GILROY

– When it comes to fighting unwanted invasive plants in

California’s parks and rangelands, horse apples can sometimes be

bad apples.

And forget crying over spilled milk

– park rangers shed their tears over spilled oats and alfalfa

instead.

GILROY – When it comes to fighting unwanted invasive plants in California’s parks and rangelands, horse apples can sometimes be bad apples.

And forget crying over spilled milk – park rangers shed their tears over spilled oats and alfalfa instead.

So along with beef and chicken, the government has added something new to the list of products scrutinized by inspectors: animal feed.

That’s because they say both manure and spilled hay left by horses and cattle can help sustain – if not increase – populations of invasive and noxious weeds, crowding out their more desirable native brethren.

To combat the problem, the federal government is demanding that equestrians help with prevention by using a new product when they ride on federal lands: feed that’s inspected and certified as free of certain weeds.

And those regulations are creating a fledgling niche industry in Santa Clara County, where – thanks to the foresight of growers and the county’s agriculture department, four of the 11 weed-free hay producers found on a statewide Internet directory ply their craft here.

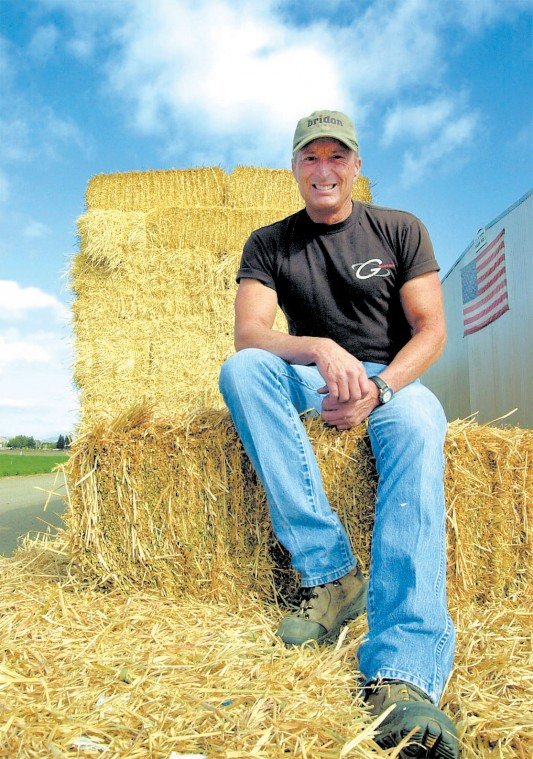

“We’re the trend-setters and not the trend-follower,” said Kip Brundage, a Gilroy hay farmer and president of the county’s Farm Bureau who grows certified hay as part of his product.

By next April, would-be federal park-goers will be turned away at the gate if they don’t have state-certified weed-free hay in their nose bags – or be subject to up to six months in jail or a $1,000 fine if caught cheating.

Ranchers on federal lands will also be subject to the provisions, which are designed to help control and eradicate up to 200 different noxious, invasive and non-native species of grasses and plants.

Major pests on that list include yellow star thistle, Medusa head, morning glory, Johnson grass, poison hemlock, quick grass and bull thistle.

While the county may lack federal lands close-by, officials at Henry Coe State Park are considering the new provisions. Invasive plants are an ongoing, significant concern at the massive old ranch, and park rangers are already installing signs asking horseback riders to rake up manure or loose hay that could exacerbate the problem, said Kay Robinson, the park’s superintendent.

Officials currently use a four-pronged approach of chemicals, insects, occasional prescribed burns and good old manual labor to battle the yellow star thistle that invades open meadows and roadside areas of the park. Robinson said they’re considering a weed-free hay requirement as well and are likely to implement one in the future, although no timeline has been set.

“I think it would help,” she said. “Our problem now is the existing fields of thistle, but whatever we can help not to bring in the park in the future just helps us combat that problem now.”

County parks don’t have a policy and aren’t currently considering one, but do encourage the use of weed-free hay, said spokeswoman Tamara Clark-Shear.

“It’s probably something we’ll begin to talk about as another method to manage invasive weeds,” she said.

With the regulations coming down the pipe from the federal government, the county agriculture commissioner’s office established its own inspection program two years ago.

To earn certified status for their hay, growers open the borders of their fields to inspection by their county agriculture commissioner roughly a week before harvest. When harvested, it has to be removed in 10 days and put in a secure place separate from traditional hay. Each bale then comes with a certificate.

Added costs along the way include inspection fees, increased pesticide spraying, separate storage, decontamination of equipment between fields and even special twine to bale the hay.

The major difference in growing is a requirement for increased awareness, said Bill Throgmorton, a retired veterinarian who grows hay as a hobby in Gilroy. But the disadvantage is recordkeeping.

Growers have to maintain records for two years on every bale of certified hay sold, in case government officials have questions later while dealing with a suspected cheater.

“You may have 75 customers over a given time, and you have to keep track of each one,” Throgmorton said.

Pesticide application can also be a problem, Brundage said, because different chemicals are needed for different weeds.

“What kills broadleaf doesn’t control grasses,” he said.

Those costs are passed along to the consumer in the form of prices 50 percent higher than standard hay. Depending on factors such as quality and volume, Brundage will sell a bale of certified alfalfa for $11 to $14, more than the $9 he’s likely to charge for a standard bale.

“It’s going to cost more, until some water is under the bridge and (growers) have experience under their belts before the price settles down,” he said.

Many hay farmers don’t want to get involved, Brundage said, because it can be too much of a hassle to grow.

Throgmorton thinks the new regulations are a good idea, but noted that the program could be even better by targeting animal health as more of a priority. While some weeds on the banned list can damage horses’ digestive systems, so do some that are legal in the hay because they aren’t propagative or invasive.

“It has its weaknesses in terms of animal health,” he said. “I’d like to see something that assures quality for the horse.”

Horsemen are generally supportive of the program, Throgmorton said. Bob Mason, a Gilroy horseman, saw no real difficulty.

“It’s mainly to keep toxic weeds out of parks, so I think it’s a good idea,” he said.

But Throgmorton said riders will face increased difficulty as laws tighten in the future because of the limited number of producers. In fact, Brundage said that shortage could come as early as next spring – and those needing the certified hay should start stocking up now.

“The consumer will have to do some looking to be able to find it,” he said.

For more information, visit http://pi.cdfa.ca.gov/weed/wff, www.foothill/net/tevis/cwff/cwff.htm and www.weedfreefeed.com on the Internet.