GILROY

– As the city tries to hammer out a conservation policy for

agriculture, farmland owners and open space activists are digging

in for an all-out battle of political, and potentially legal,

will.

A special city task force has until March to rewrite a farmland

preservation bill that already has been rejected by City Council

once. And the effort is proving more and more difficult as the

question regarding how much developers should pay when they

urbanize the South Valley’s dwindling agricultural land becomes

muddier.

GILROY – As the city tries to hammer out a conservation policy for agriculture, farmland owners and open space activists are digging in for an all-out battle of political, and potentially legal, will.

A special city task force has until March to rewrite a farmland preservation bill that already has been rejected by City Council once. And the effort is proving more and more difficult as the question regarding how much developers should pay when they urbanize the South Valley’s dwindling agricultural land becomes muddier.

Farmland owner Richard Barberi, who was named chairman of the task force Wednesday, and Lee Wieder, who represents a group of farmland owners controlling 660-plus acres, say if the ag preservation policies called for in Gilroy’s General Plan get implemented as is, the matter will likely be settled in court.

“I know of no other city or county that has requirements this harsh,” Wieder said. “It seems the real agenda here is to stop growth and preserve open space. It’s not about preserving agriculture.”

Meanwhile, city staff is holding firm in its convictions that the task force must develop a plan that follows the General Plan. Otherwise, the city faces $100,000 in environmental work to rewrite a portion of the planning document.

If it rewrites the General Plan, the city could find itself in a lawsuit with local open space activists who already hired a lawyer to poke critical holes in the task force’s original farmland preservation bill.

“At this point, I think it would behoove the city to bid the environmental work and see how much it will cost them to reopen the General Plan,” Wieder said.

Essentially, farmland owners want flexibility in the city’s conservation policies. Under the General Plan, developers must preserve an acre of farmland when they develop an acre of farmland elsewhere.Farmland owners are not against mitigation such as this, but they say developers should have the ability to purchase so-called development rights, rather than the actual land itself. When development rights are purchased, land can still be cultivated by farmers, but it can never be used for housing, industrial or commercial units.

Paying for development rights makes developers happy because this type of mitigation is cheaper than paying market value.

And it makes ag preservation activists happy because it saves at least some farmland when farmland elsewhere gets developed.

Gilroy’s General Plan allows development rights to be purchased, but with a caveat: developers must pay the regular market price for the land.

“It’s tough ag mitigation, no doubt about it,” Gilroy Planning Division Manager Bill Faus says. “But it’s what City Council approved in order to bring in the 660.”

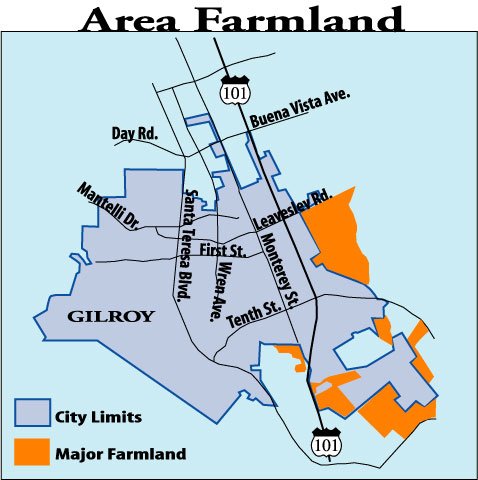

The 660 refers to those farmland acres east of Gilroy’s existing boundaries which owners want to eventually sell to developers for campus-style industrial parks. It was zoned as county land before the most recent General Plan was approved.

Wieder says the caveat is so extreme that no one on the task force – and perhaps no one who supported the incorporation of the 660 – fully understood its implications.

In a letter Wieder wrote to City Council, he claims staff and the task force understood there would be three mitigation options for developers:

• Purchase an equal amount of farmland

• Purchase development rights on an equal amount of farmland

• Pay a fee that would cover the cost of development rights on an equal amount of farmland.

In response, Faus Wednesday issued copies of the General Plan’s text to Council and the task force.

The General Plan text is clear. Three payment options are spelled out, but each of them must equal the cost of buying the land outright.

For open space activists, the General Plan’s guidelines are tough but fair. They allow development of ag lands but at a price.

For farmland owners like Barberi, the guidelines are a virtual anti-growth wall around Gilroy. He says it’s so inherently unfair, he is ready to go to court if the task force and City Council cannot come up with something more agreeable.

Barberi owns $3 million worth of land off Luchessa Avenue, close to where the city sports park is planned. Barberi says he, and the two other parties he owns the land with, can only charge farmers $350 per acre to cultivate his land. However, property tax on the 23-acre parcel runs more than $36,000 a year.

“So how is that fair?” Barberi said. “How do you get someone to buy land in Gilroy to develop it when they have to pay double the amount there.

“This won’t hurt the farmer, this won’t hurt the contractors, they’ll just go somewhere else,” Barberi said. “But this will hurt the families of Gilroy who thought their land would be worth something some day.”

The task force is scheduled to meet two more times before it presents a new proposal to City Council, likely March 15.

On that date, the task force will face a business-friendly Council that is minus former Mayor Tom Springer, the most vocal critic of the group’s preservation proposal.

For now, Council members are backpedaling on the issue as they wait for the task force to finish its work.

Mayor Al Pinheiro would not say whether he would support reopening the General Plan process.

“The task force needs to come up with a plan first; that’s the appropriate way of doing this,” Pinheiro said. “We need to preserve ag land for the future, but am I ready to make developers today pay unfairly for what wasn’t done in the past? No.”