California senators are mulling a bill to require microstamping,

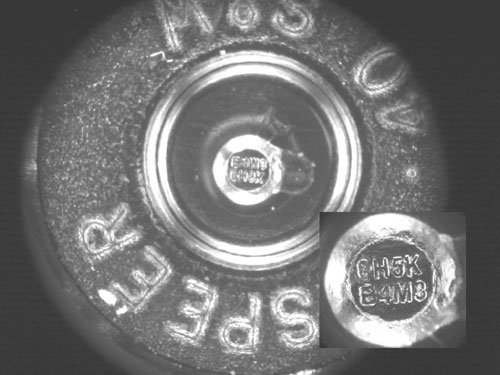

a new technology that imprints a tiny string of characters on each

cartridge a gun shells out.

Gilroy – California senators are mulling a bill to require microstamping, a new technology that imprints a tiny string of characters on each cartridge a gun shells out.

Supporters say the tool could clue in detectives on unsolved gun crimes, linking cartridges to a gun owner within hours. Opponents say it could inflate the price of firearms, and mislead detectives after stolen guns. And experts fret that the technology, though promising, is still too new and troubleshot to impose statewide.

“It gets a lot of attention because it has the word ‘guns’ written on it,” said Fred Tulleners, director of forensics at the University of California, Davis, where a graduate student conducted a small-scale test of microstamping this year. “But it’s not really ready to implement in prime time.”

Microstamping etches a unique identifying mark onto the cartridge of a gun, using the gun’s internal firing pin. The technique only works with semi-automatic handguns, which make up half the ballistics cases sent to the Santa Clara County crime lab, said criminalist Eric Barloewen. Microstamping has an edge over existing gun databases, which can only link casings to already collected guns: It can identify the registered gun used, whether or not the gun has been found.

The law has already passed the state Senate, and is up for discussion in the Assembly. State Assemblymembers Ana Caballero and John Laird support the bill, along with state senator Elaine Alquist, 62 California police chiefs, and the Police Officers Research Association of California, which represents more than 65,000 officers.

“It’s one more piece of evidence that we can look at to identify possible suspects,” said Stan Devlin, a board member of PORAC’s Central Coast Chapter. Devlin also works as a Gilroy police detective. “And if it turns out the gun was stolen, it’s one more piece of evidence to solve that theft.”

Guns would increase only a dollar or two in price, according to PORAC research, said Devlin. Others estimate the bill’s costs far higher. Tulleners doubts the technology could be deployed for less than $8 more per gun, because microstamping will only be installed in new guns manufactured after 2010. On a purchase of a $585 Walther P99, for example, a 9mm semiautomatic, the $8 would translate to only 1.4 percent of the purchase price.

Microstamping is only available from a single vendor, NanoMark Technologies in New Hampshire. NanoMark has promised to offer a royalty-free license for the patented technology, hoping to assauge fears of a monopoly. Tulleners remains skeptical.

Still, to Assemblywoman Caballero, even $8 is a decent price for the tool.

“Assuming for argument’s sake that it was $8,” she said, “the cost is minor in comparison to the benefits to society … It is not a restriction on guns. It’s not an attempt to limit the use of guns … It’s a very modest addition to the firing pin, that could give us some really good information.”

But that, too, is under dispute. Firing pins can break, and some guns use a repetitive firing pin that overwrites the microstamp, making it unreadable, said Tulleners. Other pins drag, oblitering the number. Barloewen noted that he can already link a bullet to a gun and cartridge case, reading the microscopic pressure marks the gun leaves on the bullet– though his analysis takes much longer than reading a microstamped number.

“With a single stroke of a file, you could eliminate that lead,” said Barloewen. “It also doesn’t address the millions of guns already circulating, or the fact that most people use stolen guns anyway.”

Devlin, referencing PORAC reseach, said if “bad guys/gals” stole a gun and filed away the microstamp, the firing pin would stop working.

“Sure, the bad guy/gal could go out and look for a new firing pin,” he said, “but that would take time and effort, and most won’t do that.”

The bill has its detractors: One of South County’s state senators, Abel Maldonado, voted against the bill in the state Senate. And mandatory microstamping is less popular among Sheriffs, who are elected, than police chiefs, who are appointed. Fourteen Sheriffs currently oppose the bill, while only two have registered their support. Caballero said the split likely occurs because police chiefs, who work in cities, deal with more handgun crime than Sheriffs, who patrol rural, unincorporated lands.

Neither Santa Clara County Sheriff Laurie Smith nor the police chiefs of Gilroy, Morgan Hill and San Jose have taken a stance on the microstamping law.

Yet to Tulleners, the political fuss has come too soon.

“The reality is, the thing needs more study,” he said. “It begs for a prototype project.”