SAN JOSE—The Santa Clara Valley Water District, water wholesaler to 1.8 million people, has championed local conservation. The public agency runs three treatment plants for drinking water. It also manages 10 dams and reservoirs, 400 ponds that replenish our groundwater and 275 miles of creeks and streams.

In late April, the water district’s seven-person water district board authorized CEO Beau Goldie to bypass competitive bidding and execute $10 million in single-source contracts. Goldie argued that there was no time to undertake a qualification process, and he was granted extraordinary executive powers by a 5-2 vote. After the vote was taken, details emerged about the largest of Goldie’s deals: a proposed $4 million payday for the RMC Water and Environment.

The district had awarded RMC $10.7 million in 2009 to design a Morgan Hill and San Martin flood control project. As the state’s water crisis deepened, RMC expanded its services to include groundwater replenishment.

In proposing the RMC deal, CEO Goldie neglected to disclose two material facts: first, one of his top deputies is married to a company principal; and second, just weeks before the water district granted him authority to draw up a deal, ex-Monterey County water board member Steve Collins pled no contest to criminal charges for accepting $160,000 in illegal payments from RMC.

Interviews and and a review of emails, budget memos and staff reports has identified evidence of a serious conflict of interest and documents which appear to show that top executives ignored concerns that RMC fraudulently billed the district for half a million dollars.

Melanie Richardson, a deputy administrator at the water agency, is the wife of RMC co-owner Tom Richardson. A former RMC executive recalls meeting her at RMC company holiday parties. Her husband, meanwhile, is actively involved in managing his firm’s business with his wife’s employer. Just six months ago, on March 14, he provided a presentation on the South Bay Water Recycling Strategic Master Plan to a joint committee of the district and the cities of San Jose and Santa Clara. His civil engineer’s stamp appears on the cover of the master plan report, which outlined new capital spending projects and financing options.

The ‘Firewall’

CEO Goldie has repeatedly argued that RMC is the most qualified company to kickstart the county’s proposed $800 million potable reuse water project. The claim, however, remains untested since no open bidding or qualification process ever occurred.

In a phone interview this summer, Melanie Richardson said a “firewall” was put in place by the district to prevent her from having any involvement in RMC business. Emails suggest a policy started in December 2009, when she told staff to exclude her from all matters related to the company. But six months before that time, she and the water district signed off on two RMC contracts totaling more than $10.6 million.

Melanie Richardson was a deputy administrative officer of procurement at the time. Santa Clara Valley Water District was one of RMC’s two biggest clients during the second half of the aughts, according to a source with detailed knowledge of RMC’s financials.

As deputy administrator, Melanie Richardson oversaw multiple stages of the consultant contract review and approval process. But in presentations she delivered to the Board of Directors in February and August of 2009, no mention was ever made of her husband’s financial interest in RMC.

Complaints were sent to the District Attorney’s office in 2013, but no charges were ever filed—mainly because the 4-year statute of limitations would have expired before the investigation had a chance of concluding.

In her conversation with the Silicon Valley weekly Metro, Melanie Richardson admitted that the firewall does not require her to leave the room when staffers discuss RMC work.

“That is not my firewall, that’s just an extra step I take,” she said. “It’s not necessarily required for me to walk out of the room.”

The district and Richardson have refused to release a copy of the firewall agreement, citing attorney-client privilege. Stan Yamamoto, the district’s lead attorney, also refused multiple interview requests, instead issuing the following statement: “As legal counsel for the District, I’m not at liberty to discuss legal advice provided to District employees.” He went on to add that he would not “comment on the opinions of unknown sources” despite the fact that requests for comment were related to specific documents.

Dick Santos, who was first elected to serve as the District 3 board director in 2000, said he is “concerned” to learn that Melanie Richardson’s firewall does not prohibit her from sitting in on RMC discussions.

“That should be part of an agreement,” Santos said, adding that he thinks the district should release the firewall agreement. “I’m for everyone to be forthcoming. There should be no hidden agendas, whether it be the with press or anybody else.”

While the agreement remains hidden, one thing is certain: the firewall has been anything but comprehensive. In addition to Melanie Richardson’s ability to attend progress reports, staffers have at times provided her with reports on RMC’s work.

“As you can imagine, sometimes staff forget and then I have to remind them,” she said. “They might ask me to sign off on a document, and I’ll say, ‘No, I don’t sign off on that document.’ You can’t expect every other person in the organization to remember this. Over time it’s gotten better.”

The firewall also failed to prevent Melanie Richardson from conducting performance evaluations of unit managers who performed oversight of RMC contracts. While her subordinates initially sent their own assessments on RMC to a different deputy for review, she was eventually given summaries of how her team members performed, including portions that related to RMC business. This changed in July, shortly after Metro’s initial report on conflicts of interest involving RMC.

Financial Authority

She does, however, author most of the five-year capital budget plan for flood control, and she manages up to 20 watershed projects, which are designed to protect people and properties from flood damage. Any budget changes above $100,000 must be signed off by the board of directors, but the complexity of the accounting makes it near impossible for part-time board members to identify irregularities in hundreds of pages of staff reports and contracts that are filled with engineering jargon, near daily amendments and abbreviated accounting figures.

District staffers say it wouldn’t be difficult for Melanie Richardson to reduce funds from one of the 20 watershed projects she controls, leaving leftover funds for someone else to channel into other existing contracts, including those controlled by RMC.

“Is it possible? I don’t think it happened,” Goldie said. “I don’t mean to be flippant here. Anything is possible, but I don’t think it happened in this case.”

What is possible—and almost certain—is that Goldie and his top administrators have ignored warnings that RMC has manipulated contracts to overbill the district by as much as $512,000.

Zero Work

Both Goldie and Norma Camacho, the district’s chief operating officer (COO), have said in interviews that RMC has been a model consultant, and there have been no issues with improper billing in the past. But internal emails acquired through Public Records Act requests suggest exactly the opposite, that Goldie and Camacho have actively turned a blind eye to fraudulent billing.

Roger Narsim, an engineer unit manager for the district who oversees RMC contracts, first sounded alarms about the fraud nearly 18 months ago. His warnings fell on deaf ears. In a message sent April 21, 2014, Narsim noted that RMC had billed the district an estimated $512,000 for work that was never done. He added that it would be difficult to recoup the money and that the district’s lone option might be withholding $46,000 in retention funds. To date that money has not been released, yet Goldie and Camacho both maintain that RMC has never had a district contract cancelled or suspended due to improprieties.

In particular, RMC appears to have received $350,000 in payments for zero hours of work related to the Lower Silver Creek “Reach 6B” project. The project’s goal was to construct flood protection on the creek so water get could safely flow from Lake Cunningham in East San Jose down to Highway 680. This would protect the communities from a catastrophic flood, the type that occurs once every 100 years.

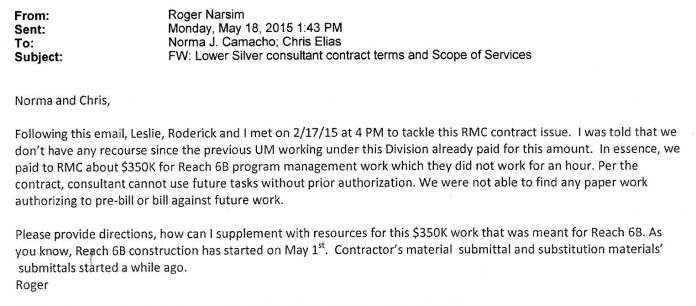

“In essence, we paid to RMC about $350K for Reach 6B program management work which they did not work for an hour,” Narsim wrote in an email this spring to Camacho. “Per the contract, consultant cannot use future tasks without prior authorization. We were not able to find any paperwork authorizing to pre-bill or bill against future work.”

Narsim has continued to inform his colleagues that RMC had violated the terms of its contract by billing the district for non-existent work. As a result, district staff has been forced to fill in the gap. In an email to a colleague, Narsim noted that the district has expended more than 2,400 hours of staff time to perform work that RMC was paid for.

“As you know, District cannot spend money to work on the tasks that were assigned to a private entity which was already paid out,” Narsim wrote. “This is gifting of public money to private entity.”

Despite these emails stating that RMC had improperly billed the water district for unperformed work, Camacho said in a follow-up interview last week that Narsim “never brought up any issues in regards to that.”

When reminded the emails she received directly from Narsim, noting the misuse of district funds, Camacho changed her story, saying that she did recall such an issue and that the matter was forwarded to district counsel Stan Yamamoto.

Camacho added, “I assume that there was a resolution, because I have not heard of any issues in regards to that, until you brought it up today.”

In a July interview, Goldie suggested he had no knowledge of RMC violating the terms of its contract or improperly billing the district. “I’m not aware of anything where RMC has billed incorrectly,” he said.

Scrutiny

Media attention to RMC’s new contract with the district has already led to a change in how contracts are being negotiated. In August, Goldie signed the single-source agreement with RMC but the deal was capped at $1.28 million, rather than the originally contemplated $4 million. Katherine Oven, a district deputy operating officer, said that the agreement was reduced by $2.7 million because of previous reports by Metro and NBC Bay Area.

“The main reason is because there’s been so much scrutiny about this contract, we decided to narrow the scope to things that are critical to inform the work of the other single-source consultants,” Oven said.

RMC senior civil engineer Steve Bui, who handled all of RMC’s watershed contracts with the district, quickly cut short a phone interview after he was asked about the billing irregularities.

Alyson Watson, RMC’s president, said she had no information about improper billings to the water district. “I am not aware of that,” she said. “That’s news to me.”

RMC is no stranger to controversy. In 2008, it was sued by an Oakland contractor over a botched dig under the Guadalupe River north of Julian St. in San Jose, in which a tunnel flooded and trapped an 11-ton microtunneling machine so deep in river mud it took two years to excavate. The city had paid RMC $683,016 for its engineering and design services. San Jose then had to write a $3 million check to settle the case and never got its new sewer line.

In reference to the Monterey County public official who was caught accepting illegal consulting payments, RMC president Watson defended the company, stating that its client, the Marina Coast Water District, asked the company to issue a consulting contract to commissioner Collins.

When the Monterey bribery scandal began to come to light, “We were asked to destroy documents, and we refused,” said a former member of RMC’s financial team. One of RMC’s name partners “asked the staff to delete a lot of documents. They refused. We refused. The documents were never deleted. We just looked at each other and said, ‘This is just weird.’ I’m not going to go to jail for anybody.”

In a 2011 wrongful termination lawsuit filed in San Diego County by former RMC accountant Karen Aquila, Aquila’s attorneys argue that “RMC did not want to jeopardize $28 million [in public contracts with the Monterey water district] by admitting to its participation in the illegalities” and feared that “RMC might be accused of participating in … criminal activities or even possibly of bribing a public official.” The now-settled complaint further alleges that RMC co-founder Lyndel Melton instructed RMC’s controller “to alter or destroy” invoices that related to “double billing” by the Monterey County official.

Steve Bui also worked on spinning the Monterey revelations, advising RMC employees “not to believe everything you read in the paper” and blaming desalinization foes “who will do anything they can to try and stop it.”

RMC had been amassing a big book of business with public agencies. “They just got money hungry, power hungry. They wanted more business. They wanted to be bigger,” the ex-employee recalled. After the problems in Monterey, “they lost a lot of business” and about 20 percent of the staff was laid off.

“We are not responsible for any of the circumstances that led to the contract being canceled, and we’ve been drawn into a dispute outside of our control,” Watson said.

After the Monterey desalinization initiative imploded, RMC had one ace in the whole—Santa Clara Valley Water District—and a new product to sell: groundwater replenishment.

Call for an Investigation

Palo Alto entrepreneur and investor Gary Kremen shook up the board after winning the most expensive water district race in history last November. Now chairman of the district’s board, Kremen remains unconvinced by the urgency argument that granted Goldie executive powers in the spring to sidestep the normal consultant qualification process.

“If you had three months to negotiate the contract, didn’t we have three months to get a bidding process started?” Kremen said. “I think it was a sham that it was supposedly so urgent. We clearly had three more months on the bidding process.”

Kremen is troubled by the reports of fraudulent billing. “I call on the District Attorney to reopen the investigation that was closed because of statute issues,” the chair said Tuesday. When informed of the refusal by the district’s CEO and legal counsel to answer questions, Kremen called for full disclosure of all RMC-related matters. “An agency in lockdown mode is not serving the public. Openness and transparency are paramount.”

“I’m more convinced now than ever that there are real internal control issues at the top,” Kremen said.

Dan Pulcrano contributed to this story.