As the world marks the centennial of the sinking of the RMS Titanic, my own thoughts recall an ordinary object – a toothbrush salvaged from the debris field surrounding the rusting hull of the great oceanliner that found its final resting place two miles below the Atlantic’s surface.

In 1994, I saw that toothbrush behind glass in a display case at a special Titanic exhibit at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England. It helped me feel a profound connection to the catastrophe when, 100 years ago, more than 1,500 people perished in the ocean’s ice cold waters. I pondered that perhaps one of the passengers had used the toothbrush to clean his or her teeth that April night, never realizing that the Titanic was on a collision course with human tragedy.

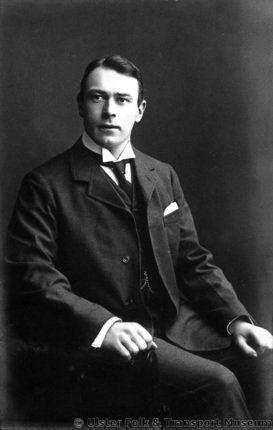

We can never know for certain who exactly might have owned that toothbrush, but I’d like to imagine it belonged to the Titanic’s first-class passenger in cabin A-36. That gentleman was Thomas Andrews.

In the 1997 James Cameron epic film “Titanic,” Andrews plays a minor role. But more than any other passenger on board that fateful voyage, he knew too well the peril the ship faced from damage done by the iceberg grazing its hull. The Titanic was Andrews’s creation. He had served as the head engineer in designing the largest ocean vessel of its age, a ship some mistakenly called “unsinkable.”

Since his days as a young Irish lad in Belfast, Andrews loved ships and worked his way up the ranks from an apprentice in the ship-building firm of Harland and Wolff. In 1907 when he was in his early 30s, the company picked him to oversee the plans for two White Star superliners – the RMS Olympic and its sister ship, the Titanic.

Unfortunately, company managers overruled Andrews in the two key safety components for the ships he had requested. They said no to his request to double the number of lifeboats to 64. And they said no to Andrews in his request to build a double hull that would extend up to the B deck. Their cost-cutting decision would result in many deaths five years later.

At 11:40 p.m. on April 14, 1912 when the Titanic’s starboard side struck the iceberg, Andrews was in his stateroom looking over blueprints of the ship and planning improvements.

Soon after, Captain Edward J. Smith summoned Andrews to inspect the damage. The engineer discovered that sea water was flooding the first five watertight compartments. If more than four compartments filled, he knew the ship would sink. He estimated they had an hour. He also reminded the captain that the Titanic did not have nearly enough lifeboats for all onboard.

Andrews helped with the emergency evacuation, waking up passengers in their staterooms and telling them to put on their lifebelts and go up on the deck. Realizing the full extent of the horror they all faced, he forced reluctant passengers and crew members into lifeboats. Knowing there were not enough boats, he threw deck chairs over the railing into the Atlantic Ocean in the hope that some might be able to use them for floatation.

As the ship listed, Andrews was last seen by a steward in the first-class smoking room. The steward later said the engineer was staring at a painting titled “Plymouth Harbor” that hung over the fireplace. No doubt, the heroic designer of the ship considered his own fate and the fate of many people onboard that night. He knew he would never return to Ireland to see his wife and baby daughter. His body was never found.

A telegram reached Andrews father four days later. It read: “Interview Titanic’s officers. All unanimous that Andrews heroic unto death, thinking only safety others.”

The drama of the Titanic’s sinking impacts us today. The story is one of desperate human survival, the kind of narrative that strikes us all at the most primal part of our psychology.

I’d like to suggest that the tragic tale of the vessel Andrews built can provide us with a lesson in 2012. It’s an important lesson warning against the idolatry of technology. Human beings can be ingenious with the machines they design. But if our ingenuity is not tempered with humility, inevitably human tragedy will result.

We’re seeing that tragedy unfold now around the world with the climate changes caused by the global warming produced by civilization’s technological infrastructure so highly dependent on fossil fuels. Andrews would warn us to steer clear of the icebergs of our own folly.