It’s no surprise to those who read Gilroy’s police blotter or

scan the weekly Most Wanted: Nearly 80 percent of Gilroy’s adult

arrestees are Latino. The question is why.

Gilroy – It’s no surprise to those who read Gilroy’s police blotter or scan the weekly Most Wanted: Nearly 80 percent of Gilroy’s adult arrestees are Latino.

The question is why.

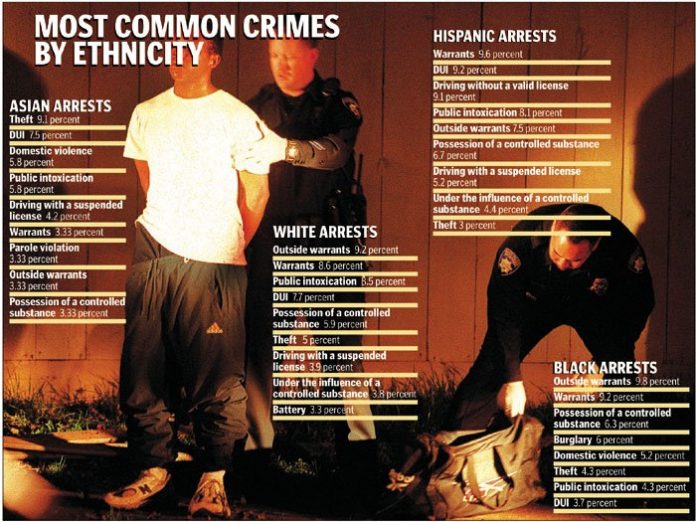

Gilroy’s numbers mirror state and national statistics, which show that Latinos are over-represented in the criminal justice system. Census figures are slightly stale: Gilroy was last counted in 2000, when 54 percent of the city’s residents identified themselves as Hispanic and 59 percent were white. (Hispanics are counted as a separate, non-racial group in the census, which means respondents can count themselves as both Hispanic and another race.) Though Gilroy is a majority-Latino city, demographics alone don’t account for the statistics, wrote Police Chief Gregg Giusiana.

The numbers don’t add up to officer bias either, he cautioned.

“It would be easy to jump to the conclusion … that ethnicity influences the [officer’s] decision to arrest,” but Gilroy police don’t discriminate, Giusiana wrote in response to a Dispatch interview request. “The reasons [for Hispanic overrepresentation] … are varied and complex.”

Income and gangs impact

crime rates

Economics factor into crime rates, said Steve Smith, head of the Administration of Justice Department at Gavilan College, particularly drug and alcohol abuse, which Smith described as a form of “self-medication” for some low-income workers who can’t afford prescription pain relievers. Drug-related charges such as driving under the influence and public intoxication make up at least 28 percent of Hispanic arrests in Gilroy, and fuel other crimes, such as theft and domestic violence.

“If you ask me, drugs are involved in 90 percent of crimes,” said Smith, “and I include alcohol.”

But drugs factor into roughly the same percentage of crimes committed by whites in Gilroy, noted Peter Arellano, the city’s only Latino city councilman, and are unlikely to account entirely for the difference.

Gilroy’s mostly-Hispanic gangs have also pushed Hispanic arrest rates higher, Giusiana wrote. The city’s gang wars pit U.S.-born Norteños against immigrant Sureños. Their victims are most often other Hispanics, Smith noted. Income impacts gangs, too: Low-income parents are likely to work longer hours and have fewer after-school options for their kids, Smith said. Gangs fill that void, recruiting young teens and intimidating those who don’t choose sides, Smith explained.

“It’s turned into this monster on the streets,” said Carlos Flores, a case manager in Community Solutions’ Restorative Justice Program. “It’s like a cancer, eating our communities.”

A few crimes are more frequent among Gilroy’s Hispanics than among other ethnic groups: Driving without a valid license is the second-most common charge among Hispanic arrestees, making up 9 percent of arrests. The same charge makes up less than 1 percent of white arrests, 1.1 percent of black arrests, and 2.5 percent of Asian arrests. Undocumented immigrant drivers who can’t get licenses may be one factor, but it’s difficult to track: GPD crime analyst Phyllis Ward said country-of-birth, which is recorded on inmate booking sheets, is not logged in computerized crime data.

Solutions lie outside

law enforcement

The frequency of Hispanic arrests shocked Flores, who grew up in Gilroy. As a youth organizer, Flores says he’s observed that Hispanic/Latino youth are more often stopped by police, and said police presence is more significant on the city’s lower-income east side. Arellano echoed his words, recounting being stopped by Gilroy police as a teen, while driving his father’s brand-new car.

“Does it still go on? Yeah, I hear that it still goes on,” he said. “I don’t think it’s the whole answer – it’s multifactorial. It’s economic. It’s educational. But obviously, there’s some profiling being done.”

Giusiana said officers do not use ethnicity as a basis for arrests, and wrote that police “do a considerable amount of outreach into the neighborhoods, especially the lower-income areas of the city, to make a connection with them.” Other programs the chief touted include truancy abatement, aimed at keeping kids in school and out of trouble, and the Anti-Crime Team’s intervention officer. To reduce crime before it starts, hands-on community policing is key, said Smith.

“You’ve got to get cops out of their cars,” he said. “Cars are cocoons … In them, an officer’s just a guy in an air-conditioned Crown Victoria with expensive sunglasses.”

Still, cutting crime in minority communities is a job too big for police alone, whose primary role is to enforce the law, said Smith. Giusiana agreed, touting nonpolice efforts such as the Gilroy Youth Center and Fresh Lifelines for Youth (FLY), a program which teaches Mt. Madonna High School students about their rights and responsibilities in the justice system.

“We do not have the staff or the expertise to address these complex social issues,” the chief wrote.

Arellano agreed.

“No. 1 for me is prevention,” he said. “We can put 2.5 policemen per 1,000 on the beat, but we’ll just create a police state – and we’ll still have the criminals coming out.”

Flores was frustrated by what he called a lack of intervention services to prevent Hispanic youth from drug abuse and crime. He applauded the work of the Youth Center and Victory Outreach, a Christian ministry Flores said reaches teens on the street. FLY has also made an impact: After completing the program, 90 percent of teens say they’re less likely to break the law, said Aila Malik, director of law programs at FLY.

“That’s how we’re hoping to effect change,” said Malik. “One by one, with these kids.”

As he scanned the numbers, Flores said much more remains to be done.

“It’s the same issue with our community over and over again,” he concluded. “A lot of people want to point fingers – it’s drugs, it’s alcohol, it’s gangs. But what are we going to do to stop it?”