Evidence collectors help figure out the who, how and when of

crime

Gilroy – The yellow tape is up. Everything inside the barrier is evidence and needs to be evaluated, measured, photographed, collected and reviewed. Risking contamination could mean the case, so a team of specialists are called in to handle the collection process.

Evidence technicians, such as Gilroy Police Department’s Kim Sullivan, arrive on a crime scene and are walked around the site by police who provide a sketch of what they believe happened.

It’s Sullivan’s job to collect evidence to help determine the who, the how and the when. She and the other evidence technicians photograph and videotape the crime scene. She sketches the scene and takes measurements so she can recreate it later in court, if needed.

“If the case ends up going to court I may be asked to testify,” she explained.

Evidence technicians may work two days straight collecting evidence for homicides. They freeze the scene and call in other technicians when fatigue sets in.

She collects fingerprints that will be sent to San Jose Police Department for analysis. Hairs are collected by dusting surfaces with a form of sticky tape. Sullivan mixes a plaster compound to pore into footprint tracks found at the scene.

A special spray can detect any blood at a crime scene by glowing. However, should technicians decide to use it, this spray makes anything it touches unusable as evidence, Sullivan warned. Any blood she finds, she packages in paper to prevent mold from growing,

Evidence technicians will go to the autopsy of a shooting victim to retrieve the bullet for forensic analysis.

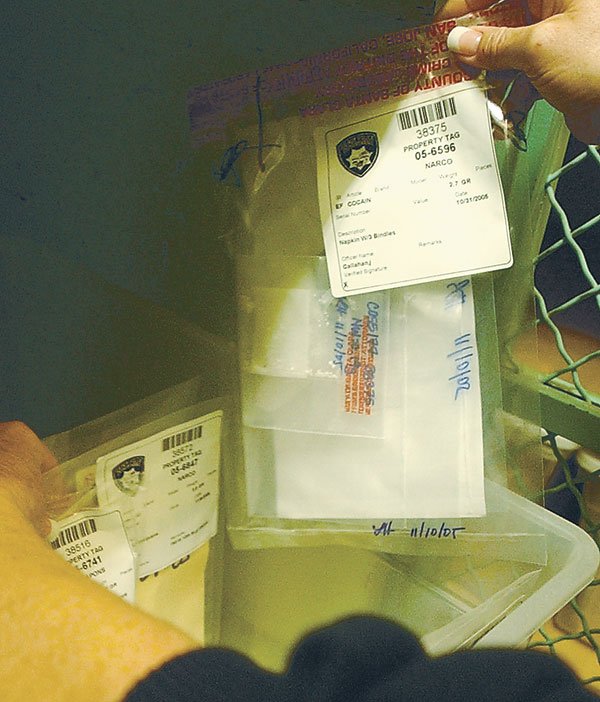

Each piece of evidence Sullivan collects is given its own bar code and logged into the GPD computer system by property officer Nina Sheleman. She is the keymaster and the only person who can unlock the one-way evidence lockers.

Any time evidence is handled or moved Sheleman knows about it. A chain of custody must be compete certifying who touched the material and when.

“You want to show how its changed hands,” she said.

This allows the judge to see that the evidence is not contaminated.

The evidence rooms at the police department are overflowing. Two freezers contain DNA evidence and rape kits. Thousands of photographs sit in labeled envelopes in file cabinets where they will remain for the next 20 years.

Sheleman stands watch over the boxes of baseball bats, crowbars, and sticks collected from fights. Everything is labeled – from red pajama bottoms to bricks.

Over the past three years, Sheleman has purged more than 32,000 pieces of evidence from GPD.

“But we keep homicide evidence forever,” she said. “Ever since the O.J. Simpson case we collect a lot more evidence at homicide scenes.”

Once a week, Sheleman delivers DNA evidence to the Santa Clara County Crime Laboratory.

“We are a full service lab,” said Crime Lab Director Benny Del Re. “Everything that you see on (‘Crime Scene Investigation’) is pretty much what we do. You name it, we do it.”

Scientists at the lab can identify controlled substances using toxicology methods and analyze latent fingerprints, as well as perform DNA analysis. They can lift DNA from everything from blood to sunflower seeds to the bridge of sunglasses.

The crime lab often performs digital enhancements on audio and video recordings. Del Re believes the next wave in evidence analysis is computer forensics.

“We’re just really starting to see the boom,” he said. “A person may have documented a whole crime on their computer, but it may be password protected.”

It’s their job to get it out.

The county lab will sometimes send individuals to help smaller law enforcement agencies, such as Gilroy, analyze blood spatters, which determine whether the victim was sitting or standing when the crime occurred and at what angle.

“We’re not here to determine guilt or innocence,” Del Re said. “We can maybe give closure to families … It’s a bit crazy, forensic science has just taken off with these shows (like CSI) hitting that airways.”

He has worked more than 25 years in the field – before the popular CBS show, before they had national firearm databanks and DNA analysis. He has noticed a phenomena known as the “CSI effect.”

“Juries expect to see some sort of physical evidence that’s associated with the crime now,” Del Re said. “We don’t solve a crime in an hour – it takes weeks, months to get (some testing) done.”

The CSI effect puts pressure on district attorneys to produce where in the past it wasn’t necessary, he said.

The crime lab has hundreds of cases backlogged for DNA testing.

Most of the 59 lab technicians at the county crime lab are not law enforcement officials. However, they understand the significance of evidence.Before evidence is sent back to law enforcement agencies, it must undergo three review findings for quality control.

“I just look at the ramifications of what we’re doing,” Del Re said. “It could mean life or death. It could exonerate somebody. People have been let out of jail from what we do.”