Arrests in Gilroy may soon be accompanied by an electronic “third eye” that objectively monitors the scene, keeping recorded tabs on the actions of the suspect, as well as the officers on the job.

The 19 clip-on cameras Gilroy police purchased with federal grant funds earlier this summer are currently being tested on several officers in the field while the police union negotiates with the department on fair and “reasonable” guidelines for their use.

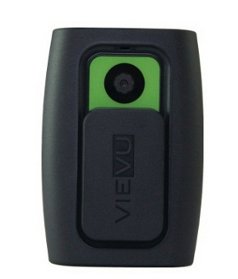

The LE2 Vievu body cameras, which were purchased in July with a $15,827 Edward Byrne Memorial Justice Assistance Grant at no cost to the Gilroy Police Department, are cell-phone sized devices that clip to an officer’s uniform to capture audio and color video recordings of incidents, according to Police Sgt. Chad Gallacinao.

“We hope to use video evidence in court prosecutions to make that process run efficiently, to give an accurate depiction of what happened. Hopefully it will reduce potential civil liability and be able to aid us in the reviewing of alleged officer misconduct,” Gallacinao said.

After the GPD’s traffic unit implemented five of these cameras a year ago, administration decided to make it a priority and applied for a grant to purchase more. The traffic unit “routinely” use their camera footage as evidence in traffic court, Gallacinao said.

Patrol officers are currently using the new cameras intermittently during a “testing” phase of the equipment while the Police Officers Association and department administration negotiate over when and how officers will be required to use the cameras, as the union has expressed some concern about possible repercussions.

“We’re trying to get as much feedback from officers using them as we can before we establish permanent guidelines,” Gallacinao said.

Tentatively, Gallacinao said officers will be required to have the cameras on during all patrol and pedestrian stops, as well as any other calls they tend to – unless operating the camera threatens the officer’s safety.

“The last thing we’d ever ask an officer to do is violate their safety to turn on some piece of equipment. But if safety is not an issue, it should be on,” he said.

Gallacinao said the cameras are very simple to turn on and easy to keep activated, but when it comes to life and death, even a split second to turn on a camera could be too risky.

Vievu, founded in 2007, has sold cameras to more than 2,000 law enforcement agencies across the county, according to their website.

The Campbell Police Department has been using Vievu body cameras for three years, said Campbell Police Sgt. Joe Cefalu. With every patrol officer having a camera, Cefalu said that the tapes are used as court evidence all the time.

“The District Attorney routinely asks us for video evidence,” Cefalu said. “It’s been extremely successful and saved us countless hours and money in investigation costs and lawsuits from people who have tried to file frivolous cases. When it’s all on video, it puts a lot of questions to rest right away.”

Cefalu said that officers are required to have their body cameras on anytime police are at a scene they think could lead to an arrest, so routine calls for service are excluded from the requirement.

Elsewhere, the cameras have presented legal disputes. In Oakland last year, an officer who fatally shot a suspect while wearing a body camera was not allowed to view the tapes before appearing in court, despite his request to do so – a policy the Oakland Police Department has since tweaked through negotiations with their union.

Sgt. Jason Smith, president of the Gilroy POA said the cameras are a bit of a double-edged sword, in that they could be very helpful or disadvantageous, depending on the situation.

“There’s good and bad behind them. The good is that they can document an encounter. The bad is the narrow scope of the camera, which could present a slanted view in court,” Smith said. “Necks, they swivel and can see much more than a camera will record,” he said.

Smith said the union is actively negotiating the guidelines for the cameras with administration and pushing for what he called a “reasonable standard” in the language for camera use requirements.

“It needs to be understood that in every given situation it might not be possible to have them on. If you had language that said, ‘You must use it,’ it’s not going to work because say you’re downloading footage and you get called out, are you going to wait for it to finish downloading to go to that call?” Smith said.

Smith said he will have more details in a few months, when the POA forms a more official position on their preferred camera guidelines.

Officers will take the camera back to the office after their shift in the field and download the video footage on to a shared server.

Pointing to the reality that technology doesn’t always work the way it’s supposed to, Smith said that in some situations they could be very effective, while in others, they could be more trouble than they’re worth.

But Smith conceded that police technology is necessary in the digital age, and that a video recorder is really a small step from the types of audio recordings for interviews and patrol car cameras that have been implemented for years.

“As an officer, sometimes you’re not trusted by the public, and that’s why you’re needing to do things like this. That part is disheartening. But at the same time, this could really help us,” he said.

Cameras could, in fact, put to rest unwarranted claims for police brutality in court, Smith pointed out.

In June 2011, an officer in Page, Ariz. had his body camera on when he fatally shot a 50-year-old domestic violence suspect during an incident. Based on evidence from the video, the officer was cleared of wrongdoing in court, according to multiple reports.

Smith said he looks forward to coming up with fair and legal guidelines for usage, so that cameras will be an effective policing tool for Gilroy.

“We’re still beta testing them. We’ll see how they go, then the POA will make more of a determination and bring it to administration,” he said. “Our administration works with us reasonably. They’ve always been reasonable, we’ve always had open discussions and it’s never been an issue working through things.”

Gallacinao said the testing and negotiating phase should resolve in a few months.

“There are members in the POA who see value in the program as the department does, so we expect that this will be resolved in the immediate future,” he said.

Gilroy Councilman and attorney Perry Woodward said body cameras offer an simple aid in “getting to the truth of what happens on the street,” and given how lightweight and inexpensive they are today, it would be “irresponsible” for a department not to use them.

“Although a camera won’t solve all the problems and there will still be plenty left for folks to argue, a camera protects both ways, it protects both the officers from unfair accusations and the public from over-zealous law enforcement,” Woodward said.

Battery life: Four hours. (When used activated during stops only, the device will last though a 10-hour shift).

Recording time: Four hours.

Weight: 3.5 ounces, about the weight of a deck of cards

Size: A cell phone or pager.