The U.S. Treasury is poised to commit large sums

– perhaps exceeding $100 billion – in its rescue of Fannie Mae

and Freddie Mac, but the real cost to American taxpayers won’t be

known for years.

The U.S. Treasury is poised to commit large sums – perhaps exceeding $100 billion – in its rescue of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, but the real cost to American taxpayers won’t be known for years.

The tab will depend on how Washington runs these mortgage giants and how the housing market and economy perform.

A wide range of outcomes is possible, because the size of Fannie and Freddie is so large. With a $5 trillion book of home loans that they own, or have guaranteed, fractional changes in foreclosure rates can translate into tens of billions very quickly.

In a worst case, the cost could run well above the roughly $125 billion that taxpayers spent in the early 1990s to insure depositors in failed savings-and-loan institutions, some mortgage-market experts say.

In other scenarios the short-term infusion of cash might ultimately be recouped with little or no net cost to taxpayers.

Stocks mostly advanced Monday as investors rushed to lay bets on a recovery in the financial and housing sectors following the weekend announcement that the U.S. government will bail out mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The Dow Jones industrials gained almost 290 points.

If the government hadn’t decided to step in and bail Fannie and Freddie out, it would be more difficult for the average home buyer to get a mortgage at all, said Kent Miller, mortgage broker of 30 years, owner of Monterey Mortgage in Gilroy and former president of the National Association of Mortgage Brokers.

On the flip side, the cost of the government takeover of the two mortgage companies will be passed along to the taxpayers.

“With the government coming in and taking over, any losses that Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac would potentially incur, the government – meaning you and I – gets to pay for the stupidity of everyone else,” Miller said, “in the form of more taxes or less programs.

“But we can’t afford to let the entire U.S. economy go down the tubes.”

Miller predicted that the industry is nearing rock bottom and will see a stabilization in property values when it does.

“If they don’t do it, it will be disastrous,” said David Hart, mortgage broker of 25 years and owner of Gilroy Mortgage, of the government’s decision to back Fannie and Freddie. “I don’t think they have a choice.”

“Without them, we’re really in trouble,” he said of the two giants. “If we don’t do this and there’s no money available to buy homes, the problem of people walking away from their homes will snowball.”

“We need to stop the bleeding right now,” he said. “Hopefully the values will stabilize. I do think this will help. We have to have Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.”

What’s clear is that every U.S. taxpayer is now tethered directly to the troubled housing market. And the stakes are much higher than the $30 billion federal intervention to stave off bankruptcy at Bear Stearns earlier this year.

“This is Bear Stearns times 100 or Bear Stearns times 1,000,” says Brian Battle, a vice president at Performance Trust Capital Partners, an investment firm in Chicago. How much taxpayers lose is “100 percent correlated” with the depth of the housing slump, he adds.

The more home prices fall, the higher foreclosure rates will become and the more losses will pile up at Fannie and Freddie. The less home prices fall, the less that any lender will lose when a loan defaults and the property is resold.

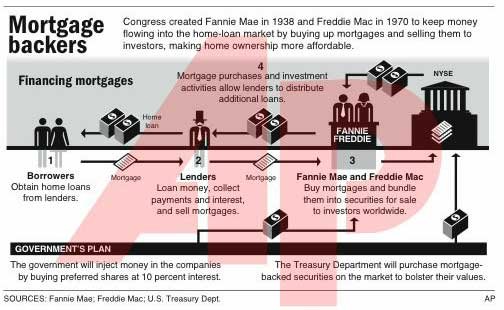

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are known as government-sponsored enterprises, because they were chartered by Congress to create a more stable mortgage market. Over the past year, they have been fulfilling that mission, guaranteeing home loans or buying them outright. Amid a sharp decline in real estate sales and prices, investors have been willing to fund the so-called “conforming” home loans that carry a Fannie or Freddie imprimatur. That has helped keep mortgages relatively available and affordable.

But even though the GSEs were not conduits for the worst “subprime” lending, they are being hit by loan defaults, with Fannie and Freddie posting a combined second-quarter loss of $3 billion.

Their capital, the reserves available to cover future losses and continue funding new loans, fell to the point where the U.S. Treasury Department intervened.

That followed a string of other federal actions in recent months. The Federal Reserve has loaned money to investment banks in addition to the $30 billion in credit it extended to facilitate the buyout of Bear Stearns by JPMorgan Chase.

Bank failures, after a long period of quiet, are rising. The Treasury’s Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. could run through its insurance fund this year and may need additional money from the Treasury to protect insured depositors.

Now the Treasury is becoming an equity investor in Fannie and Freddie and a buyer of their mortgage-backed bonds.

The move is a bid to help restore calm to credit markets, possibly lowering the cost of mortgages and, by extension, helping the housing market recover. The more successful the effort is, the less it will cost taxpayers.

“The Treasury may have to put a couple hundred billion dollars into these (GSEs),” says Christopher Whalen, managing director of Institutional Risk Analytics, a firm that tracks the health of financial institutions.

But beyond the injections of capital to get through the current crisis, he says ongoing operations of Fannie and Freddie should reap profits for the Treasury – thus providing some long-term offset to the bailout’s up-front costs.

“Hopefully the cost to the taxpayer will eventually be zero,” he says. “It might even be positive. But it has to be done right.”

Doing it right, in his view, depends on resolving the long-term structure of the two companies – a politically divisive issue that will be debated by Congress and the next president.

Mr. Whalen suggests that over time, the government should shed the large portfolios of loans that Fannie and Freddie currently hold. The GSEs should focus on their role as a conduit, guaranteeing loans for resale. If the fee for those guarantees is set right, it should be a profitable business – and he suggests that that business be nationalized.

Other finance experts and policymakers argue for other strategies, ranging from privatizing all GSE functions to nationalizing them as much larger entities than Whalen recommends. The Treasury’s new “conservatorship” plan holds the door open to many options, including ultimately returning the companies to their former status as public-private hybrids – but with tighter regulatory supervision.

“In the short term, yes, a bailout’s necessary,” says Joseph Mason, a finance expert at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. “The question becomes, (is it) an opportunity to exit … the current egregious level of government involvement in housing finance?”

Others say the subprime lending debacle is evidence that a strong role for the government in housing finance remains needed. “Private securitization (of mortgages) in secondary markets is what caused this mess” in the real estate market, says Dan Immergluck, a housing expert at Georgia Tech in Atlanta.

Because the GSEs have long been viewed as having implicit federal backing, delaying or avoiding intervention might have added to the ultimate taxpayer tab.

Staff Writer Sara Suddes contributed to this report.