GILROY

– The 20 to 30 mountain lions a local game warden estimates live

in this county are more likely to see you than you are to see them.

Rather than a cause for alarm, that could be a comfort.

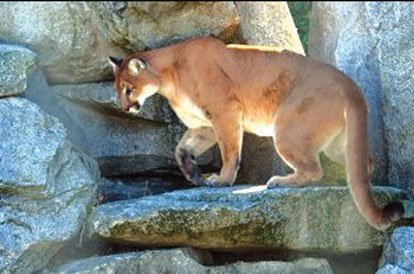

GILROY – The 20 to 30 mountain lions a local game warden estimates live in this county are more likely to see you than you are to see them. Rather than a cause for alarm, that could be a comfort.

“(The vast majority) of the time, the cats are more wary of us than we are of them,” said Game Warden John Nores, who covers southern Santa Clara County for the state Department of Fish and Game. “Cats really don’t want to interact with people. They want to avoid people.”

It is extremely rare for cougars to prey on humans, but attacks have happened. When they do, they grip the public imagination, striking trepidation or even dread in many people who enter the hills and countryside outside of Gilroy and Morgan Hill. The most recent fuel to the fear came from a large puma that attacked two cyclists separately on Jan. 8 in Orange County, killing and partially eating one and critically injuring the other.

The number of cougar sighting reports spikes after such an incident, game wardens say. Conversely, wardens issue a round of assurances and reminders about how uncommon attacks actually are. One is more likely to die from a lightning strike than a puma attack, according to a Fish and Game Department brochure called “Living with California Mountain Lions.”

In the 114 years since mountain lion attacks have been recorded in California, there has been just one in Santa Clara County – 95 years ago in Morgan Hill.

In 1909, a rabid cougar attacked young Earl Wilson, who was swimming in Coyote Creek with his Sunday school class. The teacher, 38-year-old Isole Kennedy, fought off the animal with a stick and a hat pin while her students fetched John Conlan, a surveyor working nearby. Though Conlan shot the animal with a shotgun and hit it with the butt, it reportedly paid no attention and continued to attack Kennedy, who continued to fight back. Conlan ran home, got his rifle and shells, returned and shot the cat once each in the shoulder and mouth, finally killing it. Kennedy and Wilson survived their wounds but were infected with rabies, which they died of shortly afterward. (From the book, “Under the Shadow of El Toro,” compiled by Joyce Hunter)

This was the second recorded cougar attack in California history. The next came 77 years later, in 1986. There have been 13 statewide: 10 in Southern California and one each in this, Mendocino and Siskiyou counties. Six of these victims died.

Not only have puma-human attacks risen in the past two decades, but human sightings of the cats have also increased in frequency, according to the Fish and Game Department. In “Living with California Mountain Lions,” the department cites the following explanations:

• More people moving into cougar habitat

• An increase in prey populations

• An increase in cougar numbers and expanded range

• More people using trails in cougar habitat

• Greater public awareness of cougars’ presence.

Fish and Game Lt. Dave Fox, based in Monterey, said he believes the regional cougar population has grown since they became a protected species in 1990, when California voters banned hunting them. Until 1963, the state offered people a cash bounty for every cougar killed.

Nores figured there are probably 20 to 30 mountain lions living in Santa Clara County. He said there are 10 to 20 confirmed mountain lion sightings a year in the county out of 100 or more reported sightings, most of which are bobcats or other animals. Two or three cougars are hit by cars a year in this county, as a 100-pound female was on Jan. 23 on Watsonville Road, northeast of Gilroy.

Although South County is more rural than the northern half, that doesn’t necessarily mean there are more cougars here.

“We may have just as many mountain lions in the Mount Hamilton range and the Los Gatos range, on the edges of the cities,” Nores said.

The Fish and Game Department estimates there are now roughly 5,000 mountain lions in California, but no count has been done in many years.

If any local cougar decides to make another go at a human, locals would do well to imitate Kennedy’s bravery if they want to save their skins, according to the Department of Fish and Game.

If you encounter a cougar, “Living with California Mountain Lions” recommends that you not approach it but not run away either, as fleeing could “stimulate the mountain lion’s instinct to chase.” In general, do everything you can to convince the lion that you are not prey and could actually be a danger to it.

Do not crouch down or bend over but instead raise your arms and open your jacket to appear larger. Throw stones or branches if you can do so without crouching or turning your back on the cougar.

And like Kennedy, fight back if attacked. The department says people have successfully defended themselves and others against cougar attacks.

To avoid meeting a mountain lion, the department recommends hiking in groups of two or more and making noise as you go. As long as the cat knows where you are, it will likely avoid you.

“A lot of times we don’t see them, but that doesn’t mean they’re not there,” Fox said.

Cougars may not be lurking too far from trails. According to a University of California at Davis study released Jan. 20, cougars wearing radio collars in San Diego County typically concealed themselves during the day in dense vegetation within 100 to 300 meters of a trail. They usually set off to hunt at about 90 minutes before dusk and continued to do so until about 90 minutes after dawn.

A male cougar’s hunting range can be 100 square miles, depending on the availability of prey. In the Santa Cruz Mountains, this range is usually smaller due to abundant deer – the main staple of cougars’ diet – and wild pigs, Fox said.

Cougars also kill and eat livestock, such as goats, sheep and chickens – and sometimes personal pets – and game wardens recommend owners keep their animals inside a barn or other structure at night. It is in looking for such prey that cougars are often seen on urban fringes, Nores and Fox said.