Santa Clara County

– Hundreds of county homeowners are saving thousands annually

thanks to a property tax break they may not deserve.

The tax break

– a benefit of a state law that aims to protect farm land and

open space – is being enjoyed by many who own million-dollar homes

in the country, residents who don’t farm but live in subdivisions

that were once sprawling ranch lands and are now rural residential

neighborhoods.

Santa Clara County – Hundreds of county homeowners are saving thousands annually thanks to a property tax break they may not deserve.

The tax break – a benefit of a state law that aims to protect farm land and open space – is being enjoyed by many who own million-dollar homes in the country, residents who don’t farm but live in subdivisions that were once sprawling ranch lands and are now rural residential neighborhoods. The parcels are generally far below the law’s minimum size requirement of, in most cases, 40 acres.

Some homeowners save as much as $5,000 annually, and many more residents receive breaks ranging between 20 and 40 percent of their annual tax bill.

“There’s no question that there’s substantial abuse of the Williamson Act provisions,” Santa Clara County Assessor Larry Stone said of the 1965 law that created the tax break. “The purpose of the act is not to provide a tax break for rural homeowners.”

Stone’s office has no idea how much revenue the county loses each year to the tax break, and despite two directives from the state to purge non-compliant properties from the Williamson Act, the county still hasn’t done so.

“It’s out of control, I see it every day,” said John Gormley, a Realtor who owns 20 acres under Williamson on Finley Ridge in east Morgan Hill. “I think [the planning office] needs to go out and recheck. They should be out if they can’t meet any of the aspects of the Williamson Act.

The amount of tax savings depends on a number of factors, including the purchase price and the length of time an owner has held a property. Size matters because the single acre on which the house sits is taxed at the standard rate.

Jason and Daniella Ross, who own a home on 2.2 acres on Furlong Avenue, saved about $80 last year. Martin Bress and his wife Rhoda, a Gilroy Unified School District Board member, bought a house on 9.8 acres on Fitzgerald Avenue in 1992. They saved more than $3,000 on their last tax bill.

Gormley said he saved about $4,000 last year on his property, which is one of 38 parcels of about 20 acres each that comprise 700 acres of grazing land on the steep hills above Anderson Lake. Gormley and his neighbors are facing eviction from the act.

County planning officials say they don’t know how many of the county’s 3,000 Williamson parcels are out of compliance, but hundreds of them are not being farmed. The law requires that lots of prime, or valley-floor, farm land be at least 10 acres, and that non-prime parcels be at least 40 acres. There are 900 Williamson parcels of fewer than 10 acres and about 1,600 of fewer than 40. All but 11,396 acres of the 330,769 under contract are non-prime.

Most county contracts date to the late 1960s and early 1970s. The contracts attach to the land. They require a 10-year commitment that automatically renews every year, and are not easily terminated. Either the county or the contract holder can non-renew and be free of the contract after a decade, and in limited circumstances, a land owner can cancel a contract and pay a penalty of 12.5 percent of the land’s value. A 2003 law assessed a 25 percent penalty on owners who develop the land illegally.

If Gormley’s property is non-renewed, his property tax would double over the next 10 years. He said the Finley Ridge properties should remain in the act because they meet the spirit of the law, and that the county needs to abide by the contracts it signed.

“We deserve it because they allowed it,” he said. “You can’t graze it all year, but in the summer it’s prime grazing land. It’s all grass, nobody up there is out of bounds.”

Unlike, he said, some residents in San Martin Estates, who have built palatial homes, and in a nod to agriculture, planted a small vineyard.

“Do you know why they do that?” Gormley asked. “Because they can. Because they can afford to.”

One of the largest homes in the county, more than 16,000 square feet, is currently under construction on W. San Martin Avenue. Last year, it owners, Dale and Anne Shipley, received a tax break of about $5,020, though that figure will be less when their house is finished.

Rhoda Bress and the Shipleys declined to comment for this story.

One of their neighbors, San Jose employment attorney Steven Cohn, whose land is now out of the act, said the tax savings are negligible to most people in that neighborhood. He said he didn’t know about the act when he bought his house in 1997.

“We were just dumb consumers who wanted to have a nice big home in open space,” said Cohn, who owns 12 acres and saved about $3,700 last year. “[The tax break] is a drop in the bucket.”

Cohn said he’d be surprised if his neighbors protest if they’re evicted from the act.

“I think they’ll shrug their shoulders,” Cohn said. “There are a few people grazing cattle, but I don’t think the others will care.”

But Theresia Sandhu, who with her husband Daljeet, owns a bare 20-acre lot in the area, said they won’t be able to hold on to the land if they lose the tax break. The Sandhus bought the land in 1988 for $275,000. With a standard assessment, their 2004-05 tax bill would have been about $4,700. Under Williamson, the couple paid only $125.

“We can’t afford that, we would have to sell it off,” Sandhu said about the possibility of losing the contract. “We were told that we would pay extra low taxes if we kept the land pristine. It’s our dream for retirement to live up there.”

In 2002, the county was sharply criticized by the California Department of Conservation, which enforces the act, for not properly managing its Williamson contracts. Earlier this month, the agency recommended for the second time that the county non-renew contracts for parcels that don’t meet minimum size requirements.

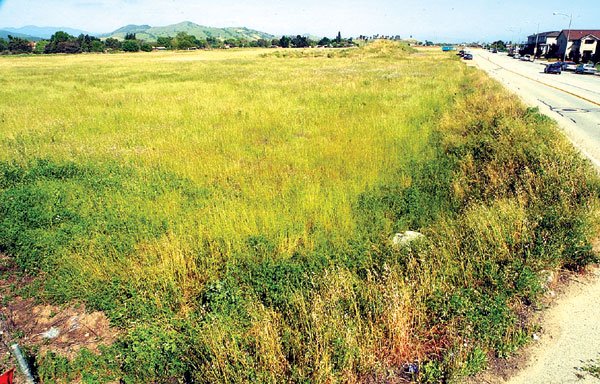

In the 1970s and 1980s, county planners allowed numerous subdivisions of sprawling ranch land into rural residential home sites. An 870-acre parcel in west San Martin was chopped into more than 40 separate parcels and became San Martin Estates. East of Gilroy, more than 230 acres were divided into home sites and became Golden Heights. Agriculture started to vanish, but the tax break stayed in place.

Ultimately, it’s up to county supervisors to determine which contracts the planning department does not renew. Interim Planning Director Mike Lopez said this week that it may be a staggered process, with only the smallest parcels non-renewed at first. Any property owner who receives a notice of non-renewal will have the option of defending his contract.

“It’s important to achieve compliance with the Williamson Act and the purposes it was meant to achieve,” Lopez said. “Size is an important factor. If you’re not big enough, you shouldn’t get a tax break unless you can demonstrate that you have agriculture.”