For nearly a century, the two blocks of Monterey Street south of 7th Street in Gilroy were home to two thriving groups of immigrant business owners—first Chinese and then Mexicans.

It was a vibrant part of the small city where racial segregation forced a concentration of entrepreneurship and wild-west lawlessness mixed with foreign languages, cultures, food, and religions in a unique blend of energy often overlooked by the community’s traditional tales of white-bread social clubs, bankers, and ranchers north of 7th Street.

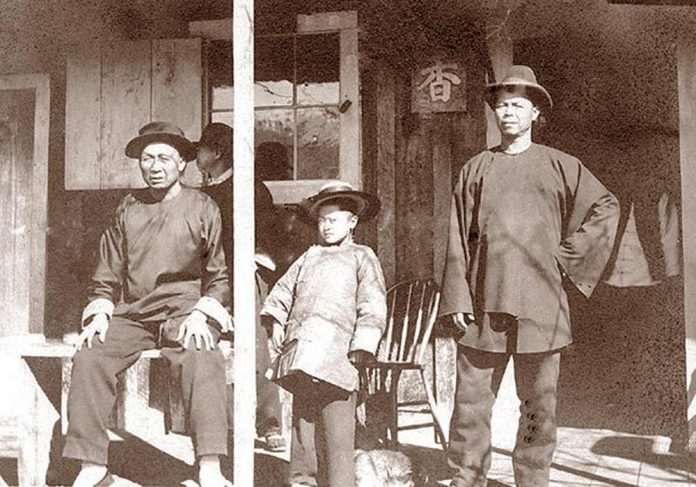

Little evidence remains of the first residents of this stretch of Monterey Street, which was one of the Bay Area’s first “Chinatowns.”

Beginning in the late 19th century and continuing to World War II, opium gardens, gambling halls, restaurants, even brothels, offered exotic options for visitors traveling between Los Angeles and San Francisco.

The old Cherry Blossom Hotel, its second iteration still standing, was a focal point. Much of the rest of the block was destroyed by fire.

Chinese workers had immigrated to the Bay Area to help build railroads and work in gold mines, tobacco fields and growing orchards. By the late 1800s, local historians told the Gilroy Dispatch in 2004 that nearly 1,000 Chinese immigrants lived in Gilroy, most in a small section of town surrounding the Chinatown business district.

The Consolidated Tobacco Company of Gilroy at one point employed 900 Chinese immigrant workers, rolling 1 million cigars a month, according to historians. The world’s largest cigar factory was built on Monterey Street near the railroad yard.

By the 1870s, the majority of the agricultural workers in California were Chinese. During this time, Gilroy’s Chinatown boomed. Chinese who did not work on farms, owned or worked at businesses along Monterey Street, which included laundries, restaurants, saloons, gambling houses, drug retreats and at least one brothel.

New immigration laws, however, would make assimilation difficult for the Chinese workers. Violence often filtered south from San Francisco, where Asian gangs ruled many businesses and neighborhoods by extortion. Many Chinese moved to work on farms in the Central Valley.

After World War Two, new generations of farm workers, and new groups of veterans of Mexican heritage moved to California, and to Monterey Street south of 7th Street.

One Gilroy man offered a vivid account of what would occur south of 7th Street,in the decades following World War Two—the transformation of Chinatown to Poker Town.

After two years serving in a tank in General Patton’s 3rd Armored Division in Europe, Herman Garcia came to California to marry his Texas childhood sweetheart, Mary Ruiz. Mary’s parents had bought what was then the largest apartment building in Gilroy, at the corner of 7th and Eigleberry streets. He and Mary got married, moved into the apartment building and started a family.

He named his first born son Herman Jr., and eventually would have five more children. In an interview, Herman Jr. told of the years growing up in the Ruiz-owned Guadalupe apartments, and playing with friends among the growing numbers of Mexican-American families moving to Gilroy, mostly for agriculture-related work. He and his friends went to St. Mary’s school, and played in the downtown neighborhood.

His father opened a small business, a neighborhood market, on 6th Street, the site of Gilroy’s first post office, and called it Post Office Market, where he offered custom-butchered meats. But on weekend evenings, as his son tells it, Herman Sr parlayed the poker skills he learned in the Army into a job as a dealer in a $5,000-buy-in, no-limit card club on Monterey Street between 6th and 7th streets, “where all the local high rollers went to gamble,” according to his son. That card room attracted ranchers and business owners from all around Gilroy. “This was a big cattle hub in the late ‘40s and ‘50s,” Herman said.

Eventually, his father sold the market, leased a building opposite the Gilroy train station, and opened his own card club, Garcia’s Club, in 1952. His club served mostly Mexican workers, many of them temporary workers in the bracero program, who found a place to play pool, play $2-buy-in poker and eat Mary Herman’s breakfasts.

Poker Town was born.

Garcia’s club became wildly popular in the 50s and 60s and Herman Sr., soon would buy a half-dozen adjoining buildings. His son became so adept at cards that by the time he was a student in the first class of Gavilan College, he was winning at poker. “It was like the Wild West,” he said, with constant street fights and threats from Bay Area gangs.

Herman Jr. turned poker into a career, traveling in the 1970s as “The California Kid ” all across California in a white chauffeur-driven Lincoln, attracting crowds and players to his poker prowess.

Meanwhile, on 7th Street, an Hispanic Chamber of Commerce was formed, and Hispanic-owned startups opened in the Garcia-owned buildings. A restaurant added to Garcia’s club attracted clientele from all over the city, and gradually racial and societal barriers broke down.

The Guadalupe Apartments burned down, leaving what is now a vacant lot. Garcia’s Club has been closed for more than 20 years, after Herman Jr. retired from poker to dedicate his life to run a non-profit that cleans up the Pajaro Valley.