In its 28 years, more than a million food fanatics have visited

the Gilroy Garlic Festival. Few, however, know the real story of

how South Valley became the prominent hot spot for the aromatic

herb.

Gilroy – In its 28 years, more than a million food fanatics have visited the Gilroy Garlic Festival. Few, however, know the real story of how South Valley became the prominent hot spot for the aromatic herb.

From garlic growers Don Christopher and Jimmy Hiraski to Val Filice, the festival’s much beloved “Godfather of Garlic,” many locals have helped make Gilroy the self-proclaimed Garlic Capitol of the World. But the South Valley’s Clausen family also played a pivotal – and often overlooked – role in earning the city its widely-recognized title. The Clausens helped develop the Gentry and Gilroy Foods dehydration plants that turned Gilroy into America’s garlic ground zero.

George Clausen Sr. died in 1961, but his son, George Clausen Jr. now lives in Naples, Fla., where he moved after retiring as head of Gilroy Foods in 1991. With the 29th Garlic Festival here, Clausen nostalgically recalled the saga of how his family paved the way for Gilroy’s global-wide garlic prestige.

“My mother, Lydia Clausen, and her first husband, Charles B. Gentry, founded the C. B. Gentry Chili Powder Company in Los Angeles, in 1918,” he wrote in an e-mail. “Both were active in establishing the business … As with most small start-up businesses, the company had few employees and struggled to survive.”

Charles Gentry died in the mid-1920s, and Lydia later married George E. Clausen who was a key employee at Gentry Foods’ Southern California headquarters. The couple worked hard to keep their family run spice company going through the economic devastation of the Great Depression in the 1930s.

During those difficult years, the company diversified into processing dehydrated onions and garlic, Clausen said. “There was little demand at the time but it was a companion product line for the chili powder and paprika business,” he wrote.

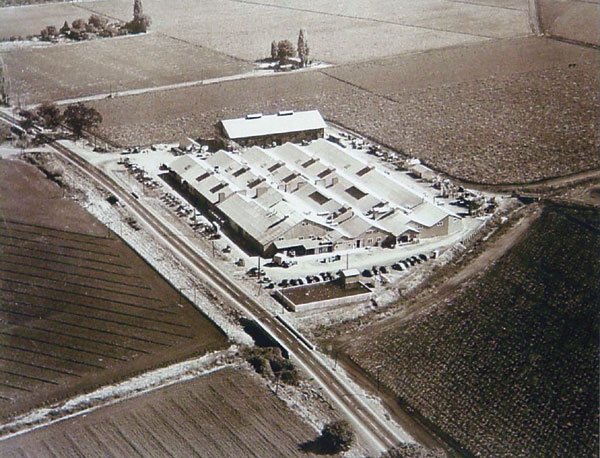

Two more attempts at dehydration plants were unsuccessful. Then in the late 1930s, Clausen Sr. met with Kiyoshi “Jimmy” Hirasaki, a Gilroy farmer who was nationally famous as “the Garlic King” for supplying much of the United States with the pungent herb. Clausen Sr. purchased a couple of acres of Hirasaki’s farm land along Pacheco Pass Road and built a small dehydration facility there.

“Jimmy Hirasaki was one of the local garlic growers with a long-term relationship with Gentry from its earliest days,” Clausen said.

Mineko Sakai, Hirasaki’s oldest daughter who still resides in Gilroy, remembers the lively negotiations between her father and the Gentry Company executive.

“Mr. Clausen wanted to build the plant in our yard, but dad said that’s too close to the house, so he sold him the street portion by Pacheco Pass,” she recalled.

With America’s entry into World War II in December 1941, the U.S. Army required a substantial supply of dehydrated foods to feed U.S. troops overseas. Military officials met with Clausen Sr. and entered into a deal to furnish processed garlic and other vegetable products.

“The Gentry Company had little resources and thus the government provided the money to construct a large facility at the Gentry site in Gilroy to produce all types of dehydrated foods, including onions, cabbage and other locally grown vegetables,” Clausen said. “Hundreds of Gilroy residents worked at Gentry 24 hours a day, seven days a week to produce food products for the Armed Services. This was mainly hand labor to prepare the raw products for processing.”

Gentry’s Gilroy plant did such an excellent job in helping with the war effort that the firm received several government awards including the Army-Navy E Award for excellence, Clausen said.

With the end of the war in 1945, however, Gentry found it had a large processing plant, built at government expense, but with little consumer demand for its dehydrated garlic product. The company faced dire financial difficulties and was forced to lay off many of its workers. It struggled for the rest of the decade and was sold in 1951 to Consolidated Foods of Chicago (which is now Sara Lee Corp.).

“My father retired from Gentry shortly thereafter in poor health,” Clausen said.

In 1958, Gentry faced competition from a small start-up company called Gilroy Foods. It was started by Mario DeFransesco, a former employee of Gentry, and a group of 15 Gilroy garlic growers and businessmen, Clausen said. Among the early investors were well-known Gilroy residents Bruce Jacobs, Sig Sanchez, Tom Obata and Joe Mondelli. They built the new dehydration plant on 2.5-acres of land next to Gentry’s facility.

Don Christopher said he wasn’t among the original 15 initial investors but was in a second group of 10 local business people asked to invest $10,000 each in Gilroy Foods.

“There was a very good chance after we put our money in that they were going to go broke,” he said of that investment. “It was a gamble, but really we wanted Gilroy Foods to make it because it would be good for the whole industry to make it strong.”

After working for Gentry for five years, Clausen Jr. left in 1957 to move to Mexico, with his wife Sharon and their two children, to start his own dehydration company. When that business venture proved unsuccessful, he and his family returned to California in 1959 and Clausen joined Gilroy Foods as an investor. The next year, company officials appointed him as president. In its first year of production, it processed more garlic than there was demand for in the American market.

“After a few months, the Gilroy Foods Board and investors decided the company had to be sold in order to survive,,” he recalled. In early 1961, he traveled to the Baltimore, M.D.-based firm of McCormick & Co. to see if that firm would buy Gilroy Foods. Clausen convinced McCormick to acquire the company, and he stayed on as president. Significant to Gilroy Foods’ survival, McCormick provided its new subsidiary with quality management and technical assessment and poured money into modernizing the dehydration equipment, he said.

“Thanks to McCormick, nobody lost any money in the startup,” Clausen said.

Christopher said initial investors were paid in stock which went up in value as Gilroy Foods grew successful over the years. “It went up five or 10 times,” he said. “We were very, very lucky.”

During the 1950s and 1960s, an international market for chili powder, paprika, onion and garlic seasoning products exploded, Clausen said. Consolidated Foods invested money in upgrading the Gentry Gilroy facility, and the company over time grew into an important employer in the South Valley.

“Many local Gilroy residents worked at Gentry during these early development years,” Clausen recalls.

In the 1970s, Consolidated Foods sold Gentry Company to an independent investment group which managed it until the late 1980s. At the end of that decade, Gentry was purchased by Gilroy Foods. After 29 years at Gilroy Foods, Clausen retired.

The dehydration plant is now owned and operated by Omaha, Neb.-based ConAgra Foods Inc., one of North America’s largest food processing companies.

Clausen is proud of his family’s involvement with making Gilroy the premier garlic processing site it now is. The spice company his mother and C. B. Gentry started 89 years ago set in motion the chain of events that built the garlic industry in South Valley. This led former Gavilan Community College President Rudy Melone to suggest at a 1978 Gilroy Rotary Club meeting his “crazy” idea for a festival focused on garlic-cooked cuisine.

Clausen said he’s pleased the Gilroy Garlic Festival has given back so much to the South Valley community – with more than $7.5 million provided to charity organizations over the years. He’s also pleased at how his experience at Gilroy Foods helped in making the community the Garlic Capitol of the World.

“If I could do my career over again, I’d go back and do it all over again,” he said. “How many people can say that?”