Old Gilroy refers to the settlement that had built up around John Gilroy’s adobe, on what is now the southeast corner of Pacheco Pass Road and Frazier Lake Road. That village was actually called San Ysidro, but leading up to and following the Gold Rush, newcomers, both fur trappers and 49ers, who were mostly sympathetic to the South in the Civil War, had preferred to call it Gilroy.

Present day Gilroy sprung up as a viable town following the arrival of the train in 1868, which brought people looking to settle here from mostly northern states. Northerners valued their towns and civic order. In the next few years they had set up a pro-Union newspaper, a number of churches, established a municipal water system, hired a Marshall, set up telegraph, a fire company, and started businesses downtown.

“The present town of Gilroy is built some two or three miles from the old town of Gilroy and considering that the place has been mostly built up within the last six months, it is a right smart town.”

—San Mateo County Gazette, March 27, 1869, “A Ride to Gilroy”

By 1869, Mexican California was in eclipse, the native population had been decimated, tensions were still very high following the Civil War, and anti-Chinese sentiment was at a fever pitch. Murders, arson and highway robberies were frequent, especially arson (then called “incendiarism”).

“Already considerable property has been given to the flames, and our exchanges, almost daily, bring us tidings of some attempted or consummated act of incendiarism, or some ‘warning’ to persons who have come under the ban of this California ‘Ku Klux Klan’… There is an unmistakable chain of connection between the torches which has made bonfires of both public and private property and the Democratic Party of California.”

—Gilroy Advocate, May 22, 1869, “Cause and Effect”

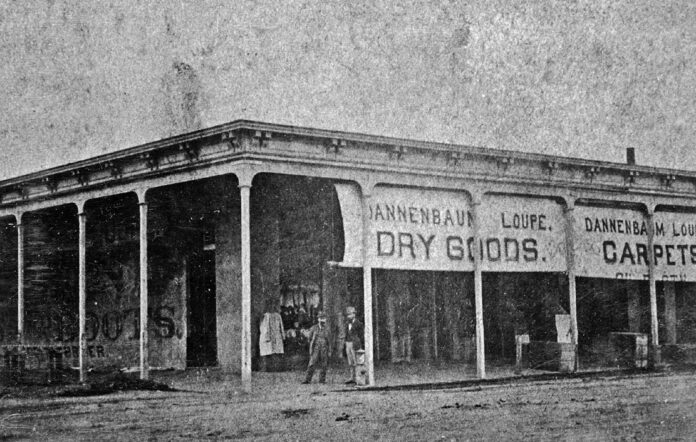

Enter A. Rosenthal, a businessman who started a dry goods store near the northwest corner of Fifth and Monterey streets. His business had burned down and he was thought to have started it himself. There was an obvious trail of evidence (rags soaked in coal oil, kindling, etc.). He was described as having grown very pale and quiet when accused. Had this been insurance fraud?

Many prominent Gilroyans didn’t think so. He was discharged by Judge Perry Dowdy. The insurance company sent a special detective who then had him rearrested by Officer McElroy of Santa Clara. A mob showed up to free Rosenthal and arrested McElroy, saying “We run this town” (Gilroy Advocate, March 13, 1869, “We Run This Town”).

So the famous Sheriff John Hicks Adams was sent to Gilroy to arrest Rosenthal and had some trouble finding him. J. Sevenoakes had him in custody at the Station House. Adams requested the key, but the Marshall refused. Sheriff Adams moved to arrest the Marshall.

“The Sheriff called upon the citizens of Santa Clara to arrest him, and the Marshall invoked the aid of the Gilroyites. A little skirmish was indulged in, but the Gilroyites generally took sides with the sheriff, and the refractory Marshall was taken in charge, together with his aids, P. Francis Hoey and J. Sevenoakes… The procession then moved down Fourth to Eigleberry Street and to the cars. In a few minutes, Capt. Adams, Deputy McElroy, Rosenthal, Hoey, and Sevenoakes, together with counselor Tully and witnesses were aboard and speeding northerly to San Jose.” —Gilroy Advocate March 27, 1869 “Taken to San Jose”

Questions, comments and other information can be sent to gi***********@***il.com.