On a crowded November ballot, sharing space with a county transportation sales tax measure and a state proposition to legalize marijuana for adult recreational use, is Measure H, the official name for the Urban Growth Boundary Initiative, which would limit how big and how fast the city of Gilroy can grow.

Two weeks ago, over a luncheon of stuffed mushrooms and pesto pasta, community leaders in the Gilroy Rotary Club heard how the growth boundary, which would last through 2040, might impact business and the regional housing supply crisis, should it pass.

Speakers from the anti-sprawl group Gilroy Growing Smarter (GGS), which qualified the measure for the ballot after leading a successful petition drive, debated the topic with leaders of the Gilroy Chamber of Commerce and Gilroy Economic Development Corporation, who were early critics of the proposal.

How it works

During opening comments, Carolyn Tognetti, of GGS described an urban growth boundary as “just a line drawn around the city and approved by the voters.”

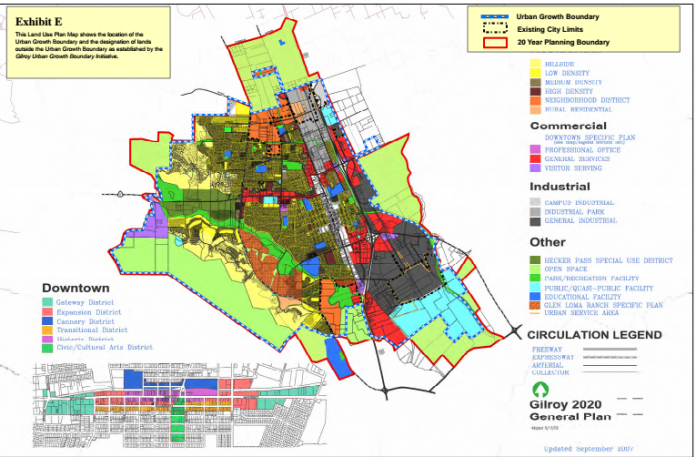

If passed, the boundary would determine where the city could and could not grow, and any redesignation of lands or amending of the boundary, before Dec. 30, 2040, could only be done by a vote of the people or by council action in limited situations, such as to comply with state affordable housing laws.

Outside the UGB, which the group says was drawn using input from last year’s General Plan 2040 workshops and committee meetings, lands would be classified as “open space” and “agriculture,” not for urban development.

Exemptions could be made for certain projects, such as schools, parks, water and sewer facilities, and the aforementioned affordable housing, should the city make certain findings. For example, if the land in question is right next to the UGB and there is no suitable land within the boundary for the proposed purpose, a public hearing would be held on the matter.

Measure H would also allow 50 acres a year to be brought inside the UGB or land within the boundary redesignated general industrial—there is no separate allowance for commercial development—but only if the city makes certain findings, a process Tammy Brownlow, president of the Gilroy Economic Development Corporation, would characterize as “onerous.”

Later, Brownlow said, “There is also a requirement that there be a pending application for a specific development. That is unlikely to happen as the current process without the UGB can take up to two years. If a proposal is outside the UGB you can add another year, assuming LAFCO approves, which is always unlikely. No company will enter into this lengthy and uncertain process.”

At the debate, Tognetti said the anti-sprawl measure is not a “no-growth plan.” She said it would refocus Gilroy on “city center growth” and allow for 8,000 housing units over its lifetime.

Job impacts

During her opening statement for the opposing side, Brownlow, said with the UGB in place, the city would not be able to achieve a “jobs-housing-balance.”

Citing findings from a city-funded independent report on UGB impacts—known as the 9212 report—Brownlow said there would be a loss of 45 percent in potential jobs, if the measure were implemented under the adopted 2020 general plan (under the draft 2040 general plan, the estimated loss of potential jobs would drop to 14 percent, according to the same report).

Additionally, she said: “The jobs created by infill development would not be the type of jobs that we hope to attract to Gilroy—living wage, full-time jobs with benefits in areas other than retail and service sectors.”

Brownlow said that, in her role, she believed the amount of land for projects—like a UNFI, which is 45-acres—to be very limited, as she fields requests for property every day. She also currently has three available sites that are more than 20 acres, in addition to a project in process that would develop a 30-acre site.

Cognetti argued that 2040 general plan consultants and city staff projected that Gilroy will attract 10,000 new jobs in the next 20 years and that even if projections are doubled, there is plenty of room for new jobs.

Brownlow found that argument problematic. “The proponents look to the analysis completed three years ago when the background reports were being completed for the 2040 general plan. That analysis is based on historic absorption rates,” she later explained. “Our current absorption is significantly more than over the past 20 years. Look around our industrial areas—when can you recall 80 acres being developed in a two- to three-year time frame? These projects are creating the jobs we have desired for many years.”

Good for business?

David Lima, secretary of GGS, said the measure is “designed to allow for normal growth and prosperity” and that there was sufficient land within the boundary for commercial development. This is “not a job killer,” he said. The measure would allow for “business as usual.” Sprawl—residential growth and the new businesses that serve them, he argued, take away from downtown and more beneficial infill development.

“With limited population growth is fewer potential customers for existing businesses,” said Mark Turner, president/CEO of the Gilroy Chamber of Commerce. “Those of you who have businesses in town know that you need new customers in order to keep your business growing and sustain that business.”

What about roads?

Citing the 9212 report, which stated that due to potential job numbers decreasing relative to the population, the number of vehicle miles traveled for the city would slightly increase, Turner argued that the additional commuter miles would add wear and tear on the city’s roads.

This would lead to, he said, “more congestion, slower commute times, and frankly, greater frustration.”

According to the 9212 report, under the 2020 general plan and draft 2040 general plan scenarios with the urban growth boundary in place, the amount of land available for residential development would decrease by 640 acres and 450 acres, respectively, leading to a decrease of 2,929 and 4,344 potential housing units.

Tognetti argued that with less sprawl, there would be fewer cars on the road.

The report continues: “With the initiative, the number of roadway extensions or improvements that would be needed outside of the proposed UGB would be reduced” under both general plan scenarios. Traffic impacts would also be negligible: “Traffic volumes on the freeway would decrease slightly on some segments and increase slightly on others.”

Let’s all live here

The greater Bay Area, of which Gilroy and Santa Clara County are a part, is experiencing an ongoing housing supply crisis. According to a report by the San Francisco Chronicle earlier this year, the nine-county region needs to almost double the amount of building permits it issues from its current 27,000 annually to meet pent-up demand.

To help streamline the building approval process, Gov. Jerry Brown has recently put forward a proposal that would make it easier for eligible multifamily housing projects to get off the ground if they adhere to local zoning laws and include affordable housing.

Measure H, under both general plan scenarios, would decrease the number of acres available for housing, which is its overall intent, according to Gilroy Growing Smarter.

Still questioning?

In this article we have explored a couple of the primary arguments for and against Measure H, as expressed by the measure’s proponents and two local business groups that oppose it.

Next, we will draw in opinions, analysis and debate from regional experts on all sides of the issue as we get closer to election day.

What do you want to know about the biggest growth decision in Gilroy’s recent history? Post your questions on our Facebook page, or leave us comments at the bottom of this story on our website at www.gilroydispatch.com.