One day, Tenth Street could be reincarnated as a gateway corridor funneling U.S. Highway 101 traffic to downtown Gilroy.

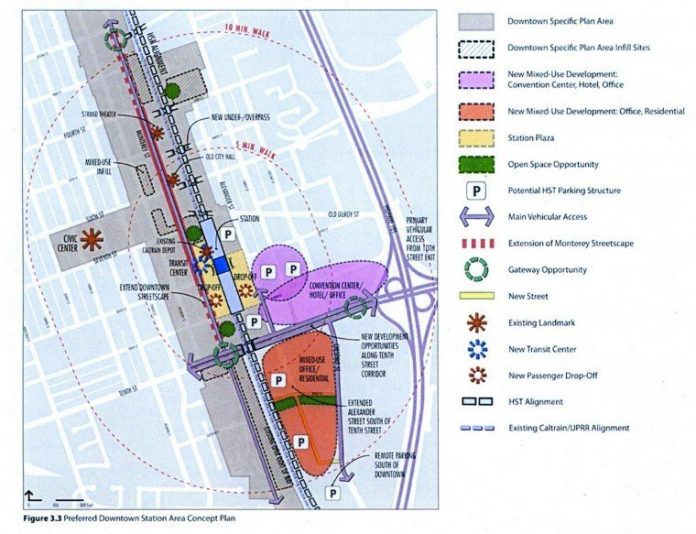

It would lead to a bustling high-speed rail station, complete with convention center, hotel, offices, a multi-use plaza and a “small, independent mix” of additional businesses such as coffee shops, retail spaces, restaurants and bookstores.

The pedestrian-friendly transit district would have a “symbiotic relationship” to the bullet train station and be a complementary extension to existing downtown businesses, according to a $200,000 High-Speed Rail Visioning Study that began in April 2011.

Of course, that’s if the California High-Speed Rail Authority adheres to the City of Gilroy’s location preference when it comes to erecting a $98.5 billion, 800-mile rail line with daily stops in the Garlic Capital.

The city is eyeing somewhere between Seventh and 10th streets on Monterey for a potential station plaza, with surrounding infrastructure expanding east along 10th Street.

However, “the city does not have final authority like it does on other things that get built in the city,” reminded City Transportation Engineer Don Dey during a special high-speed rail meeting Monday evening. “You’ll get pieces of the project, and you’ll be asked to respond, but you’ll never see ‘City of Gilroy: This is how everything fits together.’ You will only get it in a piecemeal process,” Dey said.

In a 5-2 vote cementing the city’s recommendation for a bullet train station, a majority of councilmembers made it clear they want the train downtown, rather than east of the Gilroy Outlets in prime agricultural land. City Council also threw in the caveat that an aerial alignment would be unacceptable.

Holders of the two opposing votes – Councilmen Dion Bracco and Bob Dillon – want the controversial and expensive transit endeavor to bypass Gilroy and plummet off a cliff.

“I think it’s all just a show to make us think we have a say,” said Bracco, who remained silent throughout Monday’s meeting but spoke to the Dispatch Tuesday. “Cities today are like a bunch of dogs underneath the table waiting for the scraps to drop. That’s what HSR is: Everybody waiting to see if the government is going to drop any money into their community.”

Dillon, on occasion, has referred to the high-speed rail as a “giant boondoggle” that should have a stake driven through its heart.

With the exception of unflinching opposition from a stoic Bracco and Dillon toward the entire project, every council member expressed disapproval for an east side alignment. Councilman Peter Leroe-Munoz touched on environmental concerns; Councilman Peter Arellano said he wanted to focus on funneling more economic activity into the downtown; not away from it.

“I didn’t hear anything tonight to sway me east of the Outlets,” he said. “Let’s keep Gilroy whole in the middle.”

The city will study the possibilities of a modified at-grade or downtown trench alignment.

Following months of swirling questions and ongoing discussion on whether the passenger train system – which could whisk riders at speeds of up to 220 mph between California’s major cities from Los Angeles to San Francisco – will ever come to fruition, two things are clear: The train isn’t going away, according to Dey, but council members say it’s not arriving anytime soon.

“It’s very likely to happen. The question is when,” said Councilman Perry Woodward Tuesday. “It’s not likely I’ll ever ride the high-speed rail, but my daughters who are 5 and 3 likely will.”

The CHSRA revealed in its November business plan the pricey project won’t be up and running until 2033 (nine years later than previously projected); “it will probably come decades later,” said Woodward.

As the bullet train “will be an on and off again discussion that we will continue to have for the rest of our lives,” Woodward believes the odds of seeing the locomotive behemoth up and running by 2033 are less than 10 percent.

Distant as those train whistles seem, there will come a time when California’s roadways won’t be able to accommodate surmounting traffic congestion near airports, in big cities and commuter-heavy highways, Woodward said.

Hence, “the planning we’re doing now is not wasted,” he argued.

Downtown developer Gary Walton is even less confident in the project.

If he had to choose, Walton prefers an out-of-sight trench alignment, but “I think it’s so far down the road, it doesn’t make a difference,” he said Thursday. “I just don’t think (the project) is cost effective right now.”

Walton said he would rather see the state put the money into local transportation.

Monday’s recommendation marks the culmination of a prognostic $200,000 station area visioning study, which was funded through $50,000 from the City of Gilroy and a $150,000 grant from the Valley Transportation Authority grant. The study began almost a year ago in April.

The objective was two-fold: To engage the community with an outreach program explaining the options for two possible station locations in Gilroy, and to provide City Council with a plan outlining the major differences between the two options.

Concerning the impacts of a bullet train dissecting downtown’s landscape, it all depends on the route of construction. Whereas an at-grade alignment (a modification to Gilroy’s existing railway) would effect approximately 12 buildings, a downtown trench alignment would effect 23 buildings, two commercial structures and five residential structures, according to the city’s high-speed rail visioning study.

Noise shouldn’t be an issue, according to David Early, founder of DC&E Consulting that conducted the high-speed rail visioning study. Because it’s going so fast, he explained the bullet train has an “otherwordly sound” that makes it quieter than the average train.

“It’s so well engineered that it’s more of a swoosh sound,” said Early.

A number a positive effects are outlined in the study relative to a downtown location, including the creation of 4,800 jobs and ongoing economic stimulus associated with hotel and conference facility developments envisioned for the station.

“The anticipated benefits to the neighborhood are likely to be an increased number of jobs, a more vital downtown with more shopping and recreational opportunities and improved public transit access to the region and beyond,” the study states. “It is likely that the new public investment in an HSR station would provide a valuable catalystic effect in the downtown area once improvements are in place.”

Promises of growth and prosperity aside, Bracco maintains the state is dreaming up a vision it can’t afford.

“Even if they go through with this thing, how are they going to pay for it?” he said. “The general fund of California is bankrupt.”

Woodward agrees: Nothing is going to happen until the government gets its fiscal house in order.

“I look at Congress and how dysfunctional it is,” he mused. “I don’t think anything is going to happen until there’s a change at the national and state level.”

Criticism for the project has spiked since voters approved roughly $9 billion in bonds in 2008 to partially support what was then advertised as a $33 billion project that has now climbed to $98.5 billion.

Still, there’s no sign of easing the brakes at this point, according to Dey. He made a point during Monday’s staff report to underline the importance of staying in tune with the process, lest Gilroy get left behind when it comes to important high-speed rail decisions and funding allocations from regional agencies.

“California Governor Jerry Brown has declared his intention to make this project a reality,” Dey cautioned to councilmembers. “From my stance, there is no evidence that HSR is slowing its environmental and design effort in Gilroy. There’s still a lot of effort going on behind the scenes … we need to be prepared to respond to the HSR environmental impact review so we can stand up and look out for Gilroy’s best interest.”

The next two planning phases, for which there is currently is no timeline, includes the development of a Gilroy’s Station Area Specific Plan. This will be followed by the implementation phase, which involves the preparation of an environmental impact report, adoption of the Station Area Specific Plan and adopting the general plan/zoning code amendments.