Local skeptics of the California High-Speed Rail Authority’s

grand vision of bullet trains zipping up and down the state at 200

mph voiced their concerns at a recent public meeting.

Local skeptics of the California High-Speed Rail Authority’s grand vision of bullet trains zipping up and down the state at 200 mph voiced their concerns at a recent public meeting.

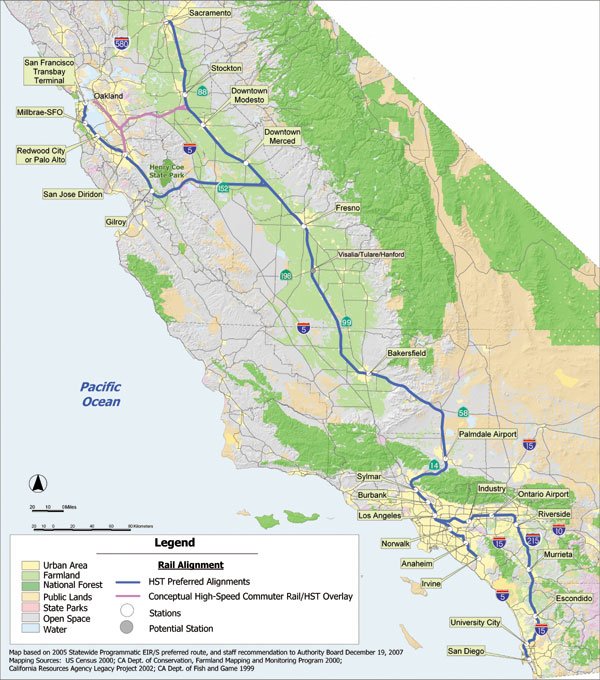

The rail authority presented construction options to about 50 locals gathered Monday night for a scoping meeting at the Hilton Garden Inn. The trains, which will run along 800 miles of track from San Francisco and Sacramento in the north to Los Angeles and San Diego in the south, will eventually carry 93 million passengers annually, according to the authority’s projections. Locally, the preferred alignment runs up the Central Valley, tunnels east through Pacheco Pass, then heads north toward San Jose, with a stop in downtown Gilroy.

But Rod Diridon, who sits on the rail authority’s board, reminded residents that nothing is set in stone and the authority will go through several public input sessions to stay abreast of community concerns. The project, however, will happen, he said.

“Don’t think anymore that it ‘might’ happen, that it ‘could’ happen, or that we have to do it on a shoestring budget,” Diridon said. “We have a project and adequate funding to do a good job.”

He likened the authority’s vision to the high speed trains running in Europe and Asia.

After listening attentively to the 30-minute presentation outlining the authority’s next steps and alternate routes, concerned residents piped up about noise, funding, the lawsuit Bay Area communities Atherton and Menlo Park filed against the rail authority, tunneling, and more.

One resident asked how the lawsuit filed against the rail authority would affect the project. The lawsuit, filed by the towns of Menlo Park and Atherton and environmental groups, challenged the rail authority’s decision to run bullet trains reaching speeds of 220 mph over Pacheco Pass and up the Peninsula instead of Altamont Pass and the East Bay. The plaintiffs contend that the project’s environmental impact report failed to provide sufficient detail on the Pacheco alignment. The report described an alignment along existing Union Pacific Railroad tracks between Gilroy and San Jose.

“That’s up to the judge and attorneys,” said Dave Mansen, a regional project manager for the rail authority. “Our attorneys have asked us not to comment on the specifics.”

Mansen would say, however, that the presiding judge chose not to issue the stop work order requested by the plaintiffs.

Concerned with the impact of the bullet train on the landscape, other residents suggested submerging the trains completely underground.

“You would destroy downtown Gilroy with a trench that’s 120 feet wide and divide our community more than it is now,” said resident Sherri Stuart. “To divide our community with a trench would be appalling. Has a tunnel even been discussed?”

“Not yet but that’s why we’re here tonight,” one of the authority representatives responded.

One option for Gilroy includes a trenched design running through the downtown with a station at the current Caltrain station on Monterey Road at Eighth Street. Two tracks running in each direction will carry both local and express trains. Other options include a raised track or moving the alignment altogether and running it somewhere east of U.S. 101. Currently, the high speed rail tracks cannot cross the existing Union Pacific Railroad tracks, posing another dilemma.

Tunneling is expensive, and the cost might fall on the shoulders of the city. Stuart said she had heard mixed information from sources about who will have to pay for each town’s station and track alignments. When she asked high speed rail officials for a definitive answer, they confirmed that the authority planned to outfit the cities with the basics but anything “above and beyond,” like a tunnel, might come out of the cities’ pockets. Niether local nor rail officials could not put a dollar figure to those particular costs.

And when another resident asked about the noise, Mansen pointed out that unlike the trains that currently run on the Union Pacific tracks, high speed trains would not blow their horn because they would always be at a different grade than the roads and highways, authority officials said.

“For those that hear that,” Mansen said, referring to the muffled train horn that sounded almost as if on cue, “high speed rail trains don’t blow their horns.”