The Gilroy Yamato Hot Springs lies out of sight amid steep, earthy embankments and lush wilderness hillsides, but plans are afoot for this ghostly shell of an aging 18th century jewel tucked away off Roop Road in the mountainous sanctuary of Henry W. Coe State Park, roughly 17 miles southeast of downtown Morgan Hill.

“We have some wonderful new energy behind a lot of good things happening,” said Laura Dominguez-Yon, whose family resided at the Gilroy Hot Springs resort from 1945 to 1955.

As founder of the Friends of Gilroy Hot Springs, an advocacy group formed five years ago, Dominguez-Yon is leading the charge for the landmark’s rebirth in the 21st century.

She wants to remind the public about the Jan. 12 forum, which will give locals a chance to cast their two cents concerning the springs’ future. The meeting will be held from 6:30 to 8:30 p.m. inside the El Toro Room at the Morgan Hill Community and Cultural Center, located at 17000 Monterey St.

According to a news release from the California Department of Parks and Recreation, Henry W. Coe State Park is conducting an initial assessment to make recommendations for a viable management plan to “restore public access to Gilroy Yamato Hot Springs and pursue potential revenue opportunities to help financially support the park.”

Dominguez-Yon elaborated the purpose of the meeting is to write a master interpretive plan. The current plan is 20 years old and needs to be updated, she said.

“Basically it’s a wishes and hopes list,” she said. “So now is the time for people to let their hopes be heard.”

Getting an idea added to the master plan doesn’t ensure it will come to fruition or be implemented right away, she added, “but it does mean that we at least thought of it.”

The pristine oasis on the National Register of Historic Places that opened in 1866 has experienced a fluctuating relationship with the public, from a choice escape for the high-profile and elite, to post-World War II hostel for resettling Japanese, to haven of homeopathic healing where relief from ailments was sought, to popular family retreat in the 1950s to a decaying landmark nestled in the recesses of isolated overgrowth.

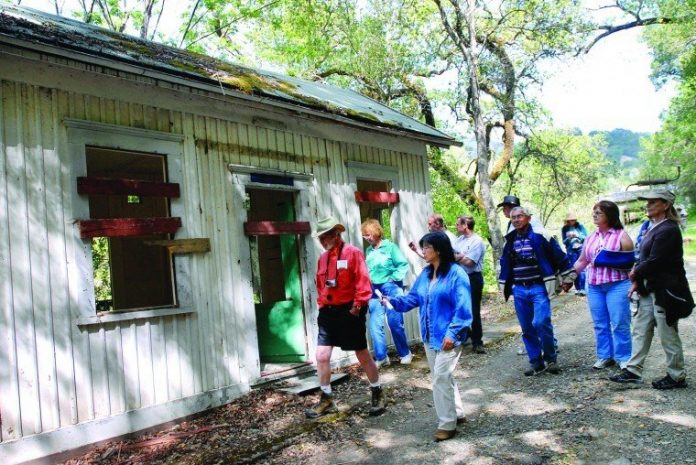

Its landscape is ribboned with meandering paths alongside moss-covered cabins, small forests of ethereal bamboo trees and small, natural pools with water emerging at temperatures between 95 to 115 degrees.

“The hot springs was a place of healing,” said Dominguez-Yon.

Right now, activities such as full moon campouts, soaking in the mineral tubs, volunteering for cleanup work and guided tours are available through appointments and reservations. The hot springs are closed to the general public.

The FOGHS’s goals include making available the hot springs soaking tubs for frequent use, refurbishing some of the original cabins so visitors might be able to stay on site, organizing day-use opportunities for taking walks or having picnics on the premises, making the resort available for private rentals, and revitalizing one or both of the original swimming pools. One of the FOGHS members is even working on building a miniature diorama of the entire resort, which would eventually go on display and give visitors an idea of what the grounds looked like in its heyday.

“We have other people who would really love to see the hotel put into place; maybe not as an active accommodation, but for historic possibilities, such as a museum,” added Dominguez-Yon, of the once stately Gilroy Hot Springs Hotel, which was constructed in Italiante architecture, had 26 rooms and burned down in 1980. “The purpose of this meeting is to get all those hopes/dreams/wishes into the master plan. Now is the time to step forward and say, ‘hey, what about this?'”

The FOGHS is already making headway. Mini-projects such as laying down new pipes began in November 2010, while a full-time, on-site camp host, Craig Thomas, now lives at the Hot Springs; serving as a watchful eye over the historic locale and picnic area.

All this is a microcosm inside Henry Coe’s 87,000 acres of majestic South County backcountry, which was one of 70 state parks threatened with unprecedented mass closure in 2012 due to state budget setbacks. Thanks to the Coe Park Preservation Fund that was founded by a group of private hiking/outdoor enthusiast advocates from the Silicon Valley area, enough money has been raised to give the park an additional three years of life until June 30, 2015.

“Being a public park, we absolutely aspire to have public access. What that entails as far as public insurance and liability, that’s what we have to figure out,” said Dominguez-Yon.

Looking around at the lonesome but breathtaking acreage, it’s easy to envision socialites from the Marriott, Spreckels and Nestle families lounging by the bathhouses and sipping moonshine iced tea, politician’s wives gossiping over earl gray in the 1939 Japanese garden tea house or lively dance parties lasting into the late hours of steamy summer nights.

“During prohibition, it was the place to be,” said Dominguez-Yon during a tour in April. “You could drink there and gamble there.”

In addition to its sparkly legacy dotted by patrons of the rich, famous and well-to-do persuasion, the hot springs are a vessel of cultural significance for local Japanese heritage.

Even after being uprooted and relocated to an internment camp during World War II, H.K. Sakata, who bought the resort in 1938, returned to the springs and invited 60 displaced families to use the escape as a temporary hostel of solace until they could re-assimilate.

With time acting as the resort’s greatest foe, the FOGHS are dealing with aging structures and new regulations that have led to the condemnation of unsafe buildings, overstressed plumbing/electrical systems and increased maintenance expenses. With increased support, they’re hoping to combat the disuse, vandalism, decay and plant overgrowth that has mired the landmark as a place of respite, escape and healing.

From 6:30 to 8:30 p.m. Feb. 2, another meeting will take place to write an interpretive master plan that will make recommendations for the future facilities and plans of Coe. Called the “Henry W. Coe State Park Recreation and Visitor Forum,” the gathering will be held inside the El Toro Room at Morgan Hill Community and Cultural Center. The California Department of Parks and Recreation is seeking a diverse set of recreationalists (bikers, hikers, backpackers, equestrians, user groups, nature enthusiasts, etc.) to share suggestions and comments during the forum, which will be facilitated by the University of California, Davis, and the John Muir Institute for the Environment.

For more details about the meeting, visit www.coepark.org or email sh*******@*****is.edu.

– The California Department of Parks and Recreation will host aGilroy Yamato Hot Springs Public Forum from 6:30 to 8:30 p.m. Jan.12 in the El Toro Room at the Morgan Hill Community and CulturalCenter, 17000 Monterey St. The meeting will include a briefing onthe current use and situation of the springs, along with a publicparticipation process to receive recommendations pertaining to themanagement of the springs.

– Friends of Gilroy Hot Springs is a small group of volunteeradvocates, former residents and state park employees workingtogether to clean up and restore public access to Gilroy HotSprings by creating visitor-friendly spaces and preserving theoriginal structures.

– To become a member, read about member benefits, inquire abouta guided tour or learn more about the history of the springs, visitfriendsofgilroyhotsprings.org or em*******@***********************gs.org for a membership application.Details: Laura Dominguez-Yon at (408) 314-7185.

– To donate: Make checks payable to “Friends of Gilroy HotSprings” or “FOGHS,” addressed to FOGHS, PO Box 1745, Gilroy, CA,95020-1745