Varied AP exam results have GUSD officials examining teacher

training, student attitudes

Gilroy – Scattered results on the this year’s Advanced Placement passing rates have left district officials questioning how to bridge the performance gaps.

Without a positive growth pattern across the 11 AP tests Gilroy High School students took – officials will examine factors such as teacher training and course alignment with student preparedness and attitudes to help increase the passing rate.

While strides were made in English Literature and Biology scores, a severe drop in the percentage of students passing the Calculus exam may be indicative of a districtwide problem.

“I see them as very inconsistent,” said Gilroy Unified School District Superintendent Edwin Diaz.

He is uncertain whether teachers need to be more aligned with the AP curriculum or students need to be more prepared.

“Whatever the reason, the results need to be improved,” he said.

In order to pass the AP exam, a student must score a three or above on a scale of one to five. Courses are designed to teach college level material to high school students. The curriculum is taught nationwide, however the materials and textbooks vary.

Many colleges give credit to students for scoring at least a three on the AP exam.

Over the past four years, the number of students at GHS enrolling in AP classes has increased about 20 percent.

A report to GUSD board members on Aug. 18 left some questioning whether increased enrollment has overextended resources, causing performance to drop, or whether students are not adequately prepared.

A simple glance at the passing rate shows whether numbers went up or down compared to the year before. What is not shown is the percentage of students enrolled in a class who take the exam and pass. GHS students are not required to take the AP exam.

“The percentage pass rate is a reflection of the number of students who take the test. If a school decided only to encourage students whose teachers believed they had a good chance of passing to take the test, the number of students goes down and the percentage increases,” said AP English teacher Peter Gray.

While 35 percent of his class scored a three or above on the exam this year, more students took the exam than the year prior when 34 percent passed, and several more students scored four’s and five’s on the exam than in 2002-03.

“A larger number of students passing and getting four’s and five’s is more important than the percentage,” he said.

Gray offered more test preparation this year than he has ever before.

“I retooled my class to be a hybrid of close reading and rhetoric with more test prep,” he said. “I plan on analyzing the individual student’s scores with their performance on in-class essays, their letter grades … to work toward increasing the number of students who pass.”

In seven instances where enrollment increased, scores decreased. However, district officials are not jumping to conclusions.

“There’s not an absolute correlation at this point,” Assistant Superintendent of Administrative Services Jackie Horejs told board members.

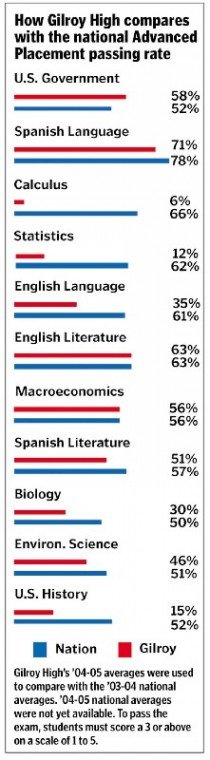

In the past three years, students taking AP subjects such as Spanish Literature, Spanish Language, Government and Macroeconomics have consistently scored on par or above the national passing rate. Biology and Statistics scores have generally been far below the national average.

Ayeola Boothe Kinlaw, Director of Equity and AP Access Initiatives for the College Board, said that often, when students are consistently scoring extremely low on AP tests, there may be a problem earlier on in a district’s curriculum.

“Find out what is expected in that capstone (AP course) and draw all the way down,” she said. “Think about vertically aligning the curriculum so that you are filling in the gaps and AP teachers are not doing remedial work.”

The release of the 2004-05 Standardized Testing and Reporting program last week showed that math continues to be an area where GUSD students struggle at an early age.

But gaps in a curriculum may not be the only explanation.

“The AP exam is a direct reflection of the AP course guideline … but only if the teacher is teaching to the course guideline,” Boothe Kinlaw said.

Teachers are not required to attend specialized AP training, but are strongly encouraged by the College Board.

The exam changes over time as the AP test is realigned with college instruction.

“It could be that the content changed and the teacher didn’t know it,” she said. “We strongly encourage districts to pay for their teachers to get training.”

GUSD board member David McRae hopes to explore the idea of requiring prerequisites for students to enroll in AP classes, such as math.

“I don’t want prerequisites for the sake of prerequisites – I don’t want to exclude people who can succeed,” he said. “But how can you take Calculus if you didn’t pass Algebra? It’s like taking literature and you don’t know read … It’s like setting someone up to fail.”

McRae believes the there isn’t one solution. He wondered about some student’s motivation for taking it in the first place.

“Is this a prestigious thing that the parents push their children to do even if their heart isn’t in it?” he asked.

While the answer may be unknown, he does believe that teachers need to teach for the AP test.

“In AP, you begin the first day of school knowing there’s a test at the end,” he said. “The whole class should be taught to the exam … When you have to take the driver’s test, you practice what’s on the exam.”

According to McRae, measuring GHS’ scores against the national average is imperative.

“If you’re afraid to measure something, there’s usually a reason,” he said. “It’s great that we’re having this discussion because everything that comes out of it will be positive.”