By the Harvard Medical Adviser

Q: I recently read an article about the growing trend of male

hormone replacement therapy, where older men are prescribed

testosterone. I know testosterone used to be given only to men with

very low levels due to disease. What’s changed, and is this

treatment right for me?

By the Harvard Medical Adviser

Q: I recently read an article about the growing trend of male hormone replacement therapy, where older men are prescribed testosterone. I know testosterone used to be given only to men with very low levels due to disease. What’s changed, and is this treatment right for me?

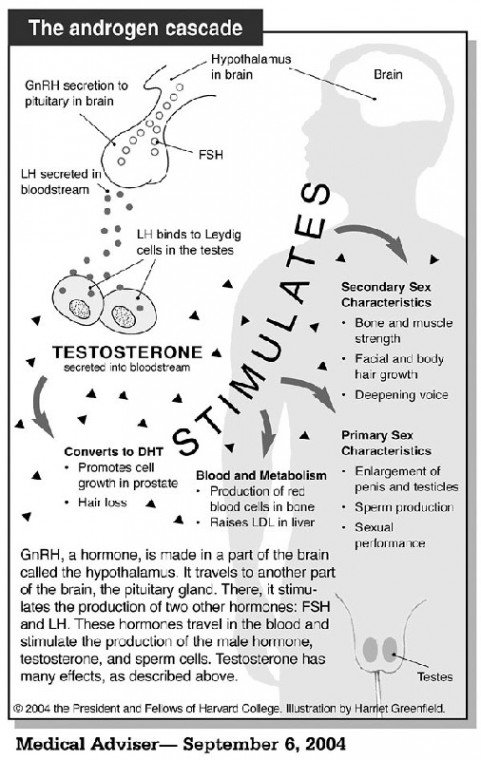

A: Doctors have recently started recommending testosterone replacement therapy for their aging male patients. The purpose is to reverse the gradual decline of the hormone as men age and go through andropause (the male version of menopause). Men’s testosterone levels peak at age 17 and plateau until they start to slide in the 30s and 40s. By age 80, the level will be about half what it was at its peak. Raising low testosterone levels has potential benefits, but also poses risks that have to be considered.

In adult men, testosterone plays a role in maintaining muscle mass and strength, fat distribution, bone strength, and red blood cell production, as well as libido and sperm production. In younger men, testosterone levels fluctuate quite a bit, usually spiking in the early morning. But in older men, the peaks and valleys flatten out, so getting an accurate measurement isn’t difficult.

Prescription testosterone is given as a gel that is spread on the upper arms, shoulders and abdomen after a morning shower and absorbs through the skin. Testosterone used to be given via patches, but these have since given way to the spreadable gels. Injections are also available.

Mainstream medicine has been cautious about the widespread use of testosterone. One big worry is that higher levels of testosterone in the blood might increase the risk of prostate cancer, but thus far there is little evidence to support this fear. In fact, there’s reason to believe that in men with naturally high levels, the hormone may act as a prostate cancer inhibitor. On the other hand, it is clear that existing cancerous prostate cells need testosterone and related hormones to grow. About half of all men over age 50 harbor cancer cells in their prostate that aren’t causing symptoms or doing any real harm. Theoretically at least, testosterone treatment might “wake up” those cells and make them aggressively cancerous. To guard against that, some doctors insist on a prostate testing, including a biopsy, to rule out the presence of cancer before they start a man on testosterone therapy.

Many of the other perceived risks of testosterone treatment appear to be unfounded. Testosterone does not raise blood cholesterol, increase the risk of diabetes, or promote atherosclerosis in the arteries of the heart. In fact, treatment with testosterone has been shown to widen coronary arteries and may even help angina. Red blood cell counts sometimes go up, although this is more common with injections of the hormone than with the skin gel. For men with anemia, that side effect could be a plus. Still, doctors who prescribe testosterone must be careful about monitoring red blood cell counts, since higher red blood cell counts can also make the blood thicker and therefore more likely to clot.

So, who qualifies as having low testosterone and who needs treatment? The answer to this is not well-defined. The clinical trials so far have been too small or too short, or both, to draw firm conclusions and experts disagree. For example, Dr. Peter Snyder of the University of Pennsylvania suggests the following in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM): For men over 65, only those with very low testosterone levels (below 200 ng/dL) should be treated; testosterone levels should be monitored to tell whether the treatment is working; and doctors should watch for testosterone-dependent diseases, such as benign prostate enlargement, prostate cancer, worsening of sleep apnea, breast tenderness and elevated red blood cell counts.

Dr. Abraham Morgentaler, a Harvard-affiliated urologist and one of the co-authors of the NEJM review article, regards Snyder’s advice as highly conservative. For example, he says 400 ng/dL, not 200, is the cutoff used for low testosterone by many urologists. In his opinion, doctors should let the symptoms be the primary guide, with testosterone levels serving as useful backup information.

But there are ways to slow the aging process that are certifiably safe and “natural,” if not quite as easy as smearing on a hormone-laden cream every morning. Weight-bearing exercise builds muscle mass, keeps off fat and makes bones stronger. Walking keeps the cardiovascular system in shape. Fatigue often can be traced back to solvable sleep problems. Finally, we tend to want to defy age, when just a little more acceptance would make us relax about it. Eighty doesn’t feel like 18 or even 38, but should men want it to?

If you would like to e-mail questions to the Harvard Medical School Adviser, you can submit questions to the Harvard Medical School Adviser at www.health.harvard.edu/adviser.