The cacophony of young voices reverberating through the halls of

Sixth Street Prep School sounded like the students had put down

their pencils and mutinied, a visiting teacher from Gilroy

said.

The cacophony of young voices reverberating through the halls of Sixth Street Prep School sounded like the students had put down their pencils and mutinied, a visiting teacher from Gilroy said.

But a peek into Nicole Gore’s second grade classroom revealed a very different picture. Not an eye strayed from Gore as she strolled around the classroom, using an electronic pad to jot notes that were projected onto the board. At her cue, the children entered their answers to math questions using remote control responders.

“I really hope we got 100 percent,” Gore said to her students. “I really want to celebrate.”

The students held their breath as she clicked to view their answers: not a single one wrong.

“Oh yea, baby,” they sang.

With 90 percent of its students below the poverty line and half its population speaking little or no English, Sixth Street Prep faces many of the same challenges as Gilroy schools. But instead of making excuses, the charter school did the last thing most schools do in its situation: teachers turned their backs on textbooks and worksheets, homework and busywork, and watched as their students’ scores skyrocketed.

The school added 300 points in eight years to its score on the 1,000-point Academic Performance Index, blowing by the state’s target score of 800 back in 2006, without batting an eye. With a current score of 938, they’re one of the top schools in the state.

“Give me a challenge and I’m up for the task,” said Principal Linda Mikels, the driving force behind the school’s success. “You give us a big task and that just energizes us.”

Even though Sixth Street is a charter school, their success “absolutely” transfers to other, larger schools, Mikels said. And Gilroy Unified School District is catching on. Last week, more than two dozen teachers from Eliot and Las Animas elementary schools gave up two days of their February vacation and made the seven-hour trek to Victorville in southern California to spend a day observing classes.

After hours of riding in a cramped, dusty school district minivan with Eliot Principal James Dent at the wheel, his teachers piled out, stretching their legs and taking in the vast, desolate terrain. A spider web of power lines crises-crossed overhead and spindly Joshua trees speckled the horizon. A town of about 100,000 people, Victorville sits at the edge of the Mojave Desert.

Walking up the front steps of Sixth Street Prep is like taking a step back in time. Built in 1922, the school once served as the town hall. The wooden floors and high ceilings now house about half of the school’s 230 students. The younger grades of the school – which teaches kindergarten through sixth grade students – are taught in classrooms across the street. At 8 a.m., Mikels threw open the front doors and the children streamed in. Her crisp black suit accentuated with a bright scarf, Mikels greeted each student by name.

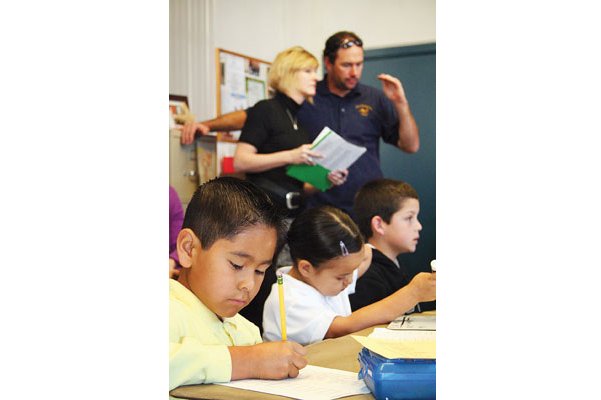

Every week, dozens of teachers come from across the state to visit Sixth Street Prep. Except for a few disinterested glances, most students ignored the adults who circled around their classrooms looking at children’s work and taking notes.

Inside the classrooms, the worksheets and textbooks that clutter most schools are conspicuously absent. Instead, students work through problems on well-used white boards.

Each problem took several minutes as students read the question out load and visualized the situation. While mumbling key rules and reminders, they scribbled their answers on the white board, then entered them using clickers. After every problem, the class reviewed their reasoning and answers with their teacher, discussing why they chose the answer they did or rejected the choices that were incorrect.

“I knew that just marching through the textbook was not going to get my students to proficiency,” Mikels said.

Sixth Street teachers also abide by a no-homework policy. About four years ago, the schools did away with homework and extended the school day by 45 minutes.

“We had accepted 100 percent responsibility for student achievement and yet we were doing what other schools were doing in a brainless kind of way just because it’s always been done and assigning homework,” Mikels said. “As we confronted the brutal facts, we recognized that what we were doing did not align with what we were saying.”

Sixth Street Prep made a pact with its parents:

“You will provide a loving home, meet your children’s needs physically, spiritually, feed them well, love them well, encourage them every day,” Mikels said. “We will take care of the academics.”

By doing away with homework, Sixth Street Prep eliminated the excuse that some children don’t succeed because of parents or poverty or previous years’ failures, Mikels said.

“It was an equity issue,” she said.

The year the school eliminated homework was the year it eliminated the glaring difference on standardized test scores between students from different economic backgrounds or ethnicity – commonly known as the achievement gap.

The methods being used at Sixth Street are “the complete package,” Dent said, which is why he has already created eight model classrooms at Eliot and encourages all his teachers to visit the school.

“You instantly see the difference in the students,” Dent said. “You hear how they talk to each other, how they communicate, how they express their ideas and they’re just functioning at such a high level. And then you go and you actually see what the teacher’s doing and what the kids are doing daily and you realize why they got to that point.”

The combination of teacher collaboration, technology and instruction rooted in California’s academic standards left many Gilroy teachers eager to return to their own classrooms armed with the tools necessary to effect the changes they had witnessed at Sixth Street.

“After leaving Victorville, I was excited,” said Marwa Yousofzoy, a third-grade teacher at Eliot who has already begun implementing some of Sixth Street’s practices in her own classroom. “I was re-energized. It was an amazing trip.

“The kids love it,” she continued. “The kids just eat it up. They are so excited to be in the classroom. They’re happy, so it’s exciting for me.”