GILROY

– The battle may be over, but the war isn’t.

Days after a government land-use agency rejected a bid to move

the city’s 75-acre sports park unconditionally into city

boundaries, a frustrated Gilroy City Council voted unanimously

Monday to instead begin developing the park as soon as possible

within its current county jurisdiction.

GILROY – The battle may be over, but the war isn’t.

Days after a government land-use agency rejected a bid to move the city’s 75-acre sports park unconditionally into city boundaries, a frustrated Gilroy City Council voted unanimously Monday to instead begin developing the park as soon as possible within its current county jurisdiction.

The council also voted 4-2, with Mayor Tom Springer and Councilman Al Pinheiro dissenting, to abandon the city’s current application before LAFCO to annex the land. Councilman Roland Velasco was absent.

With the votes, the city will move to begin developing the sports park as soon as possible – but may have lost some ability to take future legal action against LAFCO.

But in the end, several frustrated councilmembers decided that months of conflict with LAFCO over local control of the sports park and adjacent land was not worth continuing, especially with conflict over a much bigger fish – the controversial 660 acres east of the Gilroy Premium Outlets the city has targeted for an industrial park – still looming in the future.

That conflict pits city officials – the majority of whom are resentful of potential loss of local control over city plans – against the agency and open space advocates who say they are doing their state-mandated job to protect agriculture and prevent urban sprawl.

“This might not be the battlefield to fight if we want the sports park …” said Councilman Bob Dillon Monday. “But let’s keep an eye on the ball as we move forward.”

Last week, LAFCO rejected the city’s request to unconditionally approve movement of the sports park and at least 35 acres of adjacent private land into city service boundaries.

The city cannot appeal that decision, said City Manager Jay Baksa Monday. The city can still get to work on the fields and utility infrastructure that make up the first phases of the project, but will have to pay property taxes on the acreage – although those funds may be able to be recouped later.

Meanwhile, the adjacent private property owners will likely be forced to reapply in the future to the agency in order to get the boundary change that could lead to extension of utilities and residential or commercial development – a process that could take years.

Although the agency actually approved the annexation of the sports park acreage itself, it said the city would have to develop, submit and follow an implementation plan for a city-wide agricultural mitigation policy outlined in its recently adopted General Plan.

That would have forced the city to replace the sports park property acre-for-acre with other ag land, or else pay the value of the land to an open space agency.

More importantly – and scary, said city officials – was that the agency would then have control and sign-off approval over the policy – which would apply to many future projects, including the 660 acres. To city officials, the agency was overstepping its bounds by acting as enforcer of a city policy.

“LAFCO had no right to do that,” Baksa said Monday. “That is a city of Gilroy function. The real danger is having LAFCO approve what is in essence a local-control decision.”

Meanwhile, forming that policy through a special task force would take 10 to 18 months, officials estimated – meaning more delays on a park where construction could otherwise be underway.

“If (LAFCO officials) don’t like it, (the park) gets held hostage … and who gets held hostage are the kids who will play at the sports complex,” Baksa said.

Both Springer and Pinheiro have said before they’d consider lawsuits against LAFCO if it snubbed the city’s request – something Pinheiro brought up again Monday night. The agriculture mitigation policy is the city’s call – not LAFCO’s, he said.

“I feel at some point in time we need to step up to the plate,” Pinheiro told Council.

But Baksa said City Attorney Linda Callon would have to research the matter.

“As much as we feel wronged, we may not have a legal leg to stand on,” he cautioned.

Springer said leaving the application active would accomplish little, except keeping the door open for a legal challenge to LAFCO. Although he thinks the agency should be challenged, he said individual property owners may have to be the ones to issue it.

“I do think we ought to challenge LAFCO on this,” he said.

But Councilman Craig Gartman didn’t see much benefit in keeping the application active, noting it would suck up valuable city money and staff time fighting LAFCO staff who would likely make the same recommendations as before.

“Sometimes it’s better to retreat and come back to fight another day,” he said. “I don’t see this as an issue (worth) upsetting LAFCO even further. We’re on their bad side now.”

Pinheiro argued that a decision on a potential legal challenge would come if the city submitted an ag mitigation policy in good faith, but had it rejected by LAFCO. But he was unsuccessful in swaying his colleagues.

“There’s a time and place where you just stand for what’s right,” he argued. “We’ve done it the right way and played by the rules.”

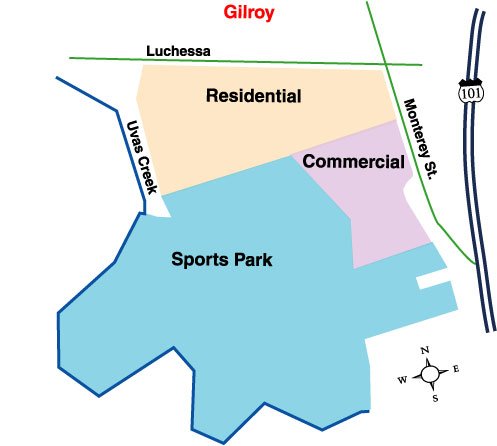

City officials had argued without including the connecting residential and commercial land, LAFCO would be violating its own policies by forming a “land island” of city land, while losing some ability to master-plan the whole area and ease in widening Luchessa Avenue for future west-side residential development.

And they were upset that the agency asked them to abide by the ag mitigation policy at all, noting that the request came late in a months-long process and after an environmental report on the sports park had already been approved.

With the decision by LAFCO and the Council, the adjacent private landowners lose the ability to develop their land for residential or commercial purposes – and, they say, farm it effectively. Several landowners told LAFCO the benefits of annexation would outweigh the loss of the tracts of farmland, which they said would be too small to farm efficiently with the massive sports park acreage removed from production. But open space advocates have said the agency is just doing its job to protect agriculture.

They’ve told the commission that it is important to see the ag mitigation policy developed before approving the park annexation to ensure the city keeps its word and develops one in a timely fashion.

Meanwhile, enough undeveloped land already exists within city borders to necessitate moving the private commercial and residential land in too, they said.

“There’s local control, it’s just that LAFCO is asking the city to make choices about what land it wants included in (boundaries),” said former Councilwoman Connie Rogers, a member of the group Save Open Space.And they said holding the city to its own ag mitigation policy is a reasonable standard. LAFCO staff suggested the move because former mitigation for the sports park – acreage in an ag preserve to the east of the city – would be damaged by the city’s move to redesignate the 660 acres for an industrial campus.

That campus itself still looms like a storm cloud over relations between the city and LAFCO. LAFCO put the city on notice that it will most likely deny any large annexation requests if the city adopted the General Plan with plans to bring the 660 acres of agricultural land east of Gilroy Premium Outlets into the city’s 20-year growth boundary.

Formed in 1963 to combat urban sprawl in California, LAFCO is an independent agency with the power to reject any municipal or private annexation request.

LAFCO staff have previously stated that no annexations will be approved unless the agency endorses the city’s 20-year boundary, an endorsement the city argues it never consented to. The disagreement lies in differing interpretations of an agricultural compact the city, county and LAFCO entered into in 1996.

LAFCO claims the compact, along with the agency’s own policies, states that the city must maintain its eastern growth limit to preserve agricultural land. If the 660 were brought into the city’s 20-year planning boundary and LAFCO refused to adopt the new boundary, any future annexation requests would be dead on arrival.

However, Gilroy officials say LAFCO’s policies conflict with the compact, which specifically states that Gilroy can change its growth boundaries through a General Plan update process.

City officials complained that LAFCO’s early involvement – before the General Plan was completed – was an unprecedented, premature step. But open space advocates countered that the agency’s move was a logical, courteous step meant to let local leaders know the full ramifications of their actions while they could still make changes.