County awaits re-submittal of application before public outreach

to those living west of Gilroy

A quarry in their backyard means Toni Crane won’t be able to train her dressage horses anymore, and her husband Bob, an emergency surgeon, will surely have trouble sleeping through the incessant grinding and hauling of gravel all day.

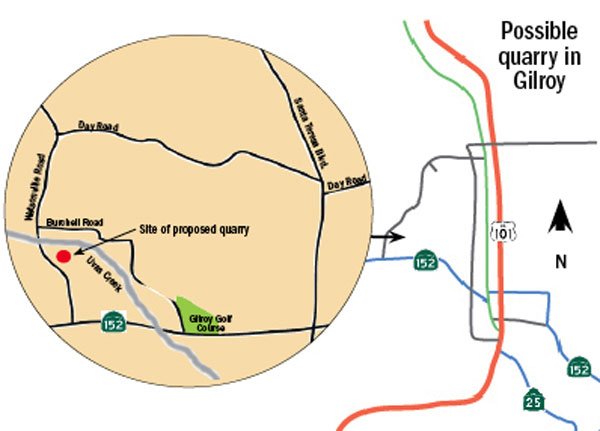

The couple who lives at the corner of Burchell and Watsonville roads is not alone. Denizens throughout the residential cluster west of Gilroy have a host of problems with a 40-foot deep, 32-acre pit behind their properties along Uvas Creek. They have even started an online group to vent concerns about how a rock-crushing haven would affect their property values, pollution, traffic, and the general peace and quiet they’re used to.

“I’m not an extreme environmentalist, but I like to protect nature and keep it pristine, and I do know that coming in and trying to put in a mining site here has is got to bring some destruction,” said Nathan Miller, a resident along Burchell Road. “Take it somewhere else, not in someone’s neighborhood for God’s sake.”

The raw materials supplier behind the project could not be reached for comment, and the county’s senior planner working on the application, Gary Rudholm, did not return messages for comment. But county assessor’s documents show two agricultural properties along Watsonville Road with a collective area of 135 acres and a joint value of about $3.6 million, and this is where the mine and processing facility could go. The land is currently zoned as agricultural combined district, according to county documents, and a mining operation is allowed, according to a conversation Bob Crane said he had with Rudholm.

The county declared the quarry application, initially filed April 14, 2006, incomplete last summer, though, because Rudholm expressed environmental concerns, according to residents who met with Rudholm last week. Rudholm told them the city of Gilroy also has expressed concern about impacts on traffic and roads, but nobody at the city could confirm this and others did not return calls for comment. Still, Watsonville Road and Highway 152 are two-lane roads unaccustomed to 10,000 industrial trucks a year hauling gravel away each work day at a rate of nearly one every 15 minutes, according to county figures and one resident’s calculations.

Toni Crane first heard about the quarry a couple of weeks ago after her horses started acting nervously: Her husband went to check out the property and found two surveyors nearby who said they were taking measurements for a potential quarry, according to Toni Crane.

“It’s dangerous to ride my horses in a loud and noisy environment,” Toni Crane said. “I’m not sure I could stay here with a quarry next door because it might not be safe to do what I do here. I mean, my horses were on alert just from two people, so a quarry that’s grinding rock and loading trucks, you know, that’s not going to be an impact we’ll enjoy.”

The Cranes were also thinking about remodeling their 38-year-old home, but Toni Crane said she was not so sure anymore because that “would be like investing in a sinking ship.” Miller added that he was also concerned about run-off water finding its way into the creek and ultimately the area well.

Before it comes out of the faucet, though, the water also serves as the life blood for the steelhead trout, an endangered species that Herman Garcia has been trying to save as the president of the nonprofit Coastal Habitat Education and Environmental Restoration. Miller called Garcia when he heard about the quarry project, he said, and Garcia said he is fighting the application with the blessings of state and federal environmental authorities.

When the application comes back online, the county will then contact surrounding property owners to take part in a public meeting required for an environmental report that the applicant will pay for. And if the quarry does come to town, perhaps when it’s done generating 1.7 million cubic yards of gravel that it crushed, sorted and stock piled on site, the area could become a recreational or agricultural lake, according to figures residents obtained from the county.

“Maybe a lake would be nice,” Miller said, “but it’s kind of nice how it is. Let’s just leave it alone.”

About the quarry:

32 acre pit proposed

40 feet deep

10,000 trucks hauling gravel each year

One truck driving through every 15 minutes