Different techniques, including some that do not require

surgery, can bring welcome relief to sufferers

By the Faculty of Harvard Medical School

Q: Can I get rid of varicose veins without surgery?

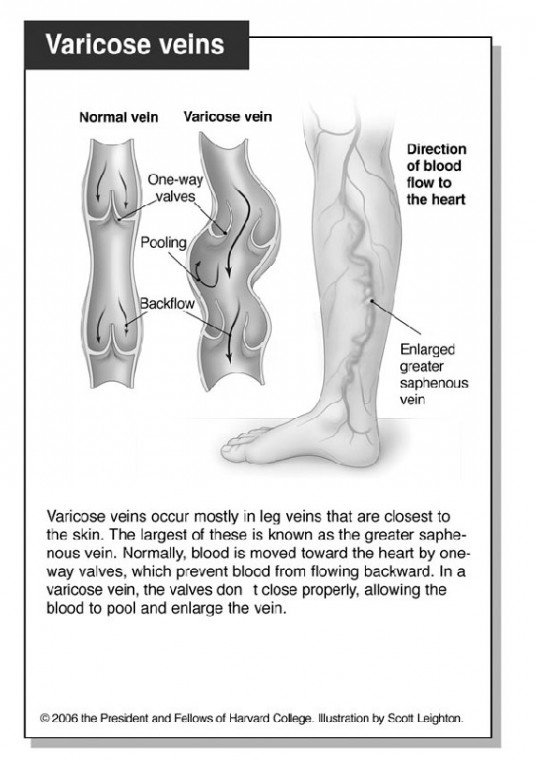

A: Most people think that varicose veins – large, dark-blue or purple veins that bulge above the skin’s surface – are mainly a cosmetic problem. But they can also cause discomfort and lead to other medical problems. Several nonsurgical treatments, using lasers or radiofrequency energy, can remove varicose veins and prevent those possible complications.

Varicose veins occur mainly in the legs because those veins must propel blood a long distance against gravity – from the legs back up to the heart (see graphic). The related spider veins are smaller and look like red or blue spider webs. They also lie close to the skin’s surface but don’t bulge or cause discomfort.

Varicose veins can cause symptoms such as a dull ache, heaviness, burning, pressure or weakness in your legs, particularly after you’ve been standing or sitting for a long time. You can usually relieve this discomfort by elevating your legs. At night you may develop a painful muscle spasm in your calf (a charley horse). Your feet and ankles may swell. And the skin around the varicose veins may itch, become dry or develop a rash or a brownish or bluish discoloration.

You may want to remove or fade varicose veins just because of their appearance. But more aggressive treatment is considered medically necessary only when self-care doesn’t relieve symptoms enough for you to carry on normal activities. Varicose veins should also be treated if they have ruptured or caused difficult-to-treat sores or thrombophlebitis (swelling due to a blood clot).

Spider veins and very small varicose veins can be treated with injection therapy (also called sclerotherapy). The physician injects small amounts of an irritating chemical into the vein. That causes the lining of the vein walls to swell and stick together, permanently sealing the vein. Afterward, you must wear compression stockings for a week or two to keep the vessel closed and to prevent bruising and tenderness. Possible complications are allergic reactions to the irritant chemical, stinging or burning at the site of injection, swelling and skin injury. Once blood is no longer flowing through the vein, scar tissue develops and the vein gradually fades. Brown lines may develop in the treated area, but these usually fade.

Doctors can also treat spider veins by passing a laser over the surface of the skin. Bursts of laser light shrink the veins, while ice and a topical anesthetic help protect the skin and reduce pain. Laser therapy usually requires two to three treatments in a physician’s office and is suitable only for very fine veins. There may be some temporary redness or swelling after the procedure. Like sclerotherapy, laser treatment doesn’t prevent new spider veins from appearing near the treated ones.

For varicose veins, the laser energy is delivered to the inside of the vein by a procedure called endovenous laser therapy (EVLT). Guided by ultrasound, the physician punctures the vein and inserts a guide wire to the point where blood begins flowing backward. Then a laser fiber is inserted, and the laser is fired to heat the vein from the inside. The resulting inflammation makes the walls of the vein stick together, eventually forming scar tissue. It takes about three minutes to treat nearly 16 inches of vein this way under local anesthesia in a physician’s office.

You can quickly return to normal activities, though you must wear compression stockings for several days. Symptoms may improve in a week or two because of reduced pressure in the vein. But changes in appearance may take several months. About 5 percent of people who get this procedure develop numb areas near the knees or ankles, but feeling almost always returns within a year. In about 7 percent of cases, the varicose veins reopen within two years. If you are considering EVLT, look for a physician who has experience in performing such procedures under ultrasound guidance.

A related technique uses radiofrequency waves instead of lasers to heat the interior of varicose veins. Called the Endoluminal radiofrequency thermal heating (VNUS closure procedure), it can also be performed in a physician’s office under local anesthesia. But it takes longer (about 20 minutes) and may cause swelling and pain. The recurrence rate is about 10 percent.

The physician in your community who’s most knowledgeable about these procedures may be a dermatologist, interventional radiologist, plastic surgeon, or vascular surgeon. Vein treatment centers may also be available in your area.