. Take a hike through Henry Coe State Park or Pacheco State Park in the South Valley right now at the peak of their verdant vitality and you’ll see the same rugged landscape the naturalist encountered.

Although nobody knows when Muir actually reached the summit of the pass, I’d like to imagine he arrived on the morning of April 21, his 30th birthday. And what a fine birthday gift he received from Mother Nature as he stood on Pacheco Peak and gazed toward the rising sun.

“Looking eastward from the summit of Pacheco Pass one shining morning,” he later wrote, “a landscape was displayed that after all my wanderings still appears at the most beautiful I have ever beheld. At my feet lay the Great Central Valley of California, like a lake of pure sunshine, 40 or 50 miles wide, five hundred miles long, one rich furred garden of yellow composition. And from the eastern boundary of this vast golden flower bed rose the mighty Sierra, miles in heights, and so gloriously colored and so radiant, it seemed not clothed with light, but wholly composed of it, like the wall of some celestial city.”

At that moment, Muir christened the Sierras “the Range of Light,” a description still used to convey its grandeur.

If Muir were alive today, I believe he’d continue pushing for the preservation of America’s wilderness.

His fight continues on as a greedy few seek to exploit our natural resources for short-term profit. Muir would encourage us to venture forth “anywhere that is wild” because he knew that experiencing natural beauty is good for our souls and refreshes our human spirit.

By coincidence, Muir’s April 21 birthday today concurs with a Morgan Hill fund-raising barbecue for Jerry McNerney, our local congressman. The event will promote the protection of our natural environment through the national development of clean and renewable energy.

At the barbecue, a birthday cake will have on it the image of the quarter coin honoring John Muir. It symbolizes that the spirit of the greatest Californian still saunters through our 21st century South Valley region.