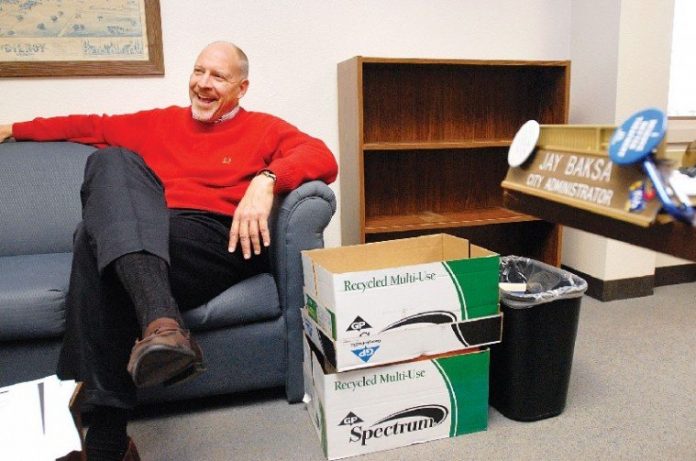

City Administrator Jay Baksa will retire Friday after 24 years

as the man with the plan.

City Administrator Jay Baksa will retire Friday after 24 years as the man with the plan.

As the longest-serving city administrator in Santa Clara County, Baksa has earned a reputation for foresight and number crunching. His planning and signature five-year budgets have helped keep Gilroy in the black as other cities’ “wish list” budgets have drained their funds periodically during the past 20 years.

All this will likely be Baksa’s Clark Kent reputation, though, as hundreds of residents know him instead as “Coach Baksa.” Over the years he said he has coached more than 1,100 youth sports games, from basketball to soccer, whenever he was not donning a tie to steer the city through an environmental scandal, plan its infrastructure, remodel its downtown, build a new police headquarters or widen Santa Teresa Boulevard.

While retirement means Baksa won’t have to worry about showering between Gilroy High School junior-varsity basketball practices and city council meetings, it also means he can fulfill his desire to visit every Civil War battle site. He has about 25 under his belt and hundreds more to go, he said, adding that his passion probably stems from the historical pit-stops that his father mandated during childhood road trips.

Imagining the thousands of corpses stacked 4- to 5-feet tall on the battlefield in Spotsylvania, Va., puts the daily struggles at City Hall in perspective, Baksa said. But when the 56-year-old first came to Gilroy in 1983 after nearly 10 years of experience in Cortez, Colo., and Delaware, Ohio, Baksa suddenly found himself in the midst of another messy battle.

Just an hour into his first day on the job in July 1983, Baksa learned that the former city manager, Fred Wood, and other top-level employees had orchestrated and covered up sewage dumping into a local creek after two years of heavy rain overwhelmed the system.

Within three weeks, Baksa was interviewing city employees under oath to learn what they knew about the situation. Within three months, the state imposed a building moratorium on Gilroy. And over the next few years, Baksa found himself testifying in front of district attorneys, the state attorney general and countless other agencies as he struggled to clean up an environmental mess and repair City Hall’s tarnished reputation. The building moratorium that hobbled Gilroy financially through the 1980s was finally lifted in 1991 with the completion of a new sewer plant that the city jointly operates with Morgan Hill.

“Now our plant is one of the best in the state. It’s an example of how to do things right,” Baksa said of the South County Regional Wastewater Authority.

Sewergate was far from Baksa’s only accomplishment. He volunteers for the Gilroy Rotary Club and Leadership Gilroy. After his retirement, he will host training seminars for the International City Managers Association and the League of California Cities, for which he will also be a “range rider”: a volunteer advisor for city administrators in Santa Cruz, Monterey and San Benito counties.

They should be so lucky, said Mayor Al Pinheiro.

“People would be crazy in other communities not to use his strength somehow,” Pinheiro said.

Roberta Hughan agreed.

“He made my life easy when I was mayor because I didn’t have to worry about the budget,” said Hughan, the mayor from 1983 to 1991 who worked with Baksa to design the city’s growth control system that is still in place.

“He always said, ‘You should never handle a piece of paper twice,’ ” she said.

Another Baksa-ism has been customer service and his “Do it” mantra that he said has encouraged city employees to be creative and just do it, as long as it’s a good idea, of course. This flexible-yet-firm leadership has defined his tenure, during which Gilroy doubled in size from 24,000 to nearly 50,000 residents. Sales tax revenues dating back to 1983 were not readily available, but they have risen from $6.6 million in 1996 to more than $14 million in 2006, according to figures from the Gilroy Economic Development Corporation.

Meanwhile City Hall grew from 126 employees to 296, and along with more employees came more diversity. Former Councilman Charlie Morales pushed for increased diversity during his time on the council from 1993 to 2005.

“The diversity we now have is really what Jay took to heart,” Morales said. “That’s a big milestone we came across.”

As Baksa’s right-hand woman and a city employee since 1982, Karen Pogue has seen it all. The administrative secretary said she will remember the plays and outdoor hikes she enjoyed with her boss and colleagues, but most of all, she will miss his playful personality that emerged every Halloween, most memorably in the form of a carpet-chested Austin Powers complete with buck teeth.

This is the side of Baksa that his family knows, and he said he always made sure to leave his work at home so that Vicki, his wife of 32 years, would remain his wife, not a sounding board. He also relished raising his three sons: Jay, 28; Bobby, 25; and Tucker, 22. They all played sports growing up in Gilroy, much to the delight of Baksa, a former football and basketball player who said it’s impossible to watch too much of the Kansas City Jayhawks, his alma mater.

Many others vouched for the ascetic, focused exterior that covers Baksa’s lighter side. Santa Clara County Supervisor and former Gilroy mayor Don Gage said he remembered thinking Baksa was mature beyond his years when he first came to the city, back when he still had hair, Gage said jokingly.

“Jay brought accountability to the city. If you asked him a question, he never had to say, ‘Let me get back to you.’ He had the answer. He had his finger on the pulse of the city at all times,” Gage said.

Former councilwoman and local historical guru Connie Rogers agreed.

“Jay instilled confidence in his employees and always provided alternatives to the city council. He gave us a we-can-do-this feeling,” Rogers said in an allusion to Baksa’s budgeting system. But it was the one-on-one lunches Rogers had with Baksa at various city parks that she said she really enjoyed, as did dozens of other councilmembers who said it gave them an opportunity to build rapport and understand the city.

Councilman Bob Dillon said he bonded with Baksa when he found at that both their fathers were working-class guys from Ohio who wanted to give their sons more than the Greatest Generation could offer. Dillon pointed to Baksa’s successful luring of Wal-Mart and the recent renovation of downtown as two achievements that have given generations of Gilroyans a better place to live.

Still, there are those who have criticized Baksa for over-stepping his bounds at times. Councilman Perry Woodward frequently laments a “culture of secrecy” at City Hall, and Councilman Craig Gartman has complained about city staff infringing on the council’s policy-making authority. Woodward was only 14 years old when Baksa came to Gilroy, but he has since learned that the “master of the city budget” understands city finances better than anyone else. Pinheiro said this is because Baksa never counts a dollar until he has two.

Now Baksa will be counting fouls and baskets on the court, where his true self emerges.