This 2013 piece contains disputed material. Please see updated story here. —Editor

Sometimes, a slice of living history can go by unnoticed – be it your neighbor, the local beat cop, a volunteer counselor at a veterans’ clinic or a guy enjoying a free lunch at the Centennial Recreation Senior Center.

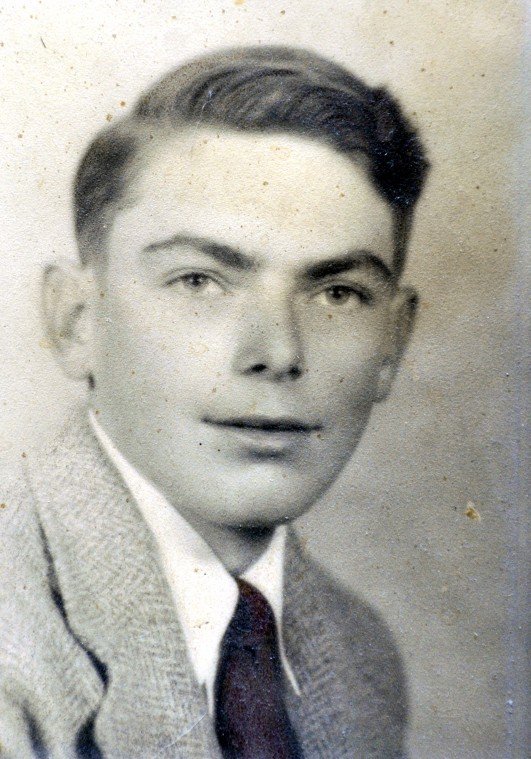

In this case, history takes the shape of a spry 87-year-old man named William Goehner, a Morgan Hill resident of 34 years, former cartographer, retired policeman, inventor, Santa Clara University School of Law alumni, self-taught mechanic, carpenter, veterans rights activist and storied World War II hero. The unassuming legend lives a quiet life these days, a divorcee of seven years who shares his home with one of his three sons and one of several grandchildren.

Morgan Hill residents may see the diminutive 5-foot-something octogenarian clad in his usual dark polyester slacks, button-down shirt and well-worn cane enjoying the company of his peers at the local YMCA-run senior center. He’s quick to smile and quicker to regale you with stories of the South County as it used to be, as well as wild wartime tales – one of which inspired a movie.

“I know I’m considered a hero, and I don’t feel like it, but most heroes don’t,” he said during a recorded video interview nine years ago for the Library of Congress. “They just say I am.”

Hollywood says so, too.

The Oscar-nominated black-and-white film, “The Frogmen” hit theaters in 1951, depicting the events surrounding a midnight “suicide” mission successfully led by Goehner 68 years ago in 1944. The mission – spearheaded by Goehner – entailed 30 specially trained men who dove into the night-dark depths of the Baltic Sea to plant explosives at the mouth of an underwater entrance to Germany’s biggest submarine base.

The sailors in Goehner’s unit, called the Underwater Demolition Team, earned the nickname “frogmen” because the fins they wore gave them an amphibious look. The military considers that corps a predecessor to today’s elite force, the Navy Seals.

“We tried bombing that base in the Baltic for months, but nothing took – the whole thing was under a mountain,” Goehner explains from his modest home off Monterey and Burnette avenues. “They sent us in there to destroy it directly.”

Goehner lost 19 of his 30 men that July night in 1944.

With the mission taking place years before technology made it easier and safer to navigate and breathe underwater, Goehner and his crew relied on fishing line to guide them back to the submarine, which served as their floating base. Anyone left behind by the end of countdown died from the blast or from the soundwave-induced concussion beneath the surface.

While Goehner survived the mission physically unscathed, losing 11 of his men left a lasting emotional scar.

“That was tough,” he said. “On all of us. Of course we became friends, we faced death together and only some of us escaped it.”

The deadly dive into enemy territory was one of 16 suicide missions Goehner volunteered for during his four-and-a-half year military career.

“Yes, volunteered,” he noted. “They left missions this dangerous in the hands of folks who signed up to do them. All volunteers.”

That volunteer spirit reflected his ethos from the start, when he enlisted in the Navy in early 1942 to avoid being drafted by the Army. Goehner said he wanted his service to be on his terms; his patriotic motivation.

The young Goehner was a string-bean 98 pounds at the time he signed his contract, measuring in at 5 feet 2 inches just four days shy of his 16th birthday.

A lot of thought went into that decision, he said. The Dec. 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor hit close to home, in terms of American lives lost and also because two days later a bunch of Goehner’s Japanese schoolmates got carted off to Bay Area internment camps.

“That made me very mad,” he said. “I wanted to do something good, and I knew there wasn’t much I could do here at home. Here I was helpless, still a kid. I wanted to channel this feeling into something I could do for my country.”

Goehner’s father, also a veteran, knew he couldn’t stop his son, so he agreed to help him out.

“I already graduated from Los Gatos High School, so my dad signed for me,” Goehner recounted. “I told him I’d be drafted anyway if he didn’t let me go. I wanted to join.”

The Navy gave Goehner his first look at the world and a chance to quickly climb the ranks. By the time he was 19, the diminutive sailor was named the youngest Lt. Commander in the entire Navy – a record that remains to this day. By the time of his medical discharge at the age of 20, he had earned four Purple Hearts, three Bronze Stars, three Silver Stars and, for his role in defeating the German U-boat base in the Baltic, the Navy Cross – the highest honor in his military branch. “U-boat” is an abbreviation of the German word “unterseeboot,” meaning “undersea boat” in English.

“When you’re young, you feel invincible,” Goehner said. “When you get wounded, you recover really quickly, so I didn’t put much thought into the worst outcome. I completed my missions because I love my country. It’s the best country in the world. I’d do it again if I could.”

That sense of invincibility gave him the nerve to take risks, think on his feet and stay calm under incredible pressure, he says. It’s the kind of go-with-your-gut impulsivity that saved his life during a reconnaissance mission on the German-occupied French shore and connected him with a man who’d later become his best friend.

In May of 1944, Goehner and a handful of sailors dressed in French civilian clothes got dropped off in enemy-occupied territory to stake out a shoreline the Americans planned to invade.

“We were there to see what we had to work with,” he recounted. “We’d memorized the aerial maps, which gave us an idea of the lay of the land.”

But Goehner missed the boat that collected his colleagues, which meant he’d have to lay low and wait for the next one to come around in two days.

The next morning, he was crawling around in the grass looking for a place to avoid detection until his men came back for him – it was springtime – when he heard a sound, glanced up and saw a German soldier holding a grenade, about to pull the pin out.

Goehner, still on his belly, quickly trained the barrel of his .45 automatic colt pistol between the German’s eyes.

“Were you born in the crazy town of Berlin?” Goehner asked in broken German.

The German laughed.

“You can’t speak German. Speak American,” he replied, in a perfect American accent.

The two started chatting and discovered that the German soldier had an aunt from Los Gatos, a woman Goehner happened to deliver a local paper to years before.

“So I say to him, ‘Look, I can’t be taken prisoner,’” Goehner said. “If I shoot you, your buddies will shoot me, then we’re both dead. If I take you prisoner, you swim back to base with me as a prisoner of war and you’re safe. Do you want liberty or do you want to die?”

The soldier swam back with Goehner, four miles offshore to the boat that carried them back to England the next day. They became fast friends, even long after the war.

It’s a friendship that defied the odds, just like Goehner.

The Navy told him he’d never be able to work after being discharged with charred hands, bullet wounds and other injuries sustained during combat. Goehner resolutely ignored those predictions, setting to work as a carpenter for his dad’s business right after the war.

Today, after a varied career in vastly different fields, Goehner makes time to make life more bearable for other veterans. You can find him, an unassuming visitor, at American Legion or Veterans of Foreign War posts in Gilroy or San Jose, chatting it up with his peers or informing other former military men and women of their rights and where to find the help they’re entitled to. He can also be spotted at South Bay outpatient clinics to exhort mentally troubled ex-soldiers to stay positive in spite of the trauma that followed them home.

“One thing a lot of people ask me is whether it hurts to get shot,” Goehner said. “I tell them nope, it only hurts right after, just when you realize what happened.”

The same goes for mental wounds, he continues. It’s a topic he broaches with younger veterans during his visit at local outpatient clinics that treat them.

“Sometimes it’s hard to figure out what’s in a person’s brain,” he tells another interviewer, Morgan Hill resident Emma Harris, during a taped conversation Goehner has saved at his home. “I tell them, ‘Look, you have some shortcomings from the service, but always do the best you can with what you have.’ ”