Police say omission was unintentional

Gilroy – Police say they don’t know why a brutal sexual assault, reported Oct. 2, wasn’t made public until last Friday. Though police regularly brief the Dispatch on significant crimes, from burglaries to bicycle theft, the incident wasn’t shared with the paper until Nov. 17, more than six weeks after the assault.

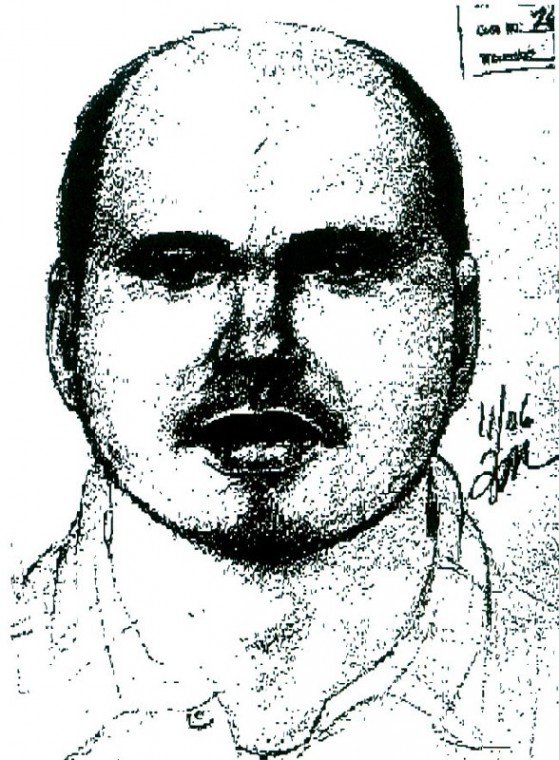

Detective Michael Beebe, who is investigating the case, sent suspect information and an artist’s sketch to the Dispatch for publication Friday. His release described a horrific rape, committed at 1:47am in a central Gilroy alley. The man, a stranger, pinned a woman to the ground and forced himself on her, repeating, “Bitch, you deserve this.”

“This is terrifying, and it needs to be talked about as soon as it happens,” said Dieanna Pemberton, general manager of the Rickenbacker Group. At the downtown business, female employees already walk to their cars in pairs; after learning of the assault, Pemberton said they’re bringing male coworkers with them.

When contacted by the Dispatch, Beebe was unaware that the crime had not appeared on the newspaper’s blotter in early October, when it occurred. The release of suspect information had been delayed, he said, due to scheduling difficulties between the victim and the sketch artist, but publicizing basic information on the incident wouldn’t have hurt his case.

Assistant Chief Lanny Brown said the information “should have been shared,” for public safety reasons.

“I don’t think anybody left it off on purpose,” Brown said. “Everything goes on the blotter, unless the investigating officer specifically comes forward and says, ‘This would compromise my investigation.’ ”

In sexual assault cases, victim information is confidential, but a crime’s time, date and location are public information under California’s Public Records Act, said Terry Francke, legal counsel at Californians Aware: The Center for Public Forum Rights. Sexual assault advocates say public awareness of violent incidents is key to preventing them.

“Personally, I’d want to know,” said Perla Flores, director of Community Solutions’ Solutions to Violence department. “As long as we take client confidentiality and safety into account, we should have as much information as we can get about sexual assaults that are occurring, and where they occur, so people have a heightened sense of awareness … There’s a misconception that sexual assault doesn’t happen here.”

How did a serious assault slip through the cracks? Gilroy police incidents, large and small, are printed out for the briefing room blotter, which oncoming shifts consult when they start work. In some police departments, like Morgan Hill, that blotter is copied, censored for private information like phone numbers and victim names, then given to reporters.

That’s the protocol followed for Gilroy police arrests. But incidents without arrests are handled differently. In Gilroy, an officer simply reads releasable information to reporters off an uncensored blotter, to save staff time.

“Going through all those reports and physically redacting all that stuff would deplete our staff’s time, and create delays for media,” said Brown. “Instead, we read it … It’s human, first-person visual redacting.”

Officer Jesus Contreras, who took the report, printed it for the briefing room blotter Oct. 3, the day after the assault. Whether it made it to the board, however, is unclear. The briefing board is purged monthly, said Sgt. Kurt Svardal, “so we’ll never know whether or not it was in there.” Police still learned about the incident through internal “end watch” e-mails, said Svardal; why the paper didn’t learn of it at all is “a good question.”

“Whenever we have any sort of a sexual assault, it’s a very significant crime,” Svardal said. He was unsure why the incident hadn’t made it to a reporter’s notebook. Some days, officers aren’t available to do so; some days, a reporter can’t stop in to get it. When that happens, said Svardal, an incident might get lost in the shuffle.

“We make sure that we try and put out all the information on the blotter so the paper gets it and has access to it,” he said, “but we’re not going to call a news conference.”

To prevent future omissions, Brown said he’d look into a system of initialing reports, to keep track of which have been shared with the newspaper.

Generally, “the police do a good job of sharing information,” said City Council member Peter Arrellano, “but why it wasn’t done in this case needs to be investigated. Was there a slip up? Someone dropped the ball, and it shouldn’t happen again, especially for a violent crime of this nature.”

Mayor Al Pinheiro agreed. Not all information needs to go public, he said, but if police say the information should have been shared, “they need to get back and find out how that miscommunication occurred – and fix it.”

Thirteen rapes were reported in Gilroy in 2005; 21 were reported in 2004. Nationwide, the majority of sexual assaults are committed not by strangers, but by someone known to the victim. That makes the Oct. 2 assault a very rare case.

But statistics are cold comfort for Pemberton, as she rallies her coworkers to walk together at dusk. On Monday night, she planned to phone her husband when she reached her car, just to check in. News of the rape had rattled her.

“We’re scared,” she said. “Someone should have let us know about this. Just so we can be more aware.”