When Toby Valdivia of Morgan Hill was growing up, pigeons were

always present.

”

My grandparents used to have a huge house

– a hacienda – and they had a lot of birds there,

”

said Valdivia.

”

My aunts used to kill a couple of them every once and a while,

and we’d eat them. I always liked them for some reason, so they

gave me a couple of pairs of babies.

”

When Toby Valdivia of Morgan Hill was growing up, pigeons were always present.

“My grandparents used to have a huge house – a hacienda – and they had a lot of birds there,” said Valdivia. “My aunts used to kill a couple of them every once and a while, and we’d eat them. I always liked them for some reason, so they gave me a couple of pairs of babies.”

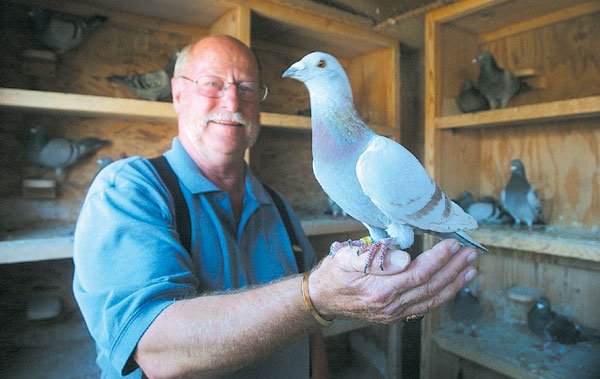

Today, Valdivia has more than 400 birds, which he breeds and races across the western United States for cash prizes.

Homing pigeons, which have been used as message transporters since the year 1150, are a domesticated variety of Rock Dove. Used as message transporters in Europe and the United States through World War II, they were more recently retired from such work in other areas of the world (see box). Today, enthusiasts race their pigeons, with birds trucked hundreds of miles away for a single race. Many times the competitions are for cash prizes.

“You band a bird when it’s seven days old, and it’s named,” said pigeon enthusiast Bob Littlejohn of Gilroy. “These days, we put a computer chip in a band on the opposite leg. Then, when we take them to a race, they just input the chip number, and it activates a timer that can measure flight time down to a hundredth of a second.”

Littlejohn and his racing partner’s combined bird stock is about 400 cocks and hens, all of which are segregated by sex in large, divided coops outfitted with one-way doors.

As he releases the outbound door of one cage, a cooing group of hens flutters to life, churning the air with a strong breeze produced by the furious flap of their wings. Up close, they sound like the whining of a car that won’t start.

The pigeon-racing season, which started nearly two weeks ago, runs for three months, with young and old birds competing in separate categories.

Individual owners take their hatchlings and train them to fly home, releasing them from points farther and farther from the home base, said Littlejohn. Then, races begin to build the birds’ stamina.

At the beginning of the racing season, a young bird may fly just 120 miles, but by the end of the season they’ll be cruising to nearly 600.

“This year I’ll race 50 of the birds,” said Valdivia. “I have about 200 of them that are breeders, and I mate them according to what I’m looking for. If I want a long-distance bird, I’ll breed two long-distance birds, but I’m also looking for body shape.”

Valdivia likes his birds football shaped, with a strong chest and a bit of tail muscle for balance and support.

“If they have a really weak back, they may be able to fly 200 miles, but they’re not going to make it 400,” Valdivia said.

Pigeon races, the largest of which can include pots of $1 million to $6 million, are really won and lost at two key moments, though, said Littlejohn.

“The winning ones very seldom come in a big group,” said Littlejohn, who began racing pigeons in the early 1970s. “The one that wins the prizes usually will break from the rest and be out front. If he can keep straight home and keep his speed, he’ll win. If he lets up, another bird can finish strong and win it.”

The electronic tags that birds are now fitted with are read by a scanner at each member’s home, noting time and global position. GPS is used to determine exactly how far each bird has traveled, adjusting times to reflect a single distance rather than shorter and longer hops.

“In the old days, you could beat birds by 15 minutes,” said Littlejohn. “But the breeding now is so strong, if you can get ’em by 15 seconds, you’re pretty lucky..”

Depending on weather and winds, a pigeon can fly anywhere from 1,300 to 2,000 yards per minute, said Valdivia, who recently saw a rise in his birds’ flight times as he switched from a southern to an eastern flight group.

“Coming from the north, it was easier because the wind was in their favor,” he said. “This year, the birds get a lot of head wind, so they can’t go as fast.”

Birds, the finest of which can trace blood lines back hundreds of years and sell for $5,000 each, can also, on rare occasions, become lost.

“If you overcrowd a loft, they’ll fly off because they’re unhappy, or sometimes a whole group will just not come back,” said Littlejohn. “Sometimes they get lost. Sometimes they get stolen, but I think we’d get a lot more interest if we had a tracking system like they do for dogs.

“I’ve lost some birds that I’d like to know where the hell they went. And if they got stolen, it would be a little hard to say they were yours if I came knocking on your door with my GPS.”

Most specialty birds don’t know how to survive in the wild, said Valdivia.

“They’re not like the regular pigeons that try to pick up food in the grocery store parking lot,” he said. “They’re used to having an easy lunch on top of the table.”

A good pigeon can be raced five to seven years, said Valdivia, but if he runs across a solid performer, it will be more likely to wind up in the breeding coops.

“If I have a pigeon who flies really well and is really consistent, especially if he’s a winner, he’s going back,” said Valdivia. “If you have the parents, a lot of times you might chance it more. You can always breed another one like that, but you can also use the winner to breed a whole lot more.”