Q: I have a prolapsed mitral valve, but I don’t have a heart

murmur. I heard about a new study that found that some people with

mitral valve problems should have surgery to repair the valve, even

if they don’t have symptoms. Should I ask my doctor if I need this

surgery?

Q: I have a prolapsed mitral valve, but I don’t have a heart murmur. I heard about a new study that found that some people with mitral valve problems should have surgery to repair the valve, even if they don’t have symptoms. Should I ask my doctor if I need this surgery?

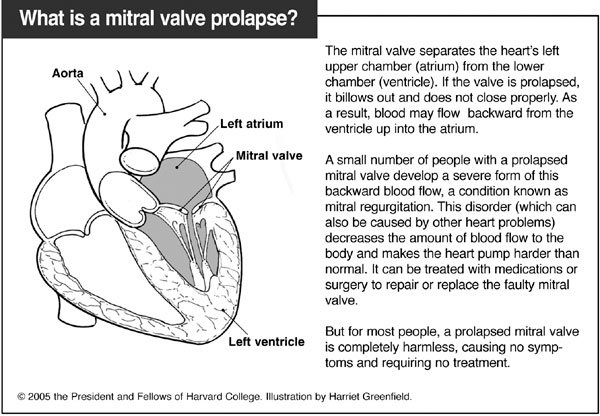

A: Mitral valve prolapse is a common and usually harmless condition, affecting about 5 percent of people in the United States. The mitral valve separates the two chambers on the left side of your heart – the left atrium and the left ventricle.

If the valve is prolapsed, the two flaps of tissue which make up the valve billow out and don’t close properly. That’s why the condition is also known as a “floppy” or “billowing” mitral valve.

When that happens, blood can flow backward, from the ventricle up into the atrium. This backward flow is called regurgitation.

A small amount of backward flow is normal and doesn’t cause any symptoms. But if there’s a great deal of regurgitation, it can cause fatigue and breathlessness, and stress the left ventricle.

Using a stethoscope, a doctor can usually hear distinctive sounds, known as clicks and murmurs, caused by the regurgitation.

People with significant mitral valve regurgitation need to take antibiotics before undergoing certain dental or medical procedures.

That’s because such procedures can introduce bacteria into the bloodstream. The bacteria can contaminate a damaged mitral valve, causing an infection of the heart called endocarditis.

The procedures include:

n dental work that causes bleeding (including a cleaning);

n examination of the colon or urinary system using a tiny camera on the end of a flexible tube;

n some operations on the lungs, digestive system or urinary tract, especially gall bladder removal and prostate surgery.

Sometimes, people with severe mitral valve regurgitation need surgery to replace the valves.

But it’s been hard to decide who should have it and the best time to do it.

Traditionally, doctors have recommended surgery if person has symptoms such as shortness of breath or evidence of a weak left ventricle.

But waiting until symptoms develop before fixing the mitral valve can be risky.

During the waiting time, the left ventricle may weaken so much that it won’t work right even after the faulty valve has been replaced.

The study you’re probably referring to appeared earlier this year in the New England Journal of Medicine.

It involved examining the mitral valve with an echocardiogram, which uses sound waves to create moving images of the heart.

Using this simple, painless test helps identify people with mitral valve regurgitation who might benefit from surgery before they develop symptoms.

Researchers found that people with pencil-width holes in their mitral valves were five times more likely to die of a heart problem or develop heart failure or an irregular heartbeat than those with mild leakage.

However, the results don’t really apply to you. Many of the people in the study had mitral valve problems other than mitral valve prolapse.

Also, the people included in the study had enough leakage across the mitral valve to cause a definite murmur, even though they didn’t have symptoms.

For people like you, who don’t have a murmur (and so have little leakage across the mitral valve), the risk of developing any problems is very low.

You also don’t need to take antibiotics prior to the above-mentioned procedures.

Still, it’s a good idea to keep in touch with your doctor. Let him or her listen to your heart every year or so to check for the development of a murmur, indicating mitral regurgitation. If that happens, routine echocardiograms to measure the amount of leakage through the valve and to see if your left ventricle is getting larger would be useful.

Submit questions to the Harvard Medical School Adviser at www.health.harvard.edu/adviser. Unfortunately, personal responses are not possible.