Out in a portable classroom pressed up against a chain-link

fence on the north side of Las Animas Elementary School, a teacher

is waging a war against declining district math scores. The battle

starts fresh every morning at 7 and, for many of the students she

teaches, will not end until they finish college.

Gilroy – Out in a portable classroom pressed up against a chain-link fence on the north side of Las Animas Elementary School, a teacher is waging a war against declining district math scores. The battle starts fresh every morning at 7 and, for many of the students she teaches, will not end until they finish college.

“I need to fix the problem now so that when I let them go, I don’t need to worry about them.” said third-grade teacher Carmen Kotto.

Something for Everyone

When Kotto learned that some of her past students were falling behind their coursework – as are fourth-, fifth- and sixth-graders nationwide – she invited them to a custom after-school intervention program. The end goal for students is clear.

“Today is day one for college,” she said to her class. “No, today is day 300-something for getting ready for college.”

Kotto is backing up this assertion through 17 hours of instruction that she offers to 30 students – 19 of whom are in her current class and 11 of whom are past students. She noticed the older kids, despite being proficient when they left her class, were falling behind in fourth, fifth and sixth grades. Feeling an attachment to them, she invited them to get extra help at the end of the school day.

Within a month of starting the program, she could take in no more students. She also had begun branching out, tutoring the older students in reading as well. The hard work has paid off, with almost all of them regaining their proficiency in math and more than half substantially improved their English scores on a district test. This comes despite many being overwhelmingly English language learners and from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

Kotto’s commitment did not stop at the students. Having spent $4,000 of her money to purchase eight computers and learning software to run on it, Kotto invited parents, largely immigrants from Mexico, to come in the afternoon to use the technology to practice their English.

“This is a gift from god, this program,” Angela Morera said in Spanish, fighting back tears.

Her third-grade son, who came to the United States when he was in kindergarten, was lost in the three years before he came to Kotto’s class because neither Morera nor her husband could speak English and thus help him with his homework.

“He tried and tried and tried” to do his work, she said. “It’s been a trauma because we weren’t able to teach him.”

Morera now practices her English not only on the computer in Kotto’s class after school ends, but also with her son when they are at home.

“It’s been a great success,” she said.

Any Means Necessary

“Some kids have to move to get it,” Kotto said “Some have to touch it, feel it, taste it.”

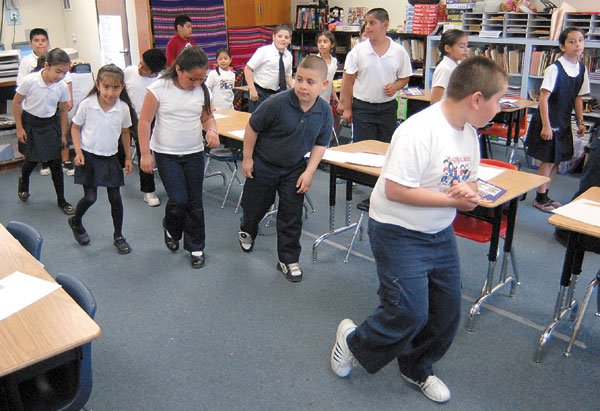

Watching her third-grade class is like viewing a videotape – and she has the remote control. At one moment, the students will be shaking their hips to a samba or tapping their feet on the floor to the electric slide, all smiles and movement. The next moment, they are standing silent, hands at their sides, in matching dark blue pants or skirts and white tops – a uniform only her class wears. Suddenly – on her signal – they will break into a chant about their advanced level of mathematics and, just as suddenly – as she closes her hand together – they will be silent.

In an attempt to cater to these different learning styles, Kotto uses hand gestures, dances, songs and rhymes to get her students to remember material. She also enforces a strict dress code to ensure no students feel they are at a disadvantage because they cannot afford a certain type of clothing.

Understanding that money will be an issue for many of these students, Kotto strives to promote money management through the use of fake money in her classroom. Students are given $100 for showing up to class, handing in homework, wearing their uniform and other displays of good behavior. They can then trade money in for prizes such as pencil erasers and stickers. However, they must pay $1,500 in rent each month and anywhere from $100 to $500 for acting up in class.

“Money is not a punishment, money is a reward,” Kotto said.

However, one parent saw money not only as a punishment, but as an example of Kotto’s draconian teaching style. This parent – who wanted to remain nameless to protect her daughter, who was transferred out of Kotto’s class in January – said Kotto’s strict rules and homework on weekends crossed a line.

“I’m very concerned about children,” the mother said. “This mental abuse is more damaging than the physical.”

Kotto recognizes that she is strict, not only with the students but also with the parents.

“I’ve got to push them to get them to not drop out of high school,” she said. “If I’m wimpy with them, it’s not going to help them. It’s all with love.”

In the end, the conflict was the result of incompatibility, said Silvia Reyes, principal of Las Animas. Moving the child out of the class solved this problem.

“The needs of that particular student and that particular parent, their needs were met,” she said.

Money Talks

Some parents see the strict rules in Kotto’s class as both a benefit and a sign of her caring for the students.

“I’m so really happy because this teacher is really supportive for the kids and she has excellent communication with the parents,” said parent Linda Delgadillo. “They get the academic support but they also get the other support with the discipline.”

Regardless of whether parents like it, the strict policies are producing results. Math proficiency in Kotto’s third-grade students went from 35 to 71 percent during the past eight months. This is above the district rate of 63 percent last year.

If this was not enough to cement her image as a caring teacher, Kotto has pledged to pay for college for a past student, now a fourth-grader, whose family would not be able to afford it. She has already opened a savings account and has been putting aside part of her paycheck for about a year.

College starts in elementary school, Kotto said, and she will make sure her students get there. Once they leave her classroom, they do not cease to be her student.

“They’re in forever,” she said.