GILROY

– Gilroy’s mayor has joined a local open space preservation

group in roundly criticizing the city’s ag preservation plans,

saying a farmland preservation bill that would protect roughly

15,000 agricultural acres just east of Gilroy

”

falls vastly short

”

of the legal requirements in the city’s General Plan.

Despite nearly unanimous approval by an 11-member task force

last month

– one member abstained from voting – the proposed policy is

triggering criticism from Save Open Space Gilroy, a local arm of

the Greenbelt Alliance which fought the city last year when it

rezoned 660 agricultural acres just east of Gilroy as industrial

land.

GILROY – Gilroy’s mayor has joined a local open space preservation group in roundly criticizing the city’s ag preservation plans, saying a farmland preservation bill that would protect roughly 15,000 agricultural acres just east of Gilroy “falls vastly short” of the legal requirements in the city’s General Plan.

Despite nearly unanimous approval by an 11-member task force last month – one member abstained from voting – the proposed policy is triggering criticism from Save Open Space Gilroy, a local arm of the Greenbelt Alliance which fought the city last year when it rezoned 660 agricultural acres just east of Gilroy as industrial land.

San Francisco-based lawyers for S.O.S. Gilroy sent a 14-page document to the city Friday lambasting the ag preservation plan. The group is pushing for a stringent acre-per-acre trade-off between developers and the city when farmland in Gilroy gets slated for urban development.

However, the task force recommended that developers mitigate for impacts to agriculture only when they develop 10 acres or more of so-called “prime farmland” and 40 acres or more of “farmland of statewide importance.”

“Common sense dictates that the conversion (from ag land to urban use) of even a small parcel of farmland can have a significant impact on an agricultural community, depending on the use and characteristics of the parcel and the surrounding area,” the group’s lawyers, Shute, Mihaly & Weinberger LLP, wrote in its letter to the city.

City Council remains split over the acre-per-acre system. Some like the idea of the more comprehensive mitigation format, while others worry that small farmland owners will be at a disadvantage when they try to develop their properties.

“I don’t want to hurt the little guy,” said City Councilman Roland Velasco.

Velasco is concerned that a farmland owner with, say, less than 10 acres who wants to develop two acres for a personal home and is willing to keep the remainder in an ag preserve would still be required to pay roughly $5,000 per developed acre.

“I don’t know if that realistically would happen under the plan, but I need more information about the plan before I can support it,” Velasco said.

The farmland protection bill, which Gilroy’s departing mayor sees as a potential legacy of his City Council tenure, will not be approved until likely the New Year – two months after Election Day when three new Council members and a one new mayor will be elected.

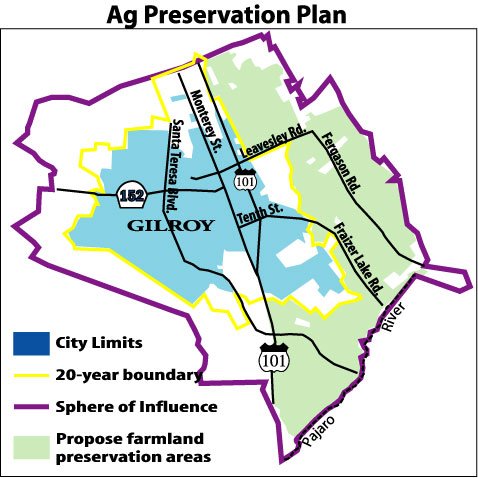

Mayor Tom Springer’s main criticism was that the policy, as drafted, would only protect farmland east of U.S. 101 outside Gilroy’s 20-year growth boundary.

By protecting only the acreage on the east, hundreds of prime ag land acres on the outskirts of Gilroy would likely be used to build homes in the future.

“If it’s prime ag land, it’s land that’s worthy of protection, regardless of where it is,” Springer said Monday at a special Council workshop.

Prime agricultural land is defined by the state as the most precious farmland acreage based on soil quality, water availability and other factors.

Under the bill, farmland owners who develop their property would be forced to mitigate for impacts to agriculture in essentially two ways.

For instance, if a developer owned two parcels of land – one in the proposed 15,000-acre protected zone east of U.S. 101 and another on farmland within Gilroy – he or she would be allowed to turn the Gilroy farmland into homes, for example, as long as they signed an agreement to keep those acres on the east as ag land forever.

In other cases, developers would be required to pay a per-acre fee to the city when farmland is urbanized (for instance, developed into housing). The city would ultimately use those fees to purchase farmland east of U.S. 101. from Masten Avenue in the north to the Pajaro River in the south.

The city would then sell the acreage to an agency, such as the Open Space Authority or Santa Clara County Land Trust. Or, the city could pay the land owner upwards of 90 percent of the land value on condition the owner gives up all development rights in perpetuity.

The mitigation policy has roots that date back to 1997, when Gilroy began updating its General Plan. During that process, the city conducted an environmental review that evaluated the impacts on Gilroy’s agriculture if farmland was rezoned for residential, commercial or industrial uses.

The city determined that a formal mitigation policy should be adopted so farmland can be preserved each time agricultural acreage gets converted into a more urban use. It formed the 11-member task force in December 2002 to hash out the details of a policy and on Sept. 10 the group forwarded its final draft in hopes of getting City Council approval.

Task force members include: City Councilmen, Planning Commission members, city staff, individuals with agricultural interests and representatives of the Open Space Authority and Santa Clara County Land Trust.

How the city should preserve open space and ag land as it continues its economic development has become a major campaign issue. City Council candidate Bruce Morasca, who is campaigning on a pro-agriculture platform, attended the Monday night session.

Morasca supported the task force’s recommendation to only

preserve farmland east of U.S. 101.

Morasca echoed the sentiments others made Monday regarding the detriments of piecemealing farmland in Gilroy limits that will eventually be surrounded by urban uses. Such a practice makes it more difficult and often more expensive to use the land agriculturally.

“It makes (the preserved land) easier to manage and to farm,” Morasca said. “Otherwise we’ll preserve farmland that’s all

piecemealed around town.”