Gilroy

– It will come as no surprise that turkeys, being neither big of

brain nor charming of countenance, often need a little help with

their love lives. Too busy strutting around in macho confused male

flocks, jakes, as they’re known, sometimes don’t bother mating

until a hunter comes along and frighte

ns the mood into them.

Gilroy – It will come as no surprise that turkeys, being neither big of brain nor charming of countenance, often need a little help with their love lives. Too busy strutting around in macho confused male flocks, jakes, as they’re known, sometimes don’t bother mating until a hunter comes along and frightens the mood into them.

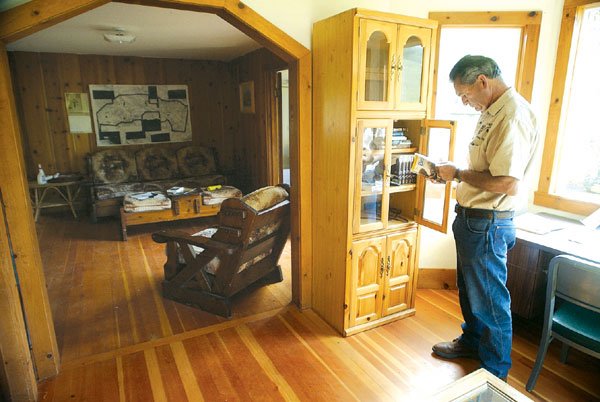

“When you shoot at a gobbler, the birds will disperse and they’re more apt to find a hen and mate,” said Henry Coletto, former Santa Clara County Fish and Game Warden. “A turkey has a brain about the size of a pea, but they have fantastic eyesight and hearing. It looks like they’re very easy to hunt but once they catch sight of you or hear you, they’ll take off.”

Turkeys can be hunted in the spring and fall, but during mating season it’s only legal to take gobblers. That will be one of the first lessons Coletto gives to the five lucky junior hunters he takes turkey hunting later this month as part of a youth education program at the Cañada de los Osos Ecological Reserve. Between now and November, Coletto will lead six groups of young hunters after turkeys, pigs, doves and deer.

“Kids don’t have hunting and fishing opportunities,” Coletto said recently. “I really believe the rural atmosphere is gone. Kids spend most of their time in front of the TV. They walk into a supermarket with their mom and dad and don’t know where a chicken or a pork chop comes from.”

The reserve, 44 acres of land east of Gilroy and south of Henry W. Coe State Park, is owned by the California Department of Fish Game.

It’s the only one in the state set aside primarily for educational hunting trips for youth. It is managed by Coletto and the California Deer Association, which spends about $25,000 a year and hundreds of volunteer hours for habitat projects and educational outings.

Before kids get to take aim at their prey, they must learn all about their prey. The hunts are two-day affairs, with the first day devoted largely to studying the animals and their habitats.

The junior hunters learn how to help the species thrive and how to protect them against disease and the dangers of man.

Jeannine DeWald, a wildlife biologist with the DFG, said that Coletto is the best man to lead the hunts because after 35 years as fish and game warden he knows as much about area wildlife as anyone.

“There’s a lot of kids who would like to learn more about hunting, and this is more of an educational experience than going out with dad or an uncle,” DeWald said. “The kids go out with experienced guides who can teach them a lot.”

Coletto is sensitive to criticism from people who see hunting as nothing more than cruel sport. To him, hunting is part of sound wildlife management. There are strict limits on the number of animals that can be killed, and any that are downed become teaching tools.

The junior hunters learn to dress out and skin animals. They learn where different cuts of meat come from. Coletto and his team of wildlife experts take blood and tissue samples, and check for parasites and diseases that may be bothering the population. Deer at the reserve are at risk for the deadly blue-tongue virus, which induces a debilitating fever and causes the deer to stop eating.

“We do a complete necropsy,” Coletto said. “We’re taking an animal, but we’re also getting a history of diseases that might affect the deer herd. Hunting is a component of wildlife management and education and gives the kids a more well-rounded understanding of nature.”

The hunts are very popular. DFG received more than 200 applications for the three hunts it sponsored last fall (each hunt consists of four to six kids). DeWald said dozens of applications have already poured in this year.

Like Knox Buciak, 13, of Morgan Hill, who hunted turkey with Coletto last fall, most of the participants are first-time hunters.

“It was a lot of fun, I couldn’t believe I was drawn for it,” Buciak said. “I had a blast.”

Buciak bagged a turkey as a flock of them tried to flurry away.

“There were a whole flock of them and they started going up a hill,” Buciak remembered. “A bunch of them got through a fence and I got one right as he was going through it.”

Coletto said that kids he takes on hunts often feel like they’ve been transported hundreds of miles from civilization.

“You take a kid up here who’s 10 to 15 years old and they think they’re in the wilderness,” Coletto said. “But once they settle in they have a much better appreciation of what’s going on.”

Three years ago, the reserve was a denuded cattle ranch that had been overgrazed and infested with nonnative grass species that are useless to wildlife and livestock. Under Coletto’s stewardship, the land has rebounded.

Nettlesome Medusa-head grass and purple hemlock is giving way to nutritious buttercups and buckeye trees. Elderberry bushes are beginning to flourish again.

Coletto has big dreams for the reserve. One of his first projects is to restore flora that attracts animals to feed and bathe in area streams and riparian corridors.

He’s trying to secure a grant to rehabilitate the creek that runs through the park and has fenced off a natural spring to study the habitat of the endangered California red-legged frog.

Piles of brush arranged near the spring provide cover for quails, who can make the short hop to the spring, safe from the hawks looking for a slow-moving meal.

Coletto’s grandest vision is of an education and research center at the reserve, complete with library, computer center and working laboratory. At the moment he’s a few million dollars short of that goal.

“We’re talking several million dollars to put that facility in. We don’t have that kind of money so we’ll be looking for outside donations and grants to make that happen,” he said. “In the next year or two that’s where I’ll be spending my energy.”

To make a donation or for more information about the Cañada de los Osos Ecological Reserve, visit the California Deer Association at www.caldeer.com.

Attending a hunt

Hunt Dates Deadline

Spring pig May 28-29 April 28

Dove Sept. 3 Aug. 3

Deer Sept. 10-11 Aug. 10

Fall pig Oct. 15-16 Sept. 15

Fall turkey Nov. 12-13 Oct. 12

To apply to attend a junior hunt in Cañada de los Osos Ecological Reserve, send a postcard with name, address, phone number and 2004-2005 junior hunting license number to:

California Department of Fish & Game

20 Lower Ragsdale Road

Monterey, CA 93940

The post card needs to state clearly which hunt the application is for. Space is very limited and entries are chosen at random.