The first thing you notice when you are in the eye-in-the-sky at one of Gilroy’s busiest department stores are the shoes people are wearing when they walk in.

If they are worn out or dirty, there is a good chance the customer is going straight to the shoe department to put on a new pair and leave without paying.

The second thing they notice are the purses, the big flat ones, like those sold by Michael Kors, which can hold a lot of items without flaring out, or the backpack style, which are empty on the way in and full on the way out. They call those “stat bags,” as in the person carrying it is probably going to steal something and the store detectives — who now are called LPOs or Loss Prevention Officers– will get another statistic to add to their records.

A big local store let the Dispatch see a day in the life of its theft prevention department, on the condition that we don’t name the store or employees. What we got was a starkly honest view of the shoplifting world that was as depressing as it is amazing. We were surprised by the lengths people will go to steal items as unlikely as T-shirts and underwear, and by the ages of the thieves, which this year ranged from 12 to 92.

Shoplifting and retail theft are on the rise, locally and nationally. At this store 125 people were caught in the first 10 months of the year, with $34,000 of stolen goods. It is well on the way to beating last year’s record of 135 thieves caught. Thefts peak during the holidays when shopping also peaks.

In Gilroy there were 954 thefts of all kinds this year and 184 burglaries, thefts that involved breaking into a store or home. Both were down 11 percent from last year. There were also 39 robberies, where a weapon or threat forced someone to give money or goods up 8 percent.

The Outlets were hit particularly hard this year, Gilroy police said, with the Fossil store losing $500,000 in one summer theft. Some 83 percent of stores across the country reported a rise in theft, according to a study by the National Retail Federation, a trade association. That organization has also studied a new, ganglike problem called Organized Retail Theft, in which groups target businesses and travel the state or country stealing from them in groups.

The average loss from organized theft was $700,259 per $1 billion in sales over the past year, a significant increase from $453,940 last year.

“The biggest part of this job is patience,” says an officer we’ll call Amanda. “If I starve to death or get a bladder infection, it’s because every time I’m about to take a break I see someone shoplifting.” The result is hours of monitoring the suspect and waiting for action. A lot of shoplifters think that if they stay a long time in the store, the detectives will grow bored and ignore them. That’s not an option for the employees who make $10-$24 an hour to prevent loss. They’ve watched women take five or six hours before they try and walk out with stolen goods.

Her strangest case was having to arrest a high school classmate, who walked out with $2,400 of jewelry. The woman had spent more than two hours in a dressing room, carefully cutting off labels and stuffing handfuls of jewelry into a pocket she cut into the lining of her purse. She stuffed receipts and labels in a wallet and inside a dress she had cut open with a razor blade.

“It was the first time I could stop someone by name,” she says. “My adrenaline was pumping.” The woman–in an all too familiar pattern–first claimed the detectives had set her up. Then, later, she pleaded guilty. Most thieves deny they took anything or claim it was a mistake, until the officers show them the tapes or describe what they saw.

What thieves don’t realize is that their actions in a store, even in the places they think don’t have cameras, are monitored. Undercover officers also check each dressing room before and after a client walks in, although there aren’t cameras in there.

Thieves shoplift as differently as men and women shop. Shoplifting women take hours to prepare and hide their goods, cutting tags, using magnets or tag removers bought on the Internet to disable theft protection devices, such as ink tags that mark stolen goods. Some line their purses with foil, in an attempt to fool the automatic theft detectors at the doors.

“Men will pop off their shoes or take a belt, take a jacket or some sweats,” says Amanda. “But girls, they take their time. They’re in here for hours and they load up bags and they layer clothes.”

Men can be in and out in two minutes. Women are largely “fitting room cases,” doing their work in the dressing rooms. Men often try to conceal goods on the store floor or snatching and grabbing goods and running out a door.

“I look at the way they carry themselves,” says her partner, Alex. “A real shopper will look at the prices, look at the sizes, check them out from top to bottom. The stats–or shoplifters–don’t look around before they pick something. They’ll be in the area and look up for the cameras. Then, they pick up, not looking at the size or prices.”

We watch a tape of one man who spent 25 minutes in the underwear department before he stuffs a pick package of white undershirts into his baggy pants. Another who has taken a backpack off a shelf and stuffed it with stolen goods wanders the outside aisles of the store, as if he thinks the cameras wouldn’t be focused there. The detectives watch every move and nab him as he passes through the metal detectors past the checkout stands.

“People don’t realize how often it happens,” says Amanda, which is one of the reasons she wants to publicize the damage being done to stores. “When I came into this job, I had no idea. Even associates. We see them steal. I had no idea that so many people who worked here would be shoplifting.”

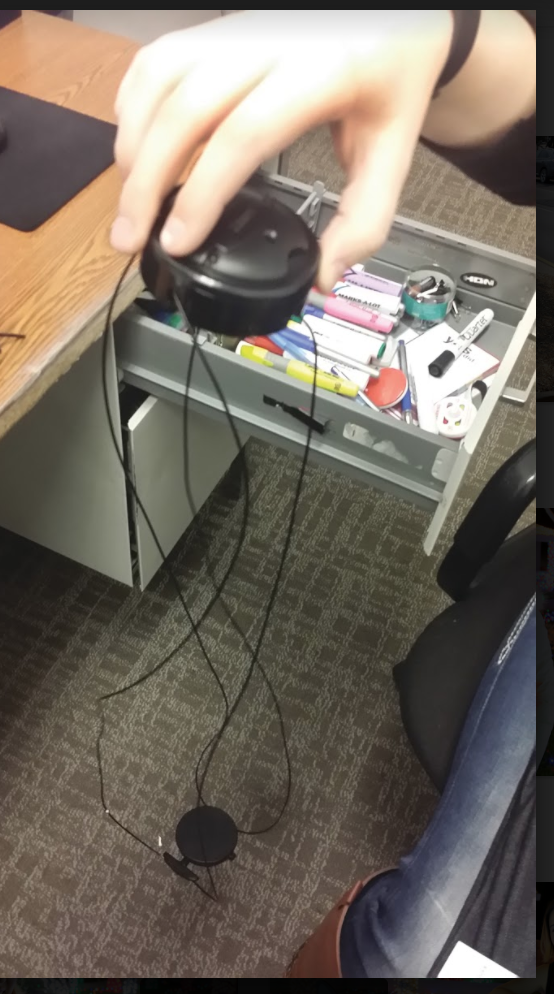

The most popular items are Levis, Nike shoes, robot vacuum cleaners, dress shoes, jewelry, beauty supplies and electronics, the officers say. After a big theft, loss officers can take hours linking stolen goods to the labels they have stripped off and hidden.

Thieves who take more than $20 can be prosecuted, with many getting a citation there and released. In court, they have to pay a fine and make restitution for the cost of the goods, even if they have returned them.

With the tapes, it’s rare for the officers to have to go to court. Most thieves plead guilty. Thefts over $950 are felonies and handled by police and the district attorney. All of the officers interviewed were disappointed with Proposition 47, which decriminalized property theft and reduced prison sentences.

The officers have to be vigilant, because there is no profile of a shoplifter. They caught three girls, 12, 13 and 14 with backpacks each holding $900 of perfume, candy, earrings, shirts and electronics. Then, they caught a 92-year-old woman with a $65 dress she stuffed into her bag. They caught another older woman who stole an iPhone from the cart of another shopper. They’ve caught teachers and government workers who begged them not to publicize the cases. They even caught a woman who works with at-risk kids who filled a cart with baby clothes, grownup clothes and jewelry.

“I always ask ‘What are you doing in here stealing?’,” says Amanda. “She goes, well, my husband left me and I’m going through a divorce and don’t have any money. Like, I feel for people, I really do, I feel really bad for them. I could understand if she was stealing clothes for her baby because she needs them. But what are you stealing these clothes for yourself and this jewelry for? You know, I don’t feel bad for you when you are doing that.”