Ah, the smoky, spicy and sweet smells of Memorial Day. You’ve

got your chicken, ribs, potato salad, watermelon, baked beans and

peach cobbler. Delicious, sure, but how far did your food travel

before it ended up on your backyard grill?

Ah, the smoky, spicy and sweet smells of Memorial Day. You’ve got your chicken, ribs, potato salad, watermelon, baked beans and peach cobbler. Delicious, sure, but how far did your food travel before it ended up on your backyard grill?

If it came from a typical grocery store, chances are the answer is “pretty far.” And, along the way, the fare likely was exposed to a host of things you never meant to consume, such as smog from the food’s freeway journey.

Along with being healthier for you and the environment, buying fruits and vegetables that have been farmed nearby supports local farmers and economies. Besides, local produce often means tastier produce – which might encourage you to eat more of what you’re supposed to be getting five of a day.

Most produce – even organic – in the United States is picked four to seven days before being placed on supermarket shelves, according to LocalHarvest, a Santa Cruz-based online database of organic farms across the country.

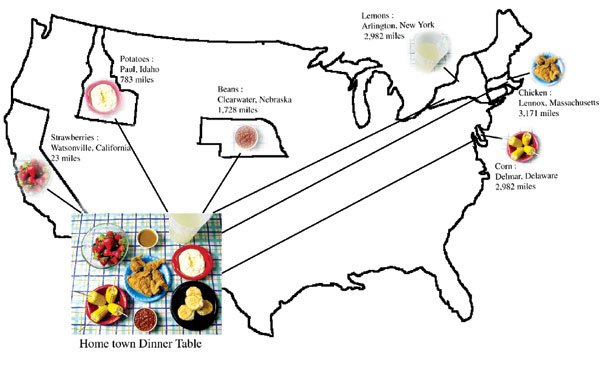

Additionally, an average of 1,500 miles separates most fruits and vegetables from their origin to the shelves where they will be sold.

And that’s just produce grown in the United States – consider the distance mangoes from Mexico, mixed greens from Switzerland and passion fruit from Argentina have to travel before reaching supermarket shelves here.

Although the health consequences of eating produce grown afar are minimal, they are real, said Jennifer Zapata, dietary director for Hazel Hawkins Convalescent Hospital.

Like human skin, fruits and vegetables have pores on their surfaces, which means they absorb minuscule particles from the surrounding air. On a congested freeway, that means pollution and dirt. On an inorganic farm, that means pesticides and harmful fertilizers.

“Produce that is not local has probably been exposed to longer periods of sunlight, and the longer things sit in transit, the more they’re going to be exposed to the factors of the environment,” Zapata said.

Environmental factors are nearly impossible to taste when eating the produce, Zapata said. Even so, the pollutants can dull the flavor, as can picking produce before it ripens – which might cause some people unknowingly to shy away from getting their fill.

“Flavor adds pleasure to eating. Nowadays, we’re trying to encourage people to eat a lot of fruits and vegetables and get a lot of fiber,” she said. “But to be honest, a lot of fruits and vegetables you get at the grocery store don’t have a lot of flavor. There’s such a difference when you get a tomato from a neighbor or a farmers’ market. The flavor is so intense.”

More intense flavor is one reason Nancy Gammons, owner of Four Sisters Farm in Aromas, farms organic and encourages others to buy local.

On her five-acre farm, Gammons raises cut flowers, kiwis, avocados, apples, herbs and specialty vegetables. Also a manager of a Watsonville farmers’ market, Gammons believes local produce packs a punch both in flavor and health.

“Once any plant is cut – you see it more in flowers, but it’s true for vegetables, too – they lose their life and they start to die,” she said. “Life exists of vitamins, and when plants lose their lives, they lose their vitamins. There’s really no point in eating vegetables unless the nutrients are there.”

Along with being better for the body, buying local produce often is more economical.

The price of food bought in most grocery stores reflects not only the cost of the produce, but also gas for the truck, the driver’s salary and profit for the grocery store.

“People often think produce bought at farmers’ markets is so expensive,” Gammons said. “But in reality, when you buy at a farmers’ market, you’re actually paying for the food, and the money is going to the farmer.”

Short of raising cattle, chickens and pigs in your backyard, finding meat that is raised nearby usually is more difficult than finding local produce.

But there are several ranchers in Northern California who raise grass-fed, hormone-free cattle, such as Chileno Valley Natural Beef in Petaluma and the T.O. Cattle Co. in San Juan Bautista.

Unlike fruits and vegetables, shipping meat for days – as long as it’s refrigerated or frozen – doesn’t undermine its nutritional value.

Pasture-raised animal products, however, have certain nutritional advantages over traditionally farmed meat, such as having a lower fat content and higher content of omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin E and beta carotene, according to Joe Morris, co-owner of T.O. Cattle Co.

Raising animals on pastures instead of in confinement also is better for the ecosystem.

Ranchers in the grass-fed market tend to be more aware of taking care of the land, using grazing techniques that sustain pastures.

Grass-fed beef is more expensive than the typical beef found at most supermarkets, and it’s also seasonal, available only in the late spring and early summer.

However, grass-fed beef freezes well, and it can be purchased in bulk and frozen in parcels to last through the year.

To encourage more Californians to buy local, in 2002 the state kicked off the California Grown campaign, which includes radio, TV and billboard advertisements highlighting the benefits of supporting California-made products.

More than two dozen agricultural organizations are aboard the campaign, which also coordinates with local grocery stores to supply more California-grown products.

According to a 2003 study released by the campaign’s primary funding source, the Buy California Marketing Agreement, if all California consumers were to choose locally grown produce for their barbecues, farms would receive $76.2 million in revenue and farmers would spend $65.4 million to meet the demand.

Enjoy your Memorial Day meal. But next time, perhaps consider the origin of your food.

How can I buy local?

Buying local doesn’t necessitate scouring the region for products grown nearby. While at the grocery store, check produce for California Grown labels.

If you don’t see them, examine the produce for other stickers that at least will identify the country of origin as mandated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. State-of-origin labeling is not required by law, but occasionally, that information will be included as well.

For more information about the California Grown campaign, call (916) 651-7384 or visit www.californiagrown.org. The Web site also provides several recipes for California-grown dishes.

For even more confidence you’re buying local, visit some farmers’ markets, which are plentiful in and around the South Valley:

Felton: St. John’s Church at Russell Avenue and Highway 9. Tuesdays, 2:30 to 6pm, May to November.

Hollister: Downtown at 400 San Benito St. Saturdays, 4 to 8pm, May to October.

Morgan Hill: Downtown train station at Third and Depot streets. Saturdays, 9am to 1pm, year-round.

Salinas/Alisal: East Alisal and Pearl streets. Mondays, 9am to 6pm, May to November.

Salinas/Northridge: Northridge Mall parking lot, 796 Main St. Sundays, 8am to noon, March to December.

San Jose/Blossom Hill: Princeton Plaza Mall, northwest corner of Kooser Road and Meridian Avenue. Sundays, 10am to 2pm, January to November.

San Jose/downtown: San Pedro Square between Santa Clara and St. John streets. Fridays, 10am to 2pm, May to Dec. 16.

San Jose/Kaiser-Santa Teresa: 250 Hospital Parkway off Highway 85. Fridays, 10am to 2pm, year-round.

Watsonville: Peck Street between Main and Union streets at the Plaza. Fridays, 3 to 7pm, year-round.

Additionally, several farms in the area are open daily and offer product samplings and purchases. Check your local phone book for listings.

Source: www.cafarmersmkts.com, www.cafarmersmarkets.com