Guillermo Jimenez Sr. carefully spelled his name

– the only word he can write – as urged by the dental

receptionist, he said. He felt grateful. Lacking insurance, the

58-year-old landscaper had little means to pay for his two visits

to City Dental on Monterey Street.

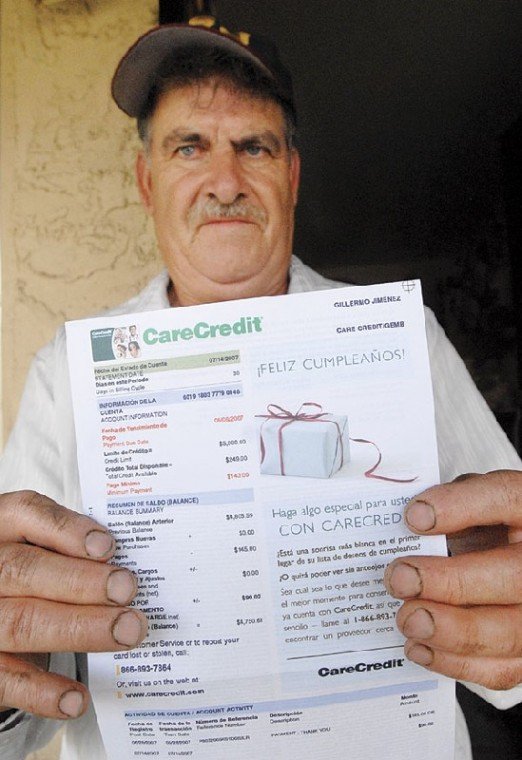

Gilroy – Guillermo Jimenez Sr. carefully spelled his name – the only word he can write – as urged by the dental receptionist, he said. He felt grateful. Lacking insurance, the 58-year-old landscaper had little means to pay for his two visits to City Dental on Monterey Street. The receptionist filled out the forms, he said, and he signed them.

One year later, Jimenez is paying nearly as much in fees as for his dental bill, after making a late payment to CareCredit, a General Electric company that offers monthly payment plans for healthcare. Jimenez signed up for CareCredit, he said, but didn’t understand what it was.

His dentist said he should have.

“Everything was explained to him,” said Dr. David Nader of City Dental. “I don’t know what to say … We’ve never had this problem. Everyone loves CareCredit.”

CareCredit works like a credit card: Dentists, chiropractors and cosmetologists charge the full price of a procedure to a patient’s account. The patient pays off the sum in monthly installments. But like a credit card, the bills can mount. CareCredit offers zero-interest plans, but if a patient exceeds their credit limit, pays late or fails to pay in full, interest rates skyrocket to 23 percent or higher.

That’s what happened to Jimenez, who now pays $92 in finance charges a month, on top of his $148 minimum monthly payments. His original balance exceeded $5,000, and he’s chipping away at it – slowly. The Gilroy man said he earns roughly $1,630 a month at Western Tree Nursery, packing seedlings. The bills have posed a hardship for his family.

“We can’t go out to eat like we used to,” said his wife, Maria Quintania Jimenez, speaking in Spanish.

Countywide, health coverage has grown more expensive and less widespread, with job-based health care costs nearly doubling between 2000 and 2006, according to a report by Working Partnerships, a San Jose nonprofit that aims to narrow the gap between the rich and poor. As costs grow, payment plans like CareCredit have been marketed more aggressively to consumers, said Mark Rukavina, director of the Access Project, a Brandeis University research effort. Zero-interest plans look like “sweet deals,” Rukavina warned, “but one late payment, and the rate can jump to 25 percent … Not so sweet.” Some patients may opt to pay full price, over time, for procedures that could have fallen under a charity care policy, he said.

“These verge on predatory,” Rukavina concluded.

Healthcare credit cards haven’t hit the mainstream yet: The cards are only available to the creditworthy, and they’re typically used for elective procedures, not routine healthcare, said William Parrish, CEO of the Santa Clara County Medical Association. That pattern holds true in Gilroy, where CareCredit is accepted by 16 dentists, three chiropractors, a medical spa and a veterinarian. Limited dental plans such as the state-run Denti-Cal, which Nader says doesn’t cover crowns, bridges or tooth implants, have upped the appeal of CareCredit and similar financing options for dentistry.

But for exceptions like Jimenez, the risks are worrisome, said Theresa Garcia, vice-president of California policy for the nonprofit Children Now, who noted that half of bankruptcies are due to medical issues. Credit cards are an unlikely fix, she said.

“It’s a very short-term solution,” said Garcia, “for a very long-term problem.”