Gilroy

– Jim Laizure doesn’t waste words. A cigarette perched on his

lips, he speaks with spare frankness, especially when it comes to

himself.

Gilroy – Jim Laizure doesn’t waste words. A cigarette perched on his lips, he speaks with spare frankness, especially when it comes to himself.

He doesn’t enumerate the countless ways he revamped Gilroy’s police force during his 20 years as police chief – Gilroy’s first official chief. He doesn’t describe how he standardized its uniforms, established the 911 system, secured a radio frequency, penned its first manual, planned the Rosanna Street station, and even started up the cadet program, which reared today’s chief, Gregg Giusiana. He doesn’t talk up an award from then-governor Ronald Reagan, or his stunning array of sharp-shooting honors, displayed on a burlap banner in his garage.

Instead, he wants to talk about welding, or the Mariposa mountains, or what makes a good cop. Or his wife Betty, her wit undimmed by multiple sclerosis, still cracking wicked jokes from her bed.

“She’s the real story,” he says, taking a deep drag on his cigarette.

Fortunately, plenty of people want to talk about C.J. “Jim” Laizure, and now, they have a chance. Twenty-six years after his wistful retirement, Laizure’s name is emblazoned on the department’s new Seventh Street headquarters, and his name is on everyone’s lips – even those who knew him just briefly.

“I still think about him,” said Chuck Ellevan, a retired Gilroy police sergeant, hired by Laizure in the late 1970s. “I try not to owe much to anyone, but if there’s anybody that I owe anything to, it would be him.”

A hands-on chief, Right down to the bullets he made

Stationed in his musty garage amid wrenches and ironwork, Laizure still exudes a calm command. Officers such as Ellevan call him “a cop’s cop,” and “a cop’s chief,” with a war-weathered face that goes boyish when he cracks a smile. When he hired a new recruit, recalled Police Chief Gregg Giusiana, he’d look them over, then pronounce, “Well, I guess we’ll give you a try.”

Around town, you wouldn’t know he was the police chief, said Steve Ashford, whose father knew Laizure through the Kiwanis Club. Laizure’s kids were instructed to describe him only as “a city employee,” and if questioned further, to say he was a policeman, said Lynn Laizure-Noto, the oldest of his four children. When car accidents happened, Laizure rushed to the scene to direct traffic; when Gilroy officers were spit on at student anti-war protests in San Francisco, the chief was there with them.

“I didn’t ask any officer to do what I wouldn’t do,” Laizure said. Sometimes, that drew criticism from city officials, who worried that he put himself in danger. His response: ” ‘How can I train them if I don’t know what’s going on?’ ”

“For him, the officers came first,” said GPD retiree Doyle Stubblefield. “He’d walk the streets with us. He’d always commend you for doing a good job.”

He was a hands-on chief – literally. At home, he welded filing systems to alphabetize police cases, and crafted his own bullets for target practice. As a child, Laizure-Noto recalled, she watched her father melt down the silver and stuff the casings with lead; after he’d fired the rounds, she scurried around the range to retrieve the spent bullets for recycling.

More than once, said DeLeon, school groups touring the station saw Laizure stroll in, dressed in grease-stained coveralls, after working on one of his beloved “heaps”: broken-down cars he fixed up, sometimes fitting them with U.S. flags or fierce steel teeth. One such “heap” gave out on a winding road in the Mariposa Mountains, where Laizure went camping, recalled son-in-law Benjie Noto, leaving Laizure and Noto careening toward a cliff. “I’m not jumping ’til you jump!” Laizure yelled, according to Noto. Just before the car flipped, the two bailed.

Even with stories like that, said Noto, “I always felt safe with him. In the mountains. Anywhere.”

A no-nonsense guy with ideas – and a lot of heart

As chief, he was authoritative, not authoritarian; firm, yet approachable. When called upon to support Gilroy’s first domestic violence shelter, he embraced the idea, and rapidly fired off a letter in support, recounted Lupe Arrellano, the first manager of La Isla Pacifica.

“He was a no-nonsense guy, and he had a rough side to him,” said Arrellano. “But when people called, he embraced their concerns.”

That care extended to his own officers. When retired officer Pat DeLeon witnessed Gilroy’s first double-fatality, Laizure talked him through the trauma.

“He said, ‘This is the first of many you’ll experience,’ ” DeLeon said. “And, ‘My door is always open.’ ”

Years earlier, when a girl named Betty met Jim Laizure at a Merced roller-rink, long before he became Gilroy’s chief, she noticed that he was attentive to the kids, “not the babes.” That drew her to him, despite the snide remarks he tossed her direction. If he didn’t pay much attention to the babes, he made an exception for her.

“She used to have black-and-blue knees … she fell on them so much, they were always bruised,” Jim Laizure recalled. “Her being a pretty good-looking gal, I wanted to get better-acquainted.”

“Yes – that’s where I met that hunk,” Betty Laizure replied haltingly, her voice pared down by her illness. MS has hollowed her cheeks, but her chin and profile remain regal, her repartee quick. Sgt. John Sheedy, a longtime family friend, has dubbed Betty “the brains of the operation.” When then-mayor Sig Sanchez traveled to Merced to interview Laizure for the top police job in Gilroy, he joked, Betty impressed him even more than Jim did.

“I always told Jim that she got the job for him,” Sanchez said. Still, “you could see that he was aggressive, and he had ideas.”

When Betty first met him, she sized him up somewhat differently.

“She thought I was a smart-aleck,” Jim said.

“That’s true,” replied Betty. “In retrospect, I probably took it the wrong way.”

An old-fashioned guy who was ahead of his time

As chief, Laizure was old-fashioned in the best sense of the term, Ashford said. Small crimes mattered to him, and the everyday problems of Gilroy’s people were his own. Yet he dramatically modernized the department as chief, introducing standard uniforms, badges, policies and procedures, listed in a 200-page manual that took Laizure four months to write. Almost every night, the chief took his typewriter home, logging 16-hour days to get the work done.

“It wasn’t an 8-to-5 job,” he said mildly.

Under his guidance, the pint-sized department gained a big reputation. Gilroy was the fourth city in California to operate a 911 system, and one of the first to employ cadets. Laizure testified before state legislators to expand officers’ training requirements, and to reimburse police agencies for training costs. He helped found the Central Coast Counties Police Academy and the countywide Avoid the 13 program, which targets drunken drivers.

“He was way ahead of his time, in terms of technology,” said Detective Frank Bozzo, the department’s historian and the last officer Laizure ever hired. “He set the foundation for the department we have now.”

Yet as the department pushed forward, some officers became frustrated with Laizure, who they saw as old-fashioned, in a bad sense. Some officers pushed for new equipment on par with San Jose, and Laizure resisted. In 1980, a bitterly-split police union gathered at the old Fifth Street firehouse, and narrowly passed a no-confidence vote. As a newcomer, Ellevan chose to abstain; DeLeon likewise refused to vote, and left the department not long afterward.

Disheartened, Laizure retired. When he stepped down, he ended a 20-year tenure: to this day, he is the longest-sitting police chief in Gilroy’s history.

“It just devastated him to the core,” said Lynn Laizure-Noto. “It was awful.”

Even today, the union’s vote still smarts. Some officers later apologized to the family, Laizure-Noto said; others never have. But for Laizure, there is some solace in the union’s decision, 27 years later, to dedicate their new headquarters to the chief.

“To me,” he said, “it kind of made up for the stuff that had happened before.”

Devotion to his wife outlasts illness

Betty Laizure spent many nights alone, as her husband slaved over department projects, and when emergencies called him from their Gilroy home. She handled the hassles with spunk, Laizure-Noto said. One night, when torrential rains flooded the city, Jim Laizure came home to find Betty and the four kids bored silly in a cold and darkened house, roasting beans on toothpicks over a candle. Laizure cracked up, and the kids did, too.

“He was tired, he was wet, he was hungry – but that scene really lifted his spirits,” Laizure-Noto said. “Roasting these stupid beans! They tasted utterly awful!”

But Betty Laizure had already weathered far worse, having seen Jim off to Korea, where he piloted a B-50 bomber, and uprooted from Merced, where they had made their family. When the Laizures relocated to Gilroy, Jim Laizure recalled, “Betty said that wherever I went, she would go. She’s always taken that attitude.”

And he, in turn, has stood by her. In her 30s, Betty was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, then a mystery disease. As the decades progressed, the illness confined her first to a wheelchair, then to her bed. Laizure, who opened a welding shop after retiring from the PD, quit working entirely to care for her.

“The guy has always impressed me, as a man,” said Ellevan. “Not everyone would do that.”

His devotion materialized in wooden chests and tables, now stationed around their Carmel Street home. As kids, Laizure-Noto and her siblings once spent hours sanding a homemade wooden dresser, their father’s gift to their mother. Every now and then, Jim Laizure would run his fingers along the top, saying, “Feel that, it feels like glass.” Then he’d joke: “Not smooth enough!” and the kids would go back to sanding.

“She might be the one in the bed,” Laizure-Noto said, “but it’s a two-way street.”

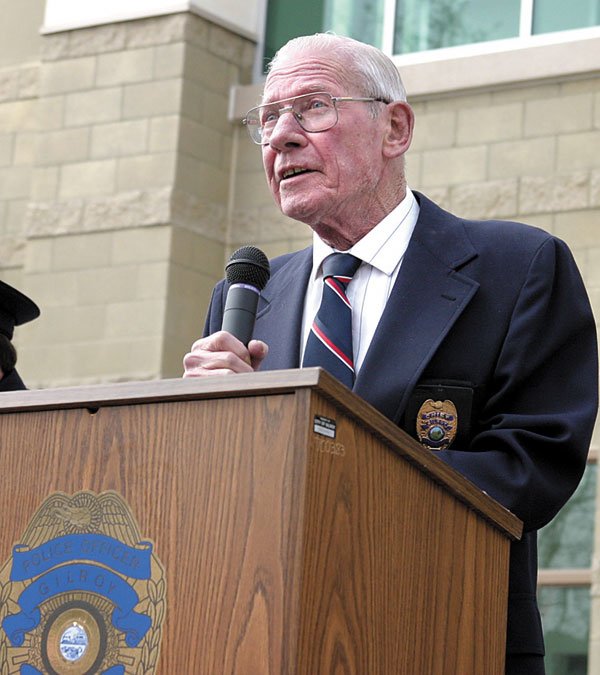

When the police dedicated the new building to Laizure, in a packed Saturday ceremony, Betty Laizure couldn’t come. Instead, the ceremonies were captured for her on videotape by city employees. When Betty pops the tape into the VCR, she’ll see her husband, trim in a dark suit, humbly addressing hundreds before the building he’s dubbed ‘Fort Laizure’, the new station that bears his name.

He says a few words of thanks, peers up at his own name and pronounces, “A wise old gentleman once told me, if you’re standing up in front of a group and don’t have anything to say, just shut up and sit down.” He surveys the chuckling crowd. “That’s great, great advice,” he remarks, and sits down.