Set aside differences in reaching compromise in legislation that

could give U.S. citizenship to 11 million illegals

By David Espo, AP Special Correspondent

Washington – Putting aside party differences, Senate Republicans and Democrats coalesced Thursday around compromise legislation that holds out the hope of citizenship to an estimated 11 million immigrants living in the United States unlawfully.

“We can no longer afford to delay reform,” said Republican Sens. John McCain and Edward M. Kennedy in a statement that capped weeks of struggle to find common ground.

President Bush said he was pleased with the developments and urged the Senate to pass legislation by week’s end.

But the emerging compromise drew fire from both ends of the political spectrum. Conservative Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, likened it to an amnesty bill that cleared Congress in 1986, while AFL-CIO President John Sweeney said it threatened to “drive millions of hardworking immigrants further into the shadows of American society, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation.”

Still, after days of partisan, election-year rancor, an overnight breakthrough on the future of illegal immigrants propelled the Senate closer to passage of the most sweeping immigration legislation in two decades.

In an indication of the complicated political forces at work, officials of both parties disagreed about which side had blinked. But they agreed that a decision to reduce the number of future temporary workers allowed into the country had broken a deadlock that threatened as late as Wednesday night to scuttle efforts to pass a bill. The change will limit temporary work permits to 325,000 a year, down from 400,000 in earlier versions of the bill.

Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist, R-Tenn., characterized the developments as a “huge breakthrough.” Senate Democratic leader Harry Reid of Nevada said he was optimistic about final passage, but cautioned, “We can’t declare victory.”

Sen. Arlen Specter, R-Pa., chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, said: “While it admittedly is not perfect, the choice we have to make is whether it is better than no bill, and the choice is decisive.”

Officials described a complex series of provisions:

– Illegal immigrants who have been in the country for at least five years could receive legal status after meeting several conditions, including payment of a $2,000 fines and any back taxes, clearing a background check and learning English. After six more years, they could apply for citizenship without having to leave the United States.

– Illegal immigrants in the country for between two and five years could obtain a temporary work visa after reporting to a border point of entry. Aides referred to this as “touch base and return,” since people covered would know in advance they would be readmitted to the United States.

– Officials said it could take as long as 13 to 14 years for some illegal immigrants to gain citizenship. It part, that stems from an annual limit of 450,000 on green cards, which confer legal permanent residency and are a precursor to citizenship status.

– Illegal immigrants in the United States for less than two years would be required to leave the country and apply for re-entry alongside anyone else seeking to emigrate.

Separately, the legislation provides a new program for 1.5 million temporary agriculture industry workers over five years.

It also includes provisions for employers to verify the legal status of workers they hire, but it was not clear what sanctions, if any, would apply to violators.

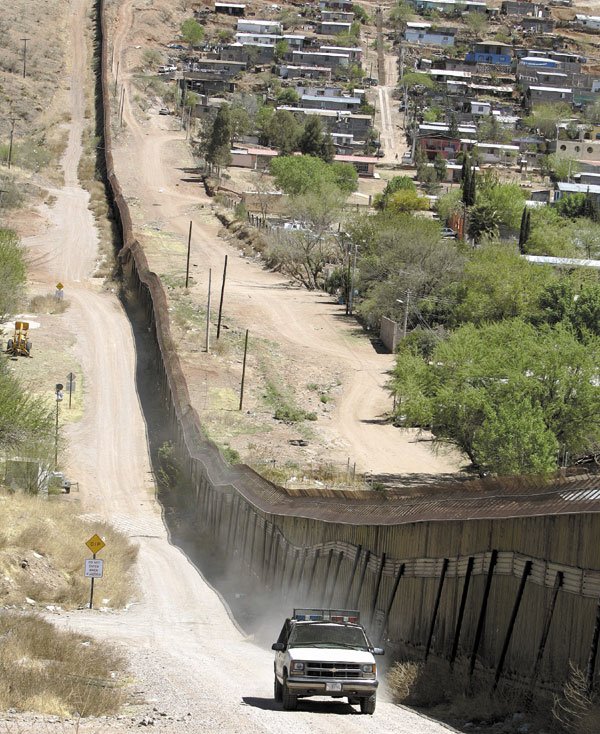

To secure the border, the bill calls for a virtual fence – as opposed to the literal barrier contained in House legislation – consisting of surveillance cameras, sensors and other monitoring equipment along the long, porous border with Mexico.

Conservatives unhappy with the deal voiced their concerns to Frist, while Democrats sought assurances that the agreement would not be undercut in any future compromise talks with the House. McCain told reporters that he and other members of the GOP were circulating a letter pledging to vote against any changes demanded by the House that “would destroy this very delicately crafted compromise.”

The House has passed legislation limited to border security, but Speaker Dennis Hastert, R-Ill., and other leaders have signaled their willingness in recent days to broaden the bill in compromise talks with the House.

The comments sparked a furious counterattack from critics.

“I can just about guarantee you we’re not going to get a majority of the House members (to agree) on amnesty to 10 million people,” Rep. Tom Tancredo, R-Colo., said at a news conference. “I am disappointed that apparently Mr. Frist has caved in to the desires of Democrats, to Kennedy,” he added.

Tancredo’s remarks underscored the unpredictable political fallout from the issue as Republicans seek legislation to fortify the borders without offending the fast-growing Hispanic voting population. Bush has long argued that a guest worker program is an essential element of border security, but potential challengers for the 2008 GOP nomination have come at the issue from a variety of perspectives.

McCain and Kennedy have worked hard to find common ground, and Sen. Sam Brownback, R-Kan., supported a bipartisan measure that emerged from the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Frist, a potential presidential candidate in 2008, sought to establish more conservative credentials when he initially backed a bill limited to border security, an approach that drew criticism from some members of the rank and file who said he was placing his own ambitions ahead of the party’s interest. At the same time, Frist has repeatedly called for a comprehensive bill – adopting Bush’s rhetoric – and involved himself in the fitful negotiations over the past several days.