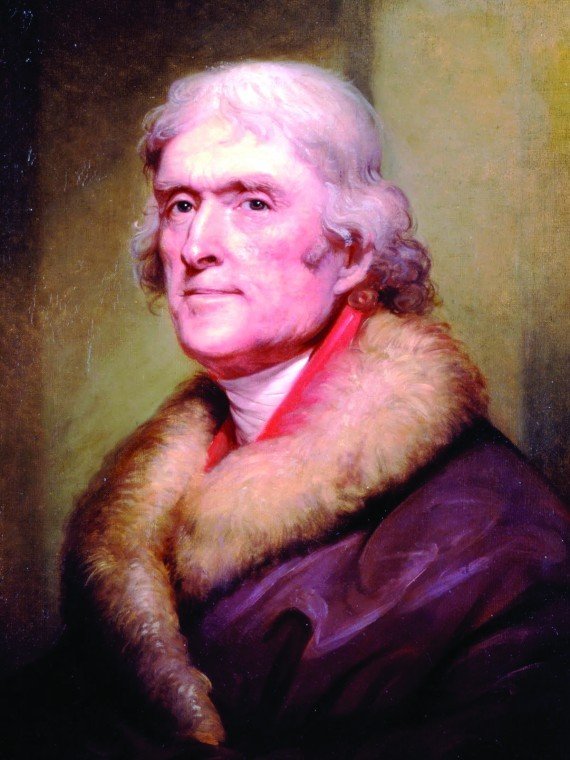

People from all over will come to the Gilroy Garlic Festival this weekend to sample the gastronomical delights in Gourmet Alley and munch on an assortment of victuals from various vendors. If you attend South Valley’s biggest culinary event, please raise a glass of wine in toast to America’s first “foodie.” I’m referring to my favorite Founding Father from Virginia, Mr. Thomas Jefferson.

The author of the Declaration of Independence, among his many other notable accomplishments, contributed much to influencing our nation’s cookery traditions. His zeal as a fine food connoisseur helped lay the foundation for America’s food experimentation that eventually led to Gilroy’s annual garlic extravaganza. We can find his spirit at the festival.

Jefferson truly delighted in quality cuisine. He had his kitchen slaves study with the best chefs of Europe so that they could bring their cooking techniques back to Monticello, his mountain-top Virginia estate. During his time as an ambassador, Jefferson gathered recipes from France and northern Italy, which his granddaughter, Virginia Randolph, collected. The recipes from this collection were included in a cookbook called “The Virginia Housewife,” published in 1824 by Jefferson’s cousin Mary Randolph. Culinary historian Karen Hess considers it the most influential book to shape American cooking in the 19th century.

Jefferson would appreciate our modern organic gardening movement. He was an experimental horticulturalist with a vast kitchen garden at Monticello where he grew 330 varieties of imported herbs and vegetables to enhance America’s traditionally bland food choices. Sprouting from the soil of his garden were Mexican chilies, midnight eggplants, Native American lima beans, African okra, French artichokes, 15 types of English peas (green peas were his favorite vegetable) and Native American corn brought back from the Lewis and Clark expedition. Monticello’s orchard included 170 varieties of fruit trees and berry bushes. Following a philosophy of diversifying the American diet, Jefferson shared seeds from his estate with other Southern plantations to encourage new crops for a new nation.

No doubt, if the third United States president were still alive, he would enjoy a day at the Gilroy Garlic Festival. And no doubt, he would sample some garlic ice cream. Jefferson was a big fan of this frozen dessert, and he frequently served it to his White House guests. His recipe was simple, bringing together heavy cream, eggs, sugar and vanilla beans in a concoction that was a concerto of flavor playing on his guests’ taste buds. He even came up with a recipe to serve balls of vanilla ice cream encased in a hot pastry, a prototype of the dessert we now know as baked Alaska.

My favorite Jefferson culinary story involves an Italian pasta machine he brought back from Europe after spending time there as the American ambassador in France. For an 1802 state dinner, Jefferson had his White House chef prepare a batch of macaroni using the machine. He then instructed the chef to mix fresh butter and Parmesan cheese into the pasta and cook it in a 400-degree oven. Jefferson’s “macaroni pie” was served to the guests to great acclaim. The dish that was celebrated at a White House state dinner would later serve as the basis for our own mac and cheese staple of the American diet loved by kids for generations.

At Monticello and the White House, Jefferson would often give elaborate dinner parties where guests were treated to delicious meals accented with fine wines imported from Europe. Jefferson understood that food can be a tool of statesmanship. There’s something about human nature where tensions can often ease when we join together for culinary revelry. Jefferson understood that when people gather together at a table and share a first-rate meal and a glass or two of vino, they tend to set aside their ideologies and agendas and start to see each other in a more convivial light. Perhaps Jefferson’s insight in mixing fine food and affairs of state might help our current contentious crop of members of Congress overcome their enmity.

And I’m sure Jefferson would appreciate the words of Marion Cunningham, a champion of home cooking who died recently in Walnut Creek at the age of 90. Cunningham wrote recipe books including the classic “Fannie Farmer Cookbook.” In her forward to the book “Lost Recipes,” she wrote: “Home cooking is a catalyst that brings people together. We are losing the daily ritual of sitting down around the table (without the intrusion of television), of having the opportunity to interact, to share our experiences and concerns, to listen to others.”

For the future of the American republic which he helped establish, a certain Founding Father foodie from the Commonwealth of Virginia would wholeheartedly agree with Cunningham’s sentiment.