Gilroy

– Like many of his classmates at Gilroy High School, Zachary, a

sophomore, uses his cell phone to talk and text message his friends

and family.

But when test time rolls around, Zachary

– and some of his friends – use their cell phones for something

else: to cheat.

Gilroy – Like many of his classmates at Gilroy High School, Zachary, a sophomore, uses his cell phone to talk and text message his friends and family.

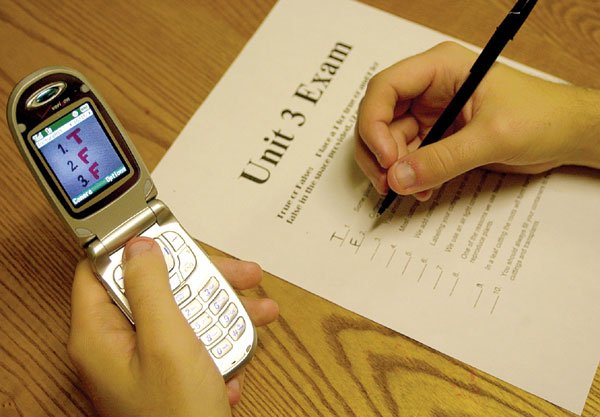

But when test time rolls around, Zachary – and some of his friends – use their cell phones for something else: to cheat.

“It’s just easier and teachers don’t notice,” Zachary said while hanging out near the quad during lunch last week. “I only cheat when I have no idea what the answer is, and I think I’m gonna fail if I don’t find out the right answers.”

While sneaking a peek at the nearest student’s test once was the most common way to cheat, high-technology gadgets are making it easier for students to inconspicuously get answers fast.

In a matter of seconds and virtually silently, students can use their cell phones to send answers to test questions to each other, via either close-up photographs of test questions with camera phones or, more commonly, text messaging.

Students said cheating with text messages works best with multiple choice questions that are common in math and science tests. English and history tests are a little harder because they require essay answers, but students still can type an abbreviated version of the essay questions into their phones and later pass them on to friends who still have to take the test. Or, students can use camera phones to take photos of at least part of the essay questions and fill in the blanks later.

In 2002, a state law passed that permits cell phones on school campuses and grants individual districts authoritative oversight. GHS does not have an overriding school policy on cheating. Rather, teachers create their own rules and consequences for cheating, the most common being a zero grade on the test, a call to the parents and perhaps detention.

Even students who aren’t tech savvy find ways to get the right answers. Amy Blunder, a junior, said several of her female friends have devised their own system of cheating. They’ll wear skirts on the day of a test, then sit next to their friends while taking the test. When one friend doesn’t know the answer to a question, she’ll write the number of the question on her upper thigh, get a friend’s attention and show her the number. The friend will respond by writing the answer on her thigh.

Many teachers said they’ve wisened up over the past couple of years and have become much more aware of cheating in general, especially with cell phones. A zero, or very low tolerance for cell phones in the classroom to begin with, helps ensure students refrain from cell phone use at all. Students are warned to keep cell phones turned off and in their backpacks while in class.

“I had a problem with students and cell phones last year, so this year, if I see them, I’ll take it away and give it back after the bell,” said Un-Young Lamborn, an advanced math teacher. “If it happens again, I’ll send the student to the discipline office and call their parents.”

But some students think otherwise, such as one of Zachary’s friends, Joseph, who said teachers are “oblivious” to cell phone cheating. Many students have become so adept at manipulating the keypads – and the phones themselves have become so small – that it’s easy to miss students glancing under their desk every few minutes to type in or send a text message or photo, especially with an average class size of 31 students.

Mani Corzo, assistant principal in charge of discipline at GHS, said one of the best defenses against cell phone cheating is for teachers to carefully monitor their classrooms, especially during tests. But even the most vigilant teachers can miss discreet cheating, he said.

“I would say 90 percent of the time, it’s impossible to see, even for the teachers who are very good about walking around and checking on their students,” he said. “There probably could be more control in the classroom on everyone’s part, but teachers can’t see everything.”

As uncool as some students might feel without their cell phones close at hand, GHS principal Bob Bravo said the high school might consider banning cell phones altogether.

“From my talks with teachers, there doesn’t seem to be evidence that cheating has become worse, but it has been and remains a problem,” Bravo said. “We have not been able to come up with a way of addressing this concern without looking at a cell phone ban.”

But that would be a difficult battle to win, Corzo said. Banning anything on school grounds would need to be justified as a safety issue, such as banning knives, and it would be hard to make the connection between student safety and cell phones, Corzo said. If anything, cell phones can serve as safety aides, facilitating communication in emergency situations.

And for many students, cell phones aren’t just a social in, but a way for parents to keep tabs on where their kids are and what they’re doing.

“I know of so many parents who give cell phones to their kids now,” Bravo said. “Cell phones are becoming as common as pens and pencils.”

Edith Guzman, a Spanish teacher, said she hasn’t caught students using cell phones to cheat, but she said she wouldn’t be surprised if it was happening. Despite disciplinary action and constant warnings, many students still have cell phones out during class, Guzman said, forcing teachers to be especially on guard for cheating.

“It used to be that we’d have to watch for answers written on hands or on another piece of paper,” she said. “Now it’s cell phones.”

Biology teacher Julie McLaughlin said during tests, she sits in the back of the classroom and walks around to make sure students aren’t cheating. Like other teachers, McLaughlin also distributes different versions of the same test, rendering text messaging the correct answers almost impossible.

But even some teachers who are confident cell phone cheating isn’t a problem in their classrooms perhaps are being misled, said marine science and Advanced Placement biology teacher Jeff Manker.

“Many times, it’s happening in the classes where the classroom is out of control, so the teacher doesn’t know it’s happening,” said Manker, a 19-year veteran. “There are a lot of classes out of control, and I used to be one of those teachers, so I know what it’s like. A lot happens that you don’t know about.”