Gilroy students are dropping out at a faster pace than county

and state students, according to data provided by the California

Department of Education.

Gilroy students are dropping out at a faster pace than county and state students, according to data provided by the California Department of Education.

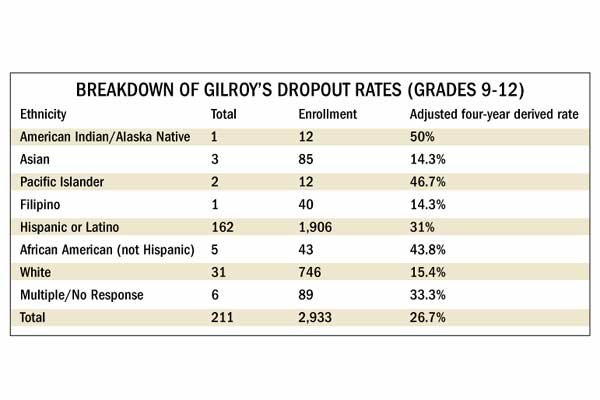

Based on one year of data, Gilroy’s high school four-year estimated dropout rate is 26.7 percent, higher than both the county and state rates of 20.2 percent and 24.2 percent, respectively.

State Superintendent of Public Instruction Jack O’Connell held a news conference Wednesday afternoon at Birmingham High School in Van Nuys to release the 2008 report on California’s dropout and graduation rates. For the first time, the rates were collected and reported based on individual student-level data, which provides much more accurate information about how many students are or are not completing their education.

According to the data, 7.2 percent of high school students in the Gilroy Unified School District did not complete their education in the 2006/07 school year. Using that number, the CDE extrapolated over four years, and derived a four-year dropout rate of 26.7 percent, the second highest rate in the county trailing only East Side Union High District, according to the Santa Clara County Office of Education.

“I’d like to stress that these numbers are all new,” said Assistant Superintendent of Educational Services Basha Millhollen. “We have yet to address the clean-up of the data. We have to make sure dropouts are true dropouts and that they didn’t re-enroll somewhere else.”

Unlike many other districts, GUSD didn’t have a chance to “clean-up” its data in June due to shortstaffing, Millhollen said. Students that may have migrated to an alternative school, moved out of town or left school to pursue different educational opportunities are initially coded as “dropouts.” The district is given the opportunity to send for each student’s records to determine whether or not they did, in fact, drop out.

“These numbers are just preliminary,” Millhollen said. Optimistic that the numbers would reflect a more positive outlook after cleaning up the data, she said her staff will begin their analysis in the coming weeks. “We believe we will be in range after the clean-up.”

Of the surrounding high school districts, Gilroy’s data most similarly reflected Pajaro Valley Unified’s (Watsonville) four-year dropout rate of 22.3 percent. Morgan Hill’s and San Benito’s were significantly lower at 14.5 percent and 13.6 percent, respectively.

The data shows educators and administrators “have much work to do in the area of dropout prevention, especially for Hispanic students and students of poverty,” County Superintendent Charles Weis said. “The Santa Clara County Office of Education is prepared to evaluate the alternative education programs operated by the SCCOE in order to determine their effects on students who are at high-risk of dropping out, and to do whatever we can to assist our school districts in evaluating their dropout prevention programs. Our goal is to bring best practices for preventing dropouts to all of our schools in Santa Clara County.”

“This is a very serious issue,” said Board President Rhoda Bress. “First of all, it’s not like these figures took me by surprise. We know this is an issue that we’ve been working on for some time.”

However, Bress said she would have expected numbers that reflected an even higher dropout rate had the district not implemented certain programs like Advanced Path and after-school tutoring, aimed to keep at-risk students in school.

“I think these figures would have been even worse if we hadn’t already made an effort,” she said.

“This is not a new situation we’re finding out about by opening up the paper,” she continued. “We have certainly not ignored this issue. It’s not a good figure and there’s obviously work to be done. It’s been an agenda item in the past and needs to be again.”

Students were most likely to drop out in their senior year, a trend that held true statewide, countywide and in surrounding districts.

“Students who can’t pass the CAHSEE tend not to stay in the system,” Millhollen said of the California High School Exit Examination. “They might migrate to an alternative school. If a student thinks they may not graduate, they start looking for different avenues.”

Having spent several years teaching at-risk high school students, Millhollen noticed students deciding to leave during the last year of their education.

“The 11th grade is when they make the decision and 12th is when they just don’t come back,” she said.

With data in hand, the district is armed to tackle the problem head on. Districts have one more opportunity to make data corrections before the report is finalized.

“We now need to go in and figure out what is happening with whom,” she said. “What can we do.”

Optimistic that the numbers will more closely reflect the state rate after getting more accurate data, Millhollen was still unhappy with the amount of dropouts statewide.

“That’s still a big number,” she said of the 87,456 high schoolers that dropped out of school across the state during the 2006/07 school year. “We want it to be zero.”